Editor’s Note: As we enter a new decade, Southeast Asia looks to be on the precipice of enormous growth, change and upheaval, with the potential to be both revolutionising or injurious in its impact. From evolving geo-political relations with the world’s great powers, to economic opportunities arising from the US-China trade war, as well as the ever-looming threat of climate change, 2020 is set to be a crucial year for the ASEAN countries. Here, Southeast Asia Globe guides you through some of the top issues set to mould the region in the year to come, as well as introduce the themes and issues that our editorial team will devote special attention to through our four pillars of Power, Money, Life and Earth.

Power

US pullback – China filling the void?

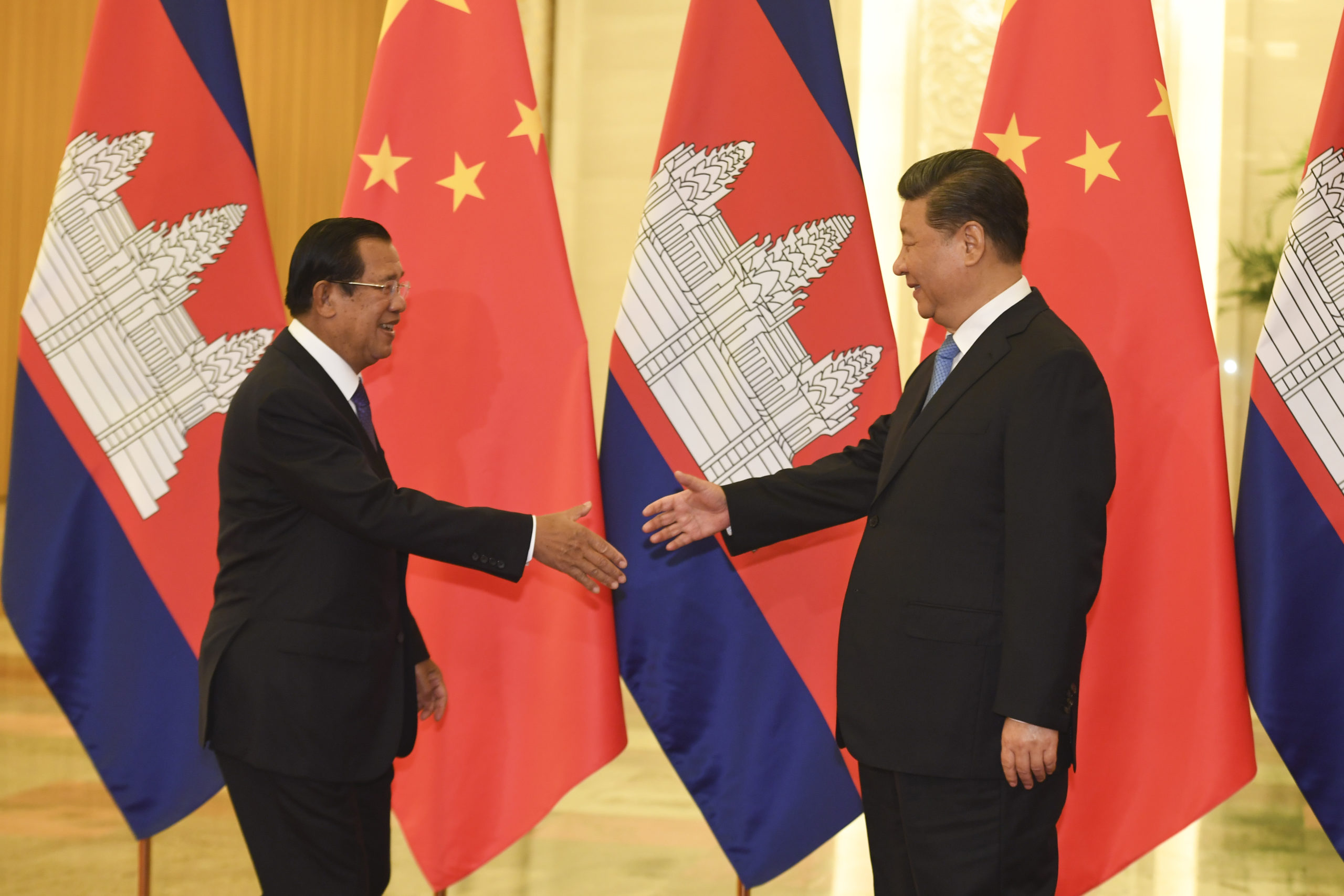

When US President Donald Trump declined to attend the 35th Asean Summit in Bangkok in November – the second year in a row he has done so – observers saw it as deeply symbolic of the changing nature of ASEAN’s relations with the great powers. Sent in his place was National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien, the lowest level representation by the US at the meetings since Barack Obama upgraded ties with the 10-member bloc in 2011. In response, ASEAN nations snubbed a US summit as part of the Bangkok gathering – an ominous harbinger of growing resentment towards the once great ally. But as the US retreats, China is filling the void.

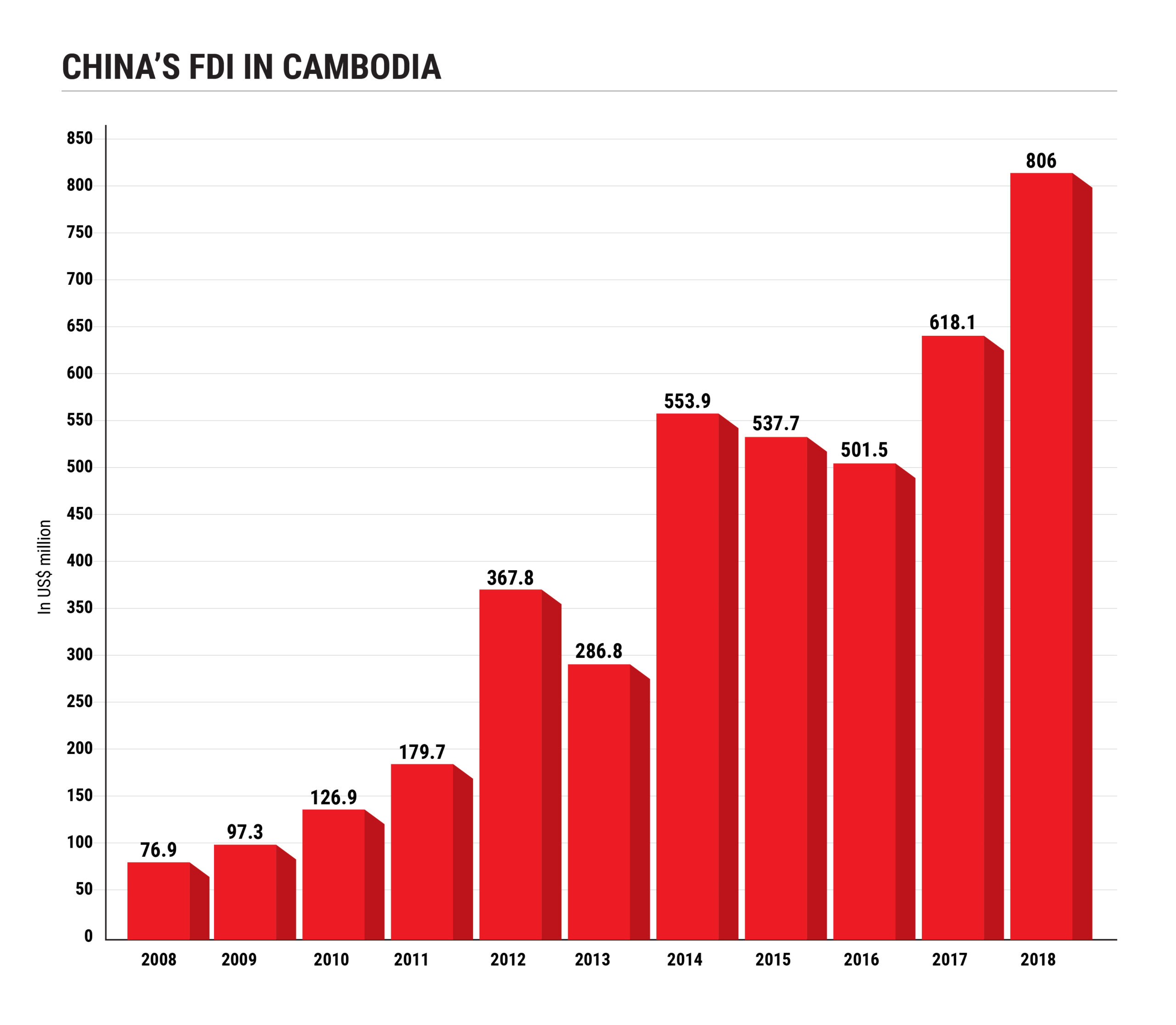

Cambodia is the most prominent example of this, where relations with the US (and Europe) are more strained than ever over charges of declining democracy and human rights in the Kingdom. Conversely, Cambodian relations with China are cosier than ever – perhaps dangerously so – as a result of vast investment by Beijing as part of their Belt and Road Initiative that has seen money flood into the whole region. This is a dynamic that will play out, with great consequence, in 2020 and the coming decade.

Upcoming elections

2020 will see Singapore and Myanmar – two countries poles apart economically and politically – head to the polls for two very different general elections. In Singapore, Southeast Asia’s epitome of stability, the People’s Action Party (PAP), which has dominated politics since independence, looks set to comfortably win the as-yet undated polls – mandated to be held by April 2021, but likely to occur sooner – despite a minor surge by a new opposition coalition.

In Myanmar – a country condemned for alleged genocide against the Rohingya minority, as well as ongoing internal conflicts nationwide – things look less certain. Myanmar’s de-facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s dramatic transformation from democracy icon to defender of rights abusers was complete in December as she attended the International Court of Justice in The Hague to defend her country of charges of genocide. While her increasingly nationalistic rhetoric has solidified her popularity among the majority Bamar ethnic group, it’s also alienated some ethnic minority groups, so crucial to her sweeping landmark electoral success in 2015. While a complete electoral loss in the undated polls for her National League for Democracy party seems highly unlikely, her unpopularity in conflict states away from the centre may lead to the election of fringe parties to parliament, and ultimately increased political instability.

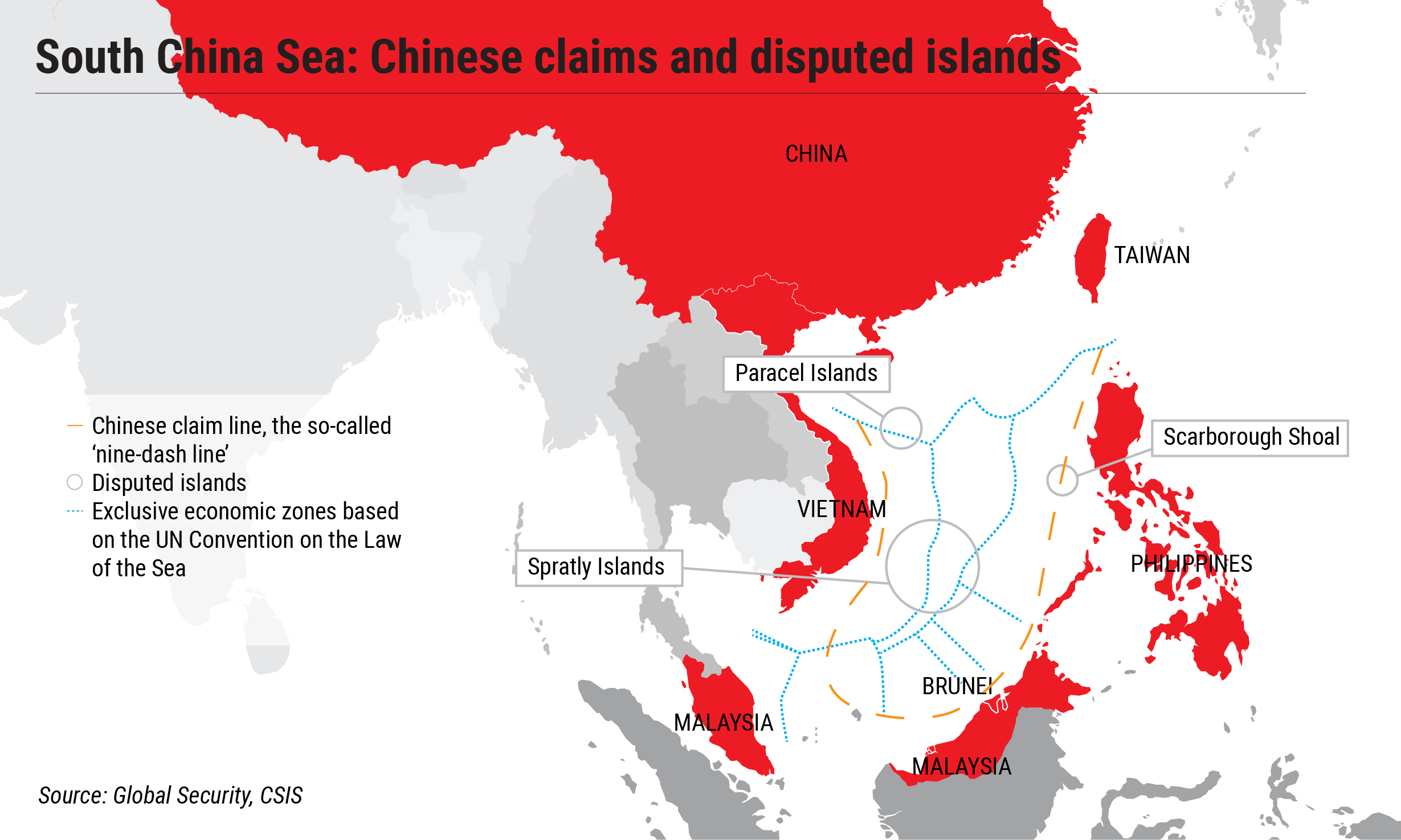

The South China Sea

Last year proved another contentious one in the hotly contested South China Sea, with several tense stand-offs between China and Southeast Asian nations. Vietnam and China had arguably the most heated of these in July, when a three-month confrontation erupted between the two nation’s navies. By the third day of our new decade it was clear that the South China Sea was set to be a continuing source of tension in the region, when Malaysian Foreign Minister Datuk Saifuddin Abdullah provoked the fury of Beijing when he confirmed his country would continue with their claim, filed to the UN in December, to an expanded portion of the sea.

Money

US-China trade war

Last year saw the US-China trade war – an economic confrontation initiated in 2018 by president Trump in the form of tariffs to address “unfair trade practices” by Beijing – saw a dramatic escalation that has shaken China, as well as the global economy at times. As of December 2019, the US had placed $550 billion in tariffs on Chinese goods, while Beijing has set $185 billion of its own. The implications of the trade war on Southeast Asia remain unclear going into the new decade, but currently, the region seems to be winning.

In one sense, opportunities abound as Chinese manufacturers relocate to the region (Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia in particular) at an increasing rate, partially driven by rising labour costs in China and partially to circumvent US tariffs. Nintendo, Sharp, and Kyocera in 2019 all announced plans to shift some production from China to Vietnam for example. “By and large Vietnam is winning the US–China trade war, and I expect them to continue to win it,” Eric Miller, a global fellow at the Wilson Center, told WIRED in August.

Conversely, the highly damaging effect of the trade war on China’s slowing economy inevitably has a knock-on effect for Southeast Asia, a region so reliant on its trade. For example, Indonesia saw exports to China, its biggest trading partner, drop 11% in 2018 – the year the trade war started. As 2020 progresses, Southeast Asia’s winners and losers in the trade war will become more apparent.

Everything But Arms

In February 2019, the EU officially started it’s procedure to potentially suspend or withdraw Cambodia’s access to its Everything But Arms (EBA) preferential trade status for exports into the 28-member bloc, citing concerns over the “deterioration of democracy, respect for human rights and the rule of law”.

With Cambodian exports to the EU amounting to some $5.8 billion in 2017 – 40% of total exports, and only second to Bangladesh among EBA beneficiaries – the withdrawal of the Kingdom’s tariff-free access could hit the economy for up to $654 million per year, hurting an estimated 700,000 garment workers hardest. With a final decision set to be made in February, it seems the Cambodian government’s efforts to appease the EU have proved insufficient. Should EBA be removed, this will likely only see Cambodia move closer to patron China both economically and politically in 2020, but becoming overly reliant on Beijing is not without its risks.

In Myanmar, similar concerns abound regarding human rights abuses – particularly in Rakhine State since 2017 – with the EU currently considering whether it will commence a similar process of assessment for the country. For Myanmar, another one of Southeast Asia’s poorest nations, the effect of this on its economy in 2020 and beyond could be devastating.

ASEM Summit

Cambodia is set to host 50 international leaders at the 13th Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) in Phnom Penh on 16-17 November under the theme ‘Strengthening Multilateralism for Shared Growth’. Covering political, economic, security and cultural cooperation, ASEM member countries – which includes all 28 EU states and China, but not the US – account for 50% of the world’s GDP, 60% of global trade and 60% of the world’s population. With tensions between Cambodia and the West at an all-time high, the summit could prove a telling barometer for future relations.

Life

Human Rights

Respect for human rights remains a fundamental issue across the region going into 2020. In the Philippines, president Rodrigo Duterte’s ongoing drugs war continues to see thousands of citizens killed (more than 7,000 since he assumed office in 2016), with Amnesty International saying in December the government was continuing to “get away with murder”.

In Myanmar, the ongoing plight of the country’s many ethnic minorities, most notably the Rohingya, at the hands of the military is an issue with seemingly no end in sight. But these are merely the stories that make the headlines, with Human Rights Watch’s 2019 World Report citing concerns over torture and enforced disappearances in Thailand, LGBTQ rights and freedom of religion in Indonesia, freedom of expression and the press in Vietnam, LGBTQ rights in Malaysia and Brunei and freedom of the press and expression in Singapore.

Press Freedom

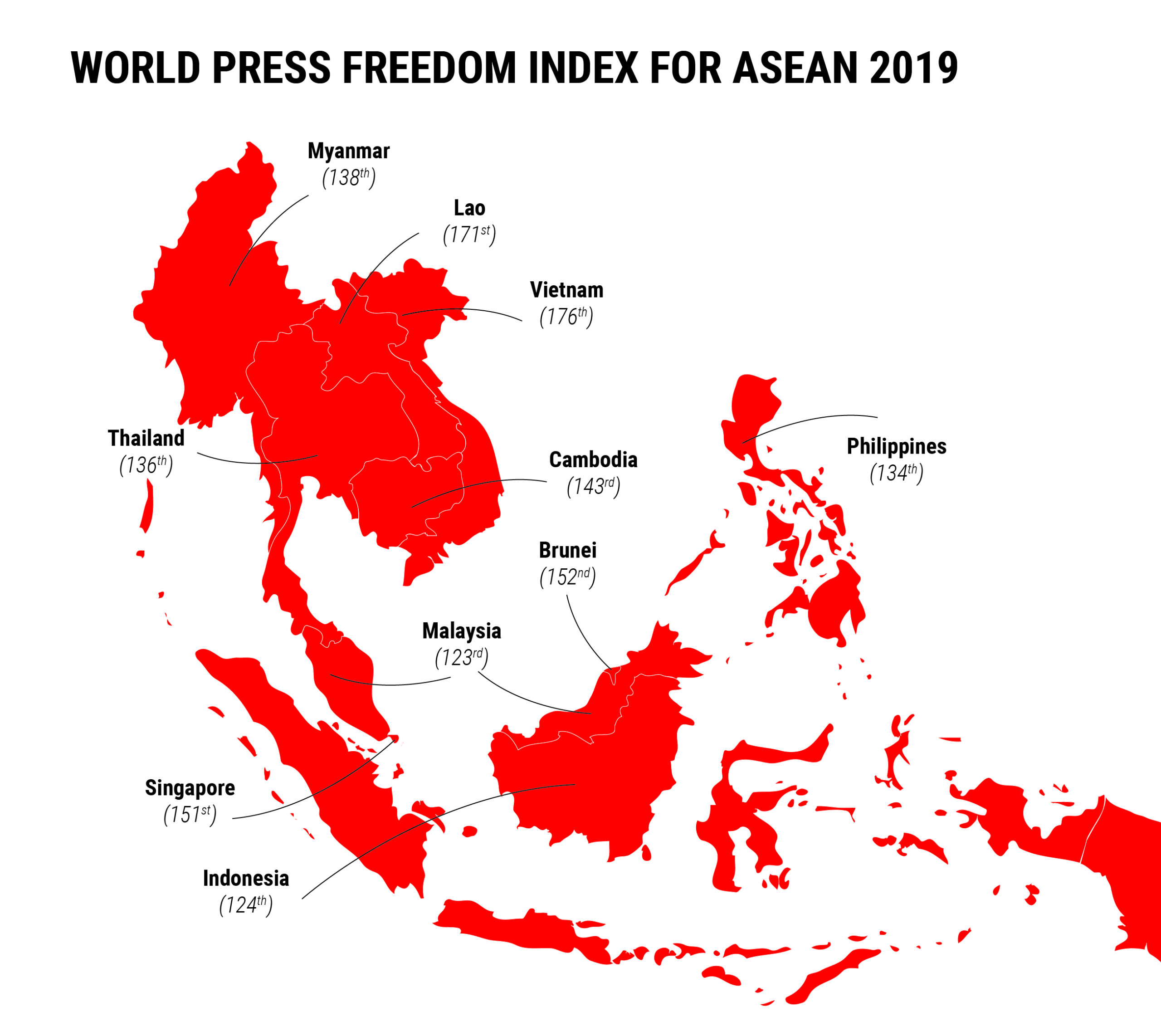

Press freedom is set to continue to be an issue across the region going into 2020. The Philippines, among the deadliest in Asia for media workers in recent years, looks to be doing little to address this issue, as its prickly leader Duterte continues to battle with members of the press, particularly the female-led team of outlet Rappler and its CEO Maria Ressa.

The situation is little better across the region, where in Cambodia outlets such as the Cambodia Daily and the Phnom Penh Post have either been closed down or taken over by individuals with close ties to Hun Sen’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party in recent years. While in Myanmar, two Reuters journalists were freed in May after over 500 days in detention for reporting on the massacre of Rohingya civilians by the Burmese military – a concerning sign of things to come for freedom of the press in the nascent, fragile democracy. This, a mere snapshot of an ongoing trend of repression of the free press in Southeast Asia, looks set to continue throughout 2020.

Automation

While 2020 is unlikely to be the year we see Southeast Asian workers replaced by their robot counterparts, it represents one step closer to a seemingly inevitable future in which 56% of the salaried workforce from Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam are at “high-risk” of losing their jobs to automation. How will countries like Cambodia, with a low-skilled workforce ripe for displacement, adapt in the coming years?

Earth

Rising Sea Levels

Climate change is the preeminent issue of our time, with 2019 seeing teenage climate icon Greta Thunberg rising to prominence as Time’s Person of the Year. Southeast Asia looks particularly vulnerable to issues such as flooding, with projections showing that the region is set to be hit hardest globally by rising sea levels in the coming years.

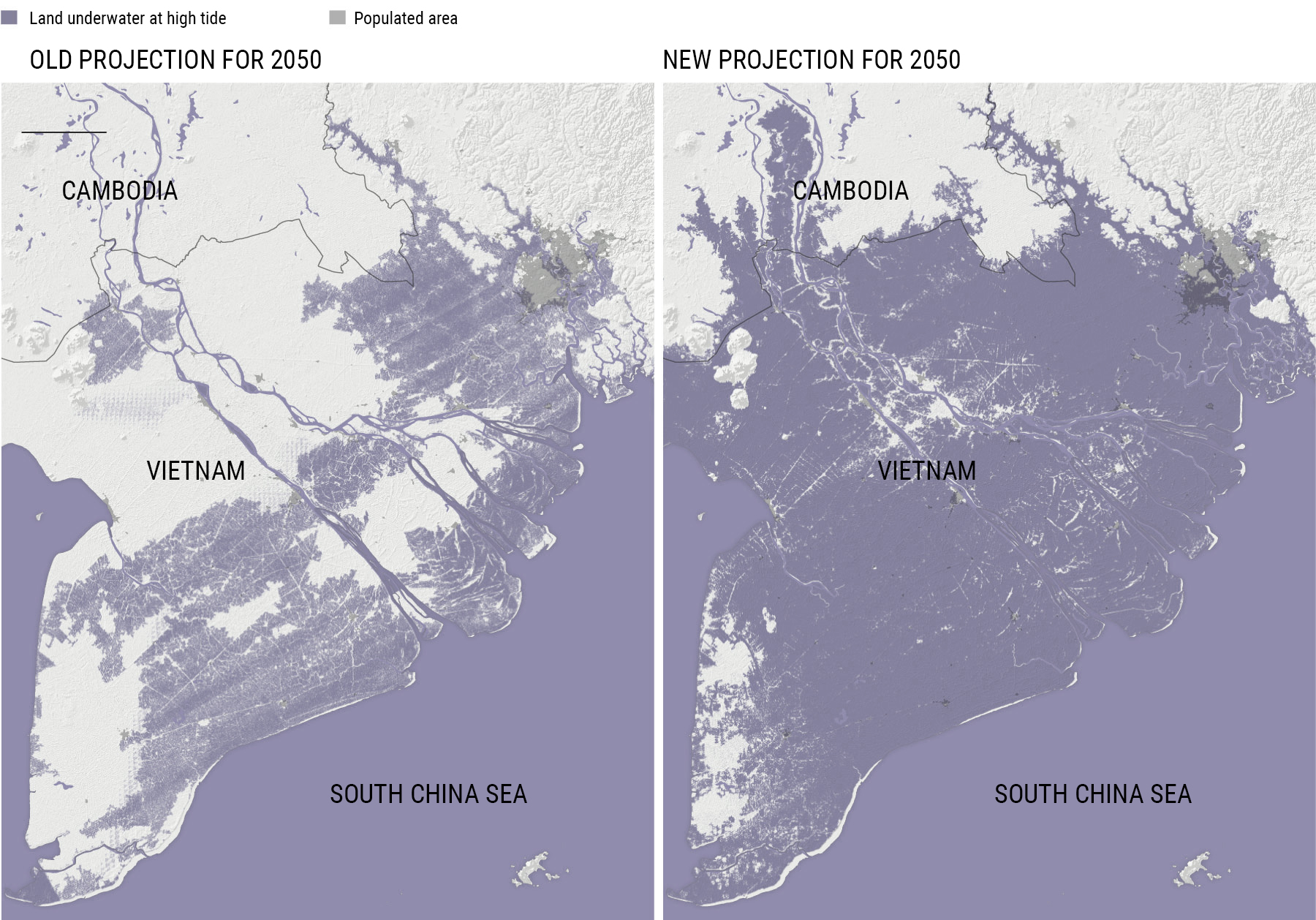

Moreover, according to the Global Climate Risk Index, Vietnam, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Thailand are among the 10 countries in the world that have been most affected by climate change in the past 20 years. In October, new projections showed that 150 million people – the majority in Southeast Asia – are living on land that will be below the high-tide line by 2050, with southern Vietnam, including Ho Chi Minh city, all but disappearing. As the clock ticks and time to address the problem rapidly runs out, 2020 will be yet another critical year for countries across Southeast Asia to make preparations to avoid this creeping disaster.

Dams on the Mekong

Going into 2020, dams on the region’s major waterways are increasingly a threat to livelihoods, species and communities. In July, the Mekong River Commission reported that water levels on the river had dropped to historically low levels, with fish stocks declining as a result. While unseasonably low rainfall was cited as one cause, so too was maintenance work at China’s Jinghong hydropower station and tests at Laos’ Xayaburi dam.

“This is about food. This is about life or death. It would be better to suspend or cancel all the dams and seek other alternatives to produce electricity,” a member of the Thai People’s Network in Eight Mekong Provinces told Radio Free Asia’s Lao Service as the Xayaburi dam officially began operating in October. As communities lining the river suffer, resistance to the construction of new dams, and the operation of current ones, is sure to increase going into 2020.

Species extinction

In November, the last Sumatran rhinoceros in Malaysia died, with a population of 80 living in Indonesia the last remaining globally. While in Cambodia, hydropower dams have resulted in shrinking of the Irrawaddy dolphin population in the Mekong River to just 92, according to WWF, with warnings that the species may become extinct within years. Region-wide thousands of species face a similar fate, with habitat destruction, rampant poaching and even a growing hunger for traditional Chinese medicine putting Southeast Asia’s bio-diversity at serious risk going into 2020.