With concerns that reform has stalled, critics are questioning the Obama administration’s strategy towards Myanmar

In her memoir, Hard Choices, Hillary Clinton describes her first meeting with Myanmar’s opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi in December 2011 as “a delicate moment”. The Obama administration’s opening to the country is to many a signature achievement of Clinton’s tenure as secretary of state. While unlikely to play a major role in Clinton’s presidential campaign, the easing of US policy toward Myanmar is an important foreign policy initiative and one that is now at its own delicate moment and in danger of unravelling.

In 2011, with Clinton at the State Department, the administration began to loosen the tight US Myanmar policy as part of its Asia “pivot”. Steps would include easing economic sanctions, restoring diplomatic relations and limited military cooperation following signs of democratisation in Myanmar. The shift grew from a desire to respond to and encourage reform and a belief that US policy aimed at isolating Myanmar had run its course. Once US policy eased, everyone else started pouring in – and there’s the rub.

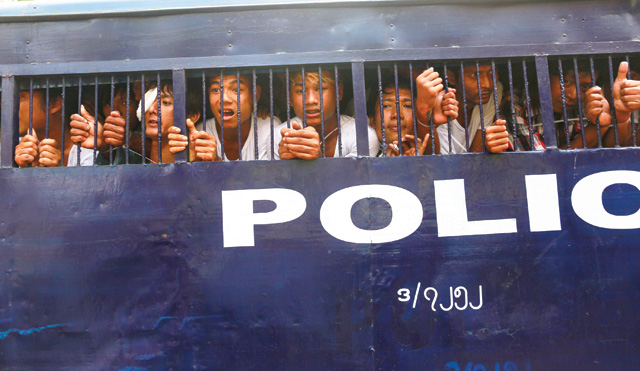

Few would dispute that Myanmar has seen major changes, including a nominally reformed government, Suu Kyi’s release from house arrest and election to parliament, and the release of political prisoners. Problems nevertheless continue, including the jailing of reporters, attacks on Muslims – particularly in Rakhine state – arrests of student protesters and decades-old fighting with ethnic groups. Myanmar signed a draft ceasefire in March with 16 ethnic groups but the jury is out on the signing’s significance.

In addition, Suu Kyi is constitutionally prohibited from running for president in landmark elections this year, because the constitution bars foreign nationals or anyone with a foreign national in their immediate family from becoming president – Suu Kyi’s late husband was British and so are her two sons. That is not likely to change because the military, with a constitutionally guaranteed 25% share of parliamentary seats, can block amendments.

Suu Kyi told Reuters in April that boycotting the election was possible if the constitutional language is not changed. She also said President Thein Sein might try to postpone the poll – which she called “the real test of whether we are on the route to democracy or not”.

A growing number in Congress and elsewhere in Washington now worry that Myanmar’s reforms have stalled and have started to question the administration’s strategy. A key contention of the critics is that the administration erred in abandoning an action-for-action policy, which conditioned future US concessions on specific actions, a change they say has helped Myanmar open to outsiders but exerts no pressure for further reforms. As one congressional staffer, who insisted on anonymity, put it, many members of Congress support Suu Kyi and want to see Myanmar’s reforms stick.

“However,” the staffer said, “we’ve seen, this year already, things have been happening, whether it’s the fighting in the ethnic areas, these protests, that what we thought was a reformed government or a reforming government, as the administration has continually come in to tell us, that’s not what we’re seeing. Their actions are telling the international community that their interests don’t matter.”

Another staffer was more charitable, saying, despite some improvements, there remain many reasons to be sceptical about progress in Myanmar. “It’s a mixed bag at best and it’s likely to be a mixed bag at best for a while to come,” he said. The staffer pointed to the implementation, rather than the design, of the administration opening as the problem. He said he did not think the policy is in trouble in Congress “yet”.

“I think a lot hinges upon … frankly, how things unfold over the next six months in the run-up to the elections and then the elections themselves,” he said.

Among congressional sceptics is Joseph Crowley, a Democratic member of the House of Representatives, who said he thinks the administration “is starting to understand that things aren’t going as hunky-dory as they’d hoped”.

“They may have free elections but I question whether they’re fair when 25% of the legislature’s controlled by the Burmese military and they don’t allow everyone to run for president,” he said. Crowley said he does not necessarily object to the policy if Myanmar “is taking actions that we believe are positive”.

“If the administration gets back to an action for action, I’m for that,” he said, “I’m for rewarding good policy movement within Burma. But I’m not for simply turning around and making believe that everything’s going great when it’s not.”

Others in Congress, including Republicans and Democrats, have recently raised concerns about the administration’s Myanmar policy, but a notably missing voice has been that of Senator Mitch McConnell, the Republican majority leader who has long been a leader on the issue and is reportedly close to Suu Kyi. He did, however, make revealing comments on the Senate floor last July.

He acknowledged that, in many ways, Myanmar hardly resembled the Myanmar of 2003, when Congress passed import sanctions legislation, saying that in recent years the country had begun “to make significant strides forward in several key areas”. Myanmar, McConnell said, had started to “institute reforms that surprised virtually all onlookers”, adding that in light of reforms “I believe that to no small degree Burma has been a remarkable story among many dark developments in the world today”.

While many see Myanmar as having “stalled”, he said elections, including this year’s poll, give reformers “an opportunity to regain their momentum”. He called the time until the end of this

year “pivotal”, saying the elections “will help demonstrate whether the country will continue on the reformist path”.

“With that in mind,” he said, “the Burmese government should understand that the United States, and the Senate specifically, will watch very closely how Burmese authorities conduct the 2015 parliamentary elections as a critical marker of the sincerity and sustainability of democratic reform in Burma.”

McConnell cited the constitutional language barring Suu Kyi from running for president, saying: “To me, it will be a missed opportunity if this provision is not revisited before the 2015 parliamentary elections.”

Some US sanctions remain, including restrictions on jade and ruby imports and sanctions against individuals hindering reform. “It is hard to see how those provisions get lifted without there being progress on the constitutional eligibility issue and the closely related issue of the legitimacy of the 2015 elections,” he said.

The administration, however, defends its policy, saying the situation is more complicated than critics make it out to be. A senior administration official, insisting on anonymity, said the administration did not share the “euphoria” after early reforms, certain even then that change would be slow.

He defended the change from an action-for-action approach. “It wasn’t a transactional thing. It was more a trust-building exercise,” he said. Later, he said, the administration began to see change and concluded that it needed to take more initiative. The administration shift was made, he said, “because we made a judgement, and I think it has been borne out, frankly, that our proactive engagement will get better returns than waiting to react to events on the ground”. The official pointed to “a continuation of the liberalisation on many fronts”.

“I mean,” he said, “is imposing sanctions or keeping sanctions in place going to give you peace? Is it going to give you changes in Rakhine state? Is it going to force a change in the constitution?

“We are not going to make the difference in the success or failure of this country.

“We can give it a chance to succeed, we can want it to succeed, we can invest in its success, but ultimately the people of this country are going to have to make it work, and what we are doing, and I’m fully confident that it has been the right approach, … is proactively trying to help this country get through a very difficult time in an extraordinarily complex environment, to succeed or at least to be on

a path to success, and that success includes democracy, freedom and economic development and peace.”

Administration policy, he said, has helped that process but he said it would take time and there will be setbacks. “I think everybody has to take a deep breath, not accept setbacks, but understand that there are going to be steps forward and perhaps some steps back and be patient on trying to work to assist this place and that there is no country that undergoes transition that doesn’t have problems,” he said. “We’re seeking their success, not their failure.”

Suu Kyi raised concerns in her Reuters interview, questioning whether US praise makes Myanmar’s government “more complacent”. She termed the United States and the West overall “too optimistic”, calling for “a bit of healthy scepticism”.

Steve Hirsch is a Washington-based journalist who has been reporting from the US capital since the 1970s. He frequently reports on the US’ Southeast Asia policy.

Keep reading:

“The intention of Islam is to influence the whole world through rapid population” – As the Rohingya situation becomes ever more desperate, one man stands alone as their most vocal antagonist. Wirathu has been accused of using hate speech and acerbic propaganda to stoke anti-Muslim sentiment in Myanmar. Here, he tells Southeast Asia Globe that he is a man of peace who would show compassion if the Rohingya would only “be honest”