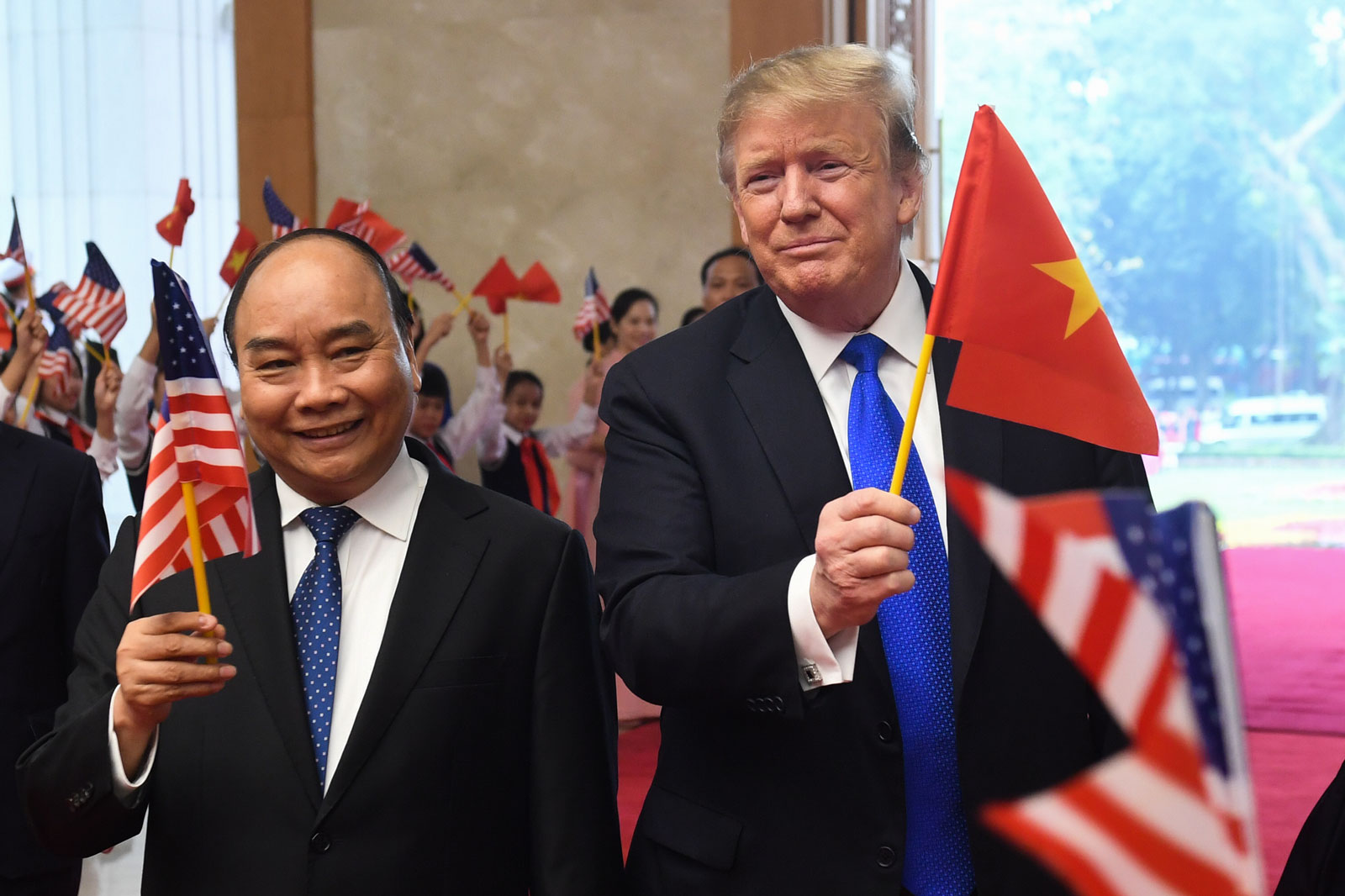

Many people would be surprised to learn that Vietnamese PM Nguyen Xuan Phuc was the first ASEAN leader to meet US President Donald Trump in 2017. Then, before heading to the White House, Phuc pledged to rebalance the US-Vietnam trade relations, with the deficit consistently on the former side since 1997. The Vietnamese enterprises escorting him would also sign business deals worth more than $10 billion, in an apparent charm offensive to President Trump’s protectionist stance.

Two years on, the pledge is unlikely to be fulfilled, as Vietnam has emerged as the key winner in the ongoing US-China trade war. In the first five months of this year, Vietnam exported a total value of $22.6 billion to the US, a sharp 36% increase year on year, partly thanks to the so-called goods diversion. Vietnam became the eighth-largest source of US imports, enjoying a 39.5 billion trade deficit.

It is not just trade. Many foreign companies – fearing the worst of the trade war – rushed to find alternative manufacturing locations to avoid rising tariffs. Being close to China, having a huge working population, enjoying a stable political and economic environment, Vietnam is naturally an ideal choice for this China-plus-one policy. The country has seen a 70% increase of FDI inflow in the first five months, energised also by Chinese investors.

The statistics and the hypes all look good, but a deeper analysis would make optimists more cautious.

First, rising US tariffs against Chinese products inevitably leads to the temptation of “transshipment”, when companies cheat by exporting their products via Vietnam without actually manufacturing here. This gives the country no added values, and worse, makes it an attractive next target for Trump. In June, Trump called Vietnam “the single worst trade abuser”, leading Hanoi to quickly compromise by pledging to buy more US goods. Shortly afterwards, the US Commerce Department slapped a 456% import duty on Vietnam’s steel products, accusing it of circumventing the US anti-dumping and anti-subsidy duties on products of Korean and Taiwanese origins.

On the other hand, Chinese products that cannot make it to the US have found their way to their Southeast Asian neighbors. This will in turn crowd out Vietnamese goods, making life harder for domestic manufacturers.

The same caution can be reserved for FDI as well. The country cannot be compared to China in terms of production scale, logistics, infrastructure, labour quality, and market size. A sudden surge in FDI would then strain Vietnam’s limited capacity, artificially raising the cost of doing business. In addition, Hanoi already has a serious problem of industrial pollution, highlighted by the massive Formosa steel plant scandal in 2016. More low-end and low value-added factories will only intensify the environmental concerns. The government is trying to attract more hi-tech manufacturers, like Samsung or Intel, but this would require Hanoi to do much more homework. Take labour quality for example: as 80% of Vietnamese labour force are untrained, it is hard to imagine that the country can quickly absorb the hi-tech outflow from its giant neighbour.

Furthermore, Hanoi understands that the quarrel between the US and China is not just about economic benefits. Trade is only a part of a broader strategic confrontation between a current superpower and a rising one who wants to exert more influence. Vietnam will look much more vulnerable if this geopolitical rivalry accelerates. Suffering from the economic slowdown, China might raise their nationalist card to bolster their legitimacy at home. Vietnam – as one of the most vocal claimants in the sovereignty disputes with China – risks being its prime target.

Since the start of the trade war, Beijing has been much more aggressive on the South China Sea, where it makes a vague “nine-dash line” claim over 80% of the contested waters. Last month, it sent a survey ship with armed coast guard vessels to Vietnamese Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) waters, close to Vietnam’s strategic oil and gas exploration areas. They were closely followed by Vietnamese ships, raising fears of escalating confrontation. It was the first time such a standoff has happened since the similar incident in 2014, which brought the two communist regimes’ relationship to the lowest point since their bloody border war in 1979. A massive anti-China protest broke out following the event, leading to rare unrest and riots nationwide.

It is ironic that its former diehard enemy turns out to be Vietnam’s main protector in its dispute with China. In the latest incident, the US was the first nation to criticise China, accusing Beijing of bullying behaviors and “provocative and destabilising activity”. Washington has been challenging Beijing’s position on the South China Sea since 2010, when the then-secretary of state Hillary Clinton called the area key to America’s “national interest”. It frequently carries out so-called “freedom of navigation” patrols in spite of Beijing’s strong objection. The more aggressive China’s stance on the South China Sea, the more likely that Vietnam will continue shifting towards the US. Yet certainly, communist leaders in Hanoi know that moving away from its ideological partner is not simple.

A wrong choice – or no choice at all – could very well turn the fortune of the trade war around for Hanoi

As such, Vietnam with its unique position is very easily dragged into this Thucydides Trap of two global superpowers. The last time this happened, Vietnam was mired into an infamous war which devastated the country for decades and killed more than 5 million people. No one in Hanoi would like to see that scenario happens ever again. Consequently, walking a fine line between the two remains a tough task for Vietnamese leadership. A wrong choice – or no choice at all – could very well turn the fortune of the trade war around for Hanoi.

Nguyen Khac Giang is a PhD candidate at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, and a senior research fellow at the Vietnam Institute for Economic and Policy Research (VEPR), Vietnam National University, Hanoi.