A good rule of thumb, advised Stephen Higgins – founder and managing partner of investment advisory firm Mekong Strategic Partners – is that in developing countries the financial sector will “grow around double nominal GDP growth”. This means that in the Mekong region, where nominal GDP growth is on average 10% per year, there is “some really strong growth in the finance sector”.

One doesn’t have to look too far to see the rise of the banking industry in two of the region’s rising economies: Cambodia and Myanmar. Although perhaps a clichéd comparison, it appears as though Cambodia’s financial sector is today where Thailand’s was ten years ago, and Myanmar’s now where Cambodia’s was a decade ago. This decennium relay race might never be completely accurate, but it does reveal a great deal about the nations’ future trajectory.

Higgins said that the healthiness of the finance industries in each of the Mekong region countries varies quite dramatically. In Laos there is “too much influence by the government-owned banks” and the industry overall is “all a bit sleepy”. Finance in Vietnam has similar problems, but was showing signs of recovery, he said, adding that banking and finance in Thailand is perhaps strongest. “Myanmar’s is coming from a long way behind,” while Cambodia’s finance sector had shown “impressive development, if anything growing too quickly in recent years”.

Bank boom

Indeed, between 2008 and 2013, the number of bank depositors in Cambodia grew from 230,000 to 1.7 million, while borrowing in its robust microfinance sector rose from 800,000 customers to 1.6 million during the same period.

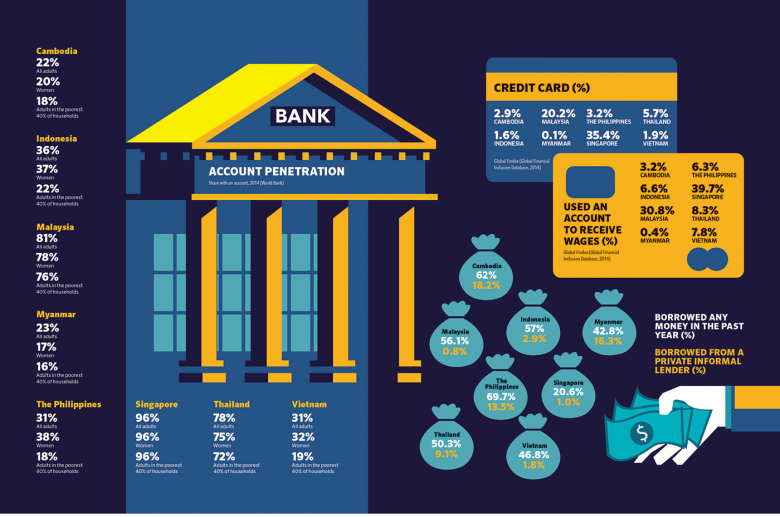

Still, the World Bank estimated that only 22% of Cambodian adults had a bank account in 2014, compared to 78% in Thailand or 98% in Singapore. In Myanmar, 23% of inhabitants possess a bank account – however industry experts note that technologically and educationally, the country’s banking industry remains some years behind Cambodia’s.

“The change [in Myanmar] has been quite significant in all aspects, but this is like the first quarter of a marathon transformation that is likely to last a decade,” said Vikram Kumar, country manager for Myanmar at the International Finance Corporation, the private arm of the World Bank Group.

Indeed, whereas Cambodia has had almost a decade to adjust to the administration’s banking framework and policies, this is, by comparison, still in its infancy in Myanmar. It is still a country characterised by an underdeveloped regulatory framework, poor financial and IT infrastructure, a lack of modern banking systems, inadequate transparency and adherence to corporate governance norms and, lastly, limited human resource capacity, Kumar said.

“Yet there is nothing in the list above that can’t be done through swift legislation and targeted investment but the more important question is how long will it take,” he added.

Real estate ‘bubbles’

In both countries, there is some concern over real estate ‘bubbles’ and, if popped, what affect this would have on the financial sector. The property consultancy Knight Frank published its latest Asia Development Index last year and found that Cambodia – or, more specifically, Phnom Penh – had the largest growth in residential and commercial land out of all Asean nations, for the first half of the year. With residential land rising by 14.1% and commercial 9.7%, this stood in stark contrast to an Asean-wide drop in growth from 3% to just 1.1%.

Knight Frank’s Cambodian country manager Ross Wheble told the Phnom Penh Post that such disparities were not unconnected. “[The Asean-wide fall] has benefited [Cambodia with] an influx of both foreign developers and investors seeking to take advantage of the comparatively low property prices and the relative ease at which foreign buyers can acquire freehold property.”

This might not, however, be as euphonious to investors as it appears. Higgins told Focus Asean bluntly: “I would be concerned if I had invested in the condo market in Cambodia.” Indeed, for almost two years economic commentators have been speculating when Cambodia’s property balloon will burst.

“However, with the bubble largely fuelled by cash offshore, the collapse of the bubble is unlikely to have a severe impact on the economy,” said Higgins. “The construction sector might hurt for a little while which will have a negative impact on growth, but the rest of the economy should be okay.”

In Myanmar, concerns over credit growth also exist. This is because 90% of Myanmar Bank’s lending is collaterised by land, said Kumar, adding that “with little capacity within the banks to actually assess repayment capacity, there is a lot of inherent risk in the financial system today. If real estate prices [adjust] significantly, banks will need to adjust their loan exposures and that would mean borrowers having to cough up the difference.”

Interview with Askhat Azhikhanov, CEO of ABA Bank in Cambodia

What are your thoughts on the growth of Cambodia’s banking and finance sector over the past decade?

It has grown significantly over the past decade. And it will grow even further, given the fact that Cambodia still has a low level of banking services penetration. In addition, Cambodia has a relatively low leverage of banking loan to GDP (56%) compared to the region’s peer countries (Vietnam has 114%, Malaysia has 145%, Thailand has 182% of GDP). That clearly shows that Cambodia still possesses strong potential for growth.

Among recent significant achievements in the industry that we can highlight is the creation of the Credit Bureau of Cambodia and the efforts of the National Bank of Cambodia in creating an interbank real time payment system. These initiatives strengthen the sector and speed up the development of the whole industry.

How has the growth of the internet in Cambodia affected the finance sector?

Cambodia largely benefits from rapid growth in the number of internet users in the country, especially among the so-called ‘generation Z’. They follow the global trends and seek new solutions for their everyday banking needs. Another aftermath of online growth is the great influence of social media on people’s lives and the way they do business. ABA has invested a lot in creating numerous channels of digital interaction between customer and bank.

We were the first bank to set up a 24/7 call center, which now receives hundreds of calls and online web chats every day.

We also were the first bank to introduce a full-scale mobile banking app in Cambodia last year. And we were the first bank to deploy an extensive network of self-banking kiosks, which allow a customer to deposit cash to bank accounts at any time of the day. All these technological advantages are now united under a multi-channel interaction system called Smart Banking. No doubt, we will introduce even more internet-based solutions to our customers that should facilitate their financial life.

Are you concerned about a real estate bubble and too much credit growth in a country like Cambodia?

Yes, there is certain anxiety regarding the real estate bubble, which may overheat the economy. And that is one of the reasons why ABA Bank participates in real estate lending with great caution. We rather focus on helping real sectors of the Cambodian economy, such as agriculture, retail trade, services, and others.

What can the banking and finance sector in Cambodia learn from other countries in Southeast Asia, say, Malaysia or Singapore?We can’t say that our present banking system is out of date; it is evolving dynamically. Of course, Cambodian banks can (and will) benefit from a close relationship with other SEA countries and that will only bring more benefits to our customers. We see great opportunities in developing digital banking solutions and remote self-banking services, as well as contactless payments, which are already commonly used in other countries.

And where do you see the banking and finance sector in years to come?

I believe in the continuous growth of the finance sector of Cambodia in coming years due to several reasons mentioned above. There is still a huge potential in introducing both basic and innovative digital products. At the same time, we expect certain changes in the banking sector itself. One of the reasons for that is the recent rise of capital requirement set out by the National Bank of Cambodia for commercial banks, which we find quite reasonable. This measure strengthens the banking sector as a whole and helps to ensure that banks maintain their financial stability

But, in turn, it will also cause certain consolidation in the sector, meaning that small banks will be merged with larger ones, bringing modified players to the market.

In numbers: banking

Rapid growth

Despite these problems, going forward there is a great deal of optimism in Cambodia and Myanmar’s banking industries, and few commentators would doubt that the future depends on how the sector adopts the latest digital technology. As Higgins said, there will be a “much greater reliance on technology, particularly around mobile payments” in the coming years, and banks and financial service providers will have to keep one step ahead of customer demand to succeed.

“The rapid growth in mobile connectivity and the consequent access to cellular data has provided a huge opportunity for financial services to leapfrog the traditional bricks and mortar model,” said Kumar.

Indeed, a 2015 report by Ernst & Young noted that banks will need to harness technology-driven innovation to both differentiate themselves and operate their business more efficiently. “In fact, the role of technology is so significant that we are seeing the lines starting to blur between technology companies and banks,” it stated.

The report advised that banks should consider four issues that would derive profit from heavy investment in technology: to innovate customer experience, especially for those who never held a bank account before; to introduce direct models of banking, such as online-only banks; to simplify user experiences; and to use mobile technology to engender financial inclusion, which means bringing financial services to those typically alienated from the industry.

What’s more, the same report identified an important future shift in how the industry operates: the transition from branches to ‘branchless’ banking.

“Currently, branch networks across APAC markets are not shrinking significantly – indeed, they are continuing to expand in emerging markets thanks to urbanisation and a growing middle class,” Ernst & Young reported. “But, as digital adoption increases, traditional branch usage will eventually decline. We expect branch footprints to contract, as regulatory restrictions around opening of accounts and provision of banking services relax and governments act to expand financial inclusion,”

Indeed, the CEO of Cambodia’s ANZ Royal, Grant Knuckey, told the Phnom Penh Post recently: “I don’t see massive branch expansion being a theme going forward. I see a consolidation in terms of branches.”

Digital banking

If Knuckey is correct, then in the coming years, Cambodia will see the slow retreat of branches, making way for less expensive, and more assessable, digital methods. However, this will require a great push by the industry players to convince Cambodians to trust e-commerce and cashless payments. Currently, only 40,000 people in the country possess credit cards, and 1.5 million people – or 10% of the population – have bank cards, according to government statistics. Nevertheless, many banks in Cambodia are pre-empting the population moving to plastic, and have already begun offering clients online banking services.

In Myanmar, however, the transition from cash to plastic, and in-branch to online, will undoubtedly take much longer. According to Kumar, Myanmar’s financial sector has been somewhat behind its economic growth, and added that this is slightly odd since in most countries “the financial sector is the driver of the economic growth… given that the capital multiplier is maximum in the financial sector. However, in the case of Myanmar, it is safe to assume that growth is taking place in spite of a very underdeveloped financial sector.”

Nevertheless, there is now pressure on domestic banks to prepare themselves to cope with the demands placed on them by the expected pace of economic growth, Kumar said. As a consequence, “most banks have upgraded or are in the process of upgrading their technology capacity.”

“Growth in digital connectivity in Myanmar allows the introduction of branchless banking, through ATMs, mobile phones and internet. However, on the flip side, the infrastructure is not yet reliable. The industry is still at a very nascent stage with multiple teething woes,” Kumar said. “For wider use of these new delivery channels, it is critical to improve both the level of financial literacy and security protocols while expanding the capacity of the central bank to manage this growth which could turn out to be exponential in the medium to long term.”

This, he added, will help Myanmar fully realise the true potential of the digital financial revolution.