The rapid spread of social media is altering Cambodia’s political landscape, and the old guard is struggling to keep up

By Colin Meyn

Five years ago, around the time that Prime Minister Hun Sen’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) swept the 2008 elections, winning three-quarters of the seats in parliament, fewer than 10,000 Cambodians had regular access to the internet. Facebook had only just begun to spread beyond college campuses in the US and was unheard of among most Cambodians. The idea that five years later, social media, and particularly Facebook, would pose one of the greatest threats to the status quo in Cambodian politics would have seemed far-fetched.

Internet access is becoming less of a luxury in the country, and the cost of web connections and smartphones is dropping by the day. Established brands such as Samsung and LG, along with Chinese brands including Huawei, are in a race to the bottom in the developing world, where high-tech phones can now be bought for less than $100. In Cambodia’s over-saturated telecommunications market, the price of an internet connection is also plummeting, with companies offering unlimited broadband in some areas for $12 a month.

It is estimated that there are 19 million mobile phones in Cambodia – 1.3 phones for each of the country’s 15 million people – and an increasing percentage of them connect people not only to their friends and family, but also to the worldwide web.

Currently, more than two million Cambodians are connected to the internet and, unless the government decides to do something to stop it, that number will increase exponentially in coming years. The impact of this will be felt in all spheres of society, but in politics, where Hun Sen has carefully taken control of every state institution and enjoys a stranglehold on mass media, the impact could be revolutionary.

The internet’s possibilities within Cambodian politics have already been felt. In July’s election, the CPP was humbled for the first time in 15 years. It lost 22 seats in the National Assembly in an election environment that heavily favoured the ruling party. The opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) has proven itself to be the greatest threat to Hun Sen’s power since the royalist Funcinpec party in the years following United Nations-sponsored elections in 1993.

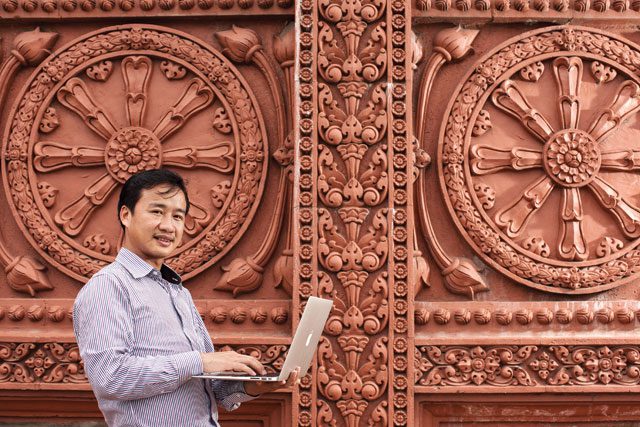

Whether the CNRP’s aggressive campaigning on social media had an impact on the election results is difficult to say, but it certainly didn’t hurt. Last month, opposition leader Sam Rainsy passed 250,000 fans on Facebook and CNRP vice-president Kem Sokha passed 200,000. Both Rainsy and Sokha hired young people equipped with video cameras and laptops to track their every move and post updates to Facebook before and after the election.

The CNRP also enlisted youth activists to set up satellite Facebook pages in their constituencies. Suon Chamroeun, a CNRP youth leader in Battambang province, credited the opposition party’s online presence for the huge turnout at the opposition rallies leading up to the election.

“Facebook was really important when we got people together to join the campaign, especially when my president [Rainsy] came to Battambang. I posted to the wall on my profile and others in the party also posted it. In only two days, we were able to get 100,000 people to join,” he said. Estimates of the size of the CNRP rally were in the tens of thousands, but through grassroots organisation and online campaigning, CNRP rallies have continued to draw some of the biggest crowds that democratic Cambodia has ever seen.

Chamroeun said that the spread of internet access through smartphones was enabling the party to not only connect with individuals, but with entire families that may otherwise be difficult to reach.

“The smartphone is [becoming] cheaper and cheaper, so even farmers can get one. In some villages, they have two or three smartphonesand they share with each other. I am not sure about the next step of my party, but if we have time, we should train the villagers in how to use a smartphone,” he said.

More than a third of the electorate – 3.5 million people – is under the age of 30, and political analysts credit much of the opposition’s success to the increasing importance of Cambodia’s young voters. Denis Schrey, head of the Cambodia office of Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, which runs a program to train young politicians in Asia – including members of the CPP and CNRP – said that both parties face challenges in boosting their support among young voters. When it comes to social media, however, the CNRP has taken an early lead in the race toward the 2018 national elections.

“[The CPP] needs to build a strong national communications structure that includes young people and tries to promote the party through social media on certain issues. They have not decided that social media is a priority and don’t have a competent team of people to communicate these messages. The CNRP seem to be far ahead of the CPP because they have had to [spread their messages] with social media and communications,” Schrey said.

During an epic six-hour speech following the formation of a new CPP government, which pushed ahead despite a boycott of the National Assembly by 55 CNRP lawmakers, Hun Sen laid out a broad platform of reform and promised not to shut down Facebook – a situation feared by many in civil society who think the CPP may not be willing to tolerate a public platform for popular dissent.

“The government has no policy to close Facebook, but I would like to appeal to people not to let Facebook become a tool to damage social stability and insult people. The government encourages youth to use Facebook, we encourage them to use [the internet] and the speed should be fast so that they can share updated news. We can take advantage of Facebook to serve the people’s interest,” Hun Sen said.

“I think the CPP is recognising that social media is becoming an important tool,” said Pa Nguon Teang, director of the Cambodian Centre for Independent Media, citing the many references to Facebook in the prime minister’s first major speech after being sworn in for another term in power.

Teang added that the page for ‘Samdech Hun Sen, Cambodian Prime Minister’ has become markedly more active since the election. Numerous photos were posted from his trip to Brunei for the 23rd Asean summit in early October, as were photos of government officials responding to flooding that affected much of the country last month. Hun Sen has previously denied that he has an official Facebook page, but that remark was made the day after Sam Rainsy celebrated passing the prime minister in online popularity. In early October, Hun Sen had about 120,000 Facebook ‘likes’ – less than half of the opposition leader’s tally.

Leaders of the CPP youth, including Hun Many, the prime minister’s son and a newly elected member of parliament, declined to be interviewed for this story.

The CPP will likely use the same strategy on social media that it has in the many channels of mass media that it controls, said Teang.

“The tool is different but… even on Facebook it is nothing more than propaganda from high-ranking officials with power, such as the prime minister. They use Facebook to attack others and spoil the environment,” he said.

By turning the majority of traditional mass media into a propaganda tool for the party, the CPP has inadvertently accelerated the use of Facebook and other online media that offer a less-filtered version of events, said Samdy Lonh, 29, a computer programmer who has worked on Google’s expansion into Cambodia. “Social media is different than traditional media; social media is the counter-

discussion media. Everyone can fight each other,” he said, adding that the ruling party would have to make good on its reform promises if it wants to leverage social media for its benefit. “If the CPP wants to make themselves successful on social media, they need to be good first.”

Despite Hun Sen’s promises, fears linger over Facebook’s future in Cambodia. According to Tharum Bun, 31, one of the country’s first bloggers, any attempt by the government to discredit Facebook would likely fall flat.

“Criticism [from the government] about Facebook as trash or where young people get polluted, I don’t think it will make [the government] become popular at all,” said Bun, who works as a social media consultant in Phnom Penh. “Can the CPP use these same tools to make themselves more popular? It’s possible. I think people talk about whether they are willing to reform or not, and if they do it seriously, Facebook is just another media machine for the government.”

Whether or not the ruling party embraces social media, CPP-friendly media outlets – which have refused to cover opposition rallies or give any air time to CNRP leaders – will have to reconsider their strategy if they hope to have any significance for Cambodian youth, said Ou Ritthy, 26, a prominent political blogger with a large social media following.

“Why is Facebook so popular here? In Thailand or other countries, they have better media – mass media, newspapers and TV that helps to inform people,” Ritthy said. “There is no alternative choice for people here. Big public opinion is showing the CPP that it’s time to think about mass media. Think about how you advertise your party. It’s not effective, so change. Make something more relevant.”

Also view:

“Apportunity knocks” – The increasing digitalisation of Southeast Asia is creating greater opportunities for startups, although it is foreign entrepreneurs who are leading the pack

“School’s out…” – An online movement sweeping the world has the power to change education as we know it

“Digital Khmer script: Cracking the code” – The quest to keep the Khmer script alive in a digital world