The New Masoeyein Monastery lies in a sun-drenched quarter of Mandalay, not far from the town’s busy jade market and the flat brown ribbon of the Irrawaddy River. The surrounding warren of backstreets echoes with the sound of chanting monks and distorted musical blasts from pagoda loudspeakers. Since it was founded in the 19th Century, this part of Mandalay has been a centre of Buddhist learning,a district where low-slung monasteries alternate with shimmering golden zedis converging skyward. It is in this tranquil setting, in a stuccoed monastery building, that Myanmar’s most notorious Buddhist monk presides.

Wirathu seems impatient. Since boatloads of Muslim Rohingya asylum seekers began their exodus from the coasts of western Myanmar in May, he has been inundated with visits from the international press. As the head of Myanmar’s 969 movement, an ultra-nationalist Buddhist organisation, Wirathu has been accused of fuelling the recent waves of violence against the country’s Muslims, and specifically against the Rohingya, a stateless ethnic group living in desperate conditions in western Rakhine State.

At one point in the middle of our hour-long interview, Wirathu complains that he has been misunderstood overseas. “The foreign media get information from the Muslim community and accuse me of fuelling violence through my preaching,” he says with the weary air of a man used to explaining himself over and over to uncomprehending outsiders. “My message is just to remind my followers.”

Otherwise, Wirathu seems to be enjoying the infamy and minor celebrity status that has come with being the head of the 969 movement. In his small audience hall, a wall is covered with newspaper clippings and large photographs of himself in various poses. The man who has been dubbed the “Buddhist Bin Laden” is pictured greeting supporters, standing by the seaside, posing with hands clasped angelically beneath his chin. Nearby, a painted portrait of the monk stares down over the worn wooden floorboards where I am directed to sit, like a novice, for my audience with the 969 leader.

When Wirathu emerges from a side-room, his flame-coloured robes sweeping the floor, I greet him to a shutter-burst from an assistant monk, who, camera-in hand, remains an unnerving presence throughout the encounter. (The photos will likely surface at some point on Wirathu’s busy Facebook page.) The 46-year-old Wirathu is unexpectedly short in person – barely five feet tall – but the deference of his orbiting assistants, and the awareness of the role he has played in Myanmar’s recent nationalistic resurgence, seem to add extra dimensions to his stature.

After an opening discussion of his upbringing in Kyaukse, a town in Myanmar’s dry central plain where he was born in 1968, Wirathu starts connecting the dots on what he sees as a worldwide Islamic conspiracy. “The intention of Islam is to influence the whole world through rapid population,” he declares by way of an introduction, propped up on a wooden chair from which he guides novice monks through the Buddhist dharma. “That’s their intention – to spread Islam around the world.”

Wirathu says he founded the 969 movement in 2001 to counter what he saw as an alarming increase in Myanmar’s Muslim population. “The specific thing is that this community is determined to swallow the Buddhist community,” he says. “Whenever a boy or a girl gets married to a Muslim, those people must convert to Islam.” Muslim men, he adds matter-of-factly, “get married with two or three wives, and every wife has to have children, sometimes women need to have a child every year… Every year their population is growing – they produce one village every year, even in small townships.” Without his efforts and those of his nationalist allies, Wirathu claims that “Myanmar might become a wholly Muslim country, like Pakistan or Bangladesh”.

Western journalists writing about Myanmar’s nationalist resurgence are forced to confront some ingrained clichés about the Buddhist creed. Seen from a certain angle, Wirathu, with his shaven head and saffron vestments, looks like a symbol of spiritual contemplation – a man of peace. But his movement’s message is strikingly at odds with the spiritual, elliptical tenets of Buddhism. Exhibit A is the 969’s theme song, a frighteningly catchy tune titled “Song to Whip Up Religious Blood”. Often played at rallies, the song’s lyrics describe unnamed outsiders who “live in our land, drink our water, and are ungrateful to us”, according to the New York Times. The chorus promises that “we will build a fence with our bones if necessary”. Wirathu has since urged his followers to boycott Muslim businesses – “Don’t let your money go to your enemy,” he said in a 2013 speech – and has called for laws to prevent inter-faith marriage.

For the man himself, of course, there is no contradiction. “I’m not a violent person,” he says, staring through reading glasses that give him a slightly schoolmarmish air, “but whenever I give a sermon I always talk about the abuse of women by the Muslims. So the Muslim community doesn’t like me. I assume that because of my preaching about the Muslim community the Muslims have a fear that other Buddhists will know their weaknesses. That’s why they accuse me of being a violent person, so the international community and the government put me under pressure.”

Though Wirathu has spent his entire adult life in the monkhood, it is unclear exactly how much he knows about Islam. Outside his audience hall stands a billboard covered with gruesome images of crimes supposedly committed by Muslims around the world. During our interview the monk reels off a long list of alleged Muslim atrocities – sexual abuse by imams in Rohingya camps, forced conversions of Buddhist women, violent attacks on Buddhist communities – but offers no hard evidence for most of his allegations. Most of them he reports hearing online, or gleaning second-hand during his travels around Myanmar. When pressed on his claim of an epidemic of rapes by Muslim men – a particular fixation – Wirathu admits: “I don’t have specific details on how many women face this kind of abuse,” and then simply repeats the claim, “but every town or city where Buddhist women get married to Muslim men, women have those kinds of experiences.”

Like many conspiracy theorists, Wirathu dwells long in the echo chambers of the web. More than 63,000 people follow his Facebook page, which offers a steady stream of 969 news and propaganda. He asserts that Muslims make up 22% of Myanmar’s population, more than four times the official figure, and even told the Democratic Voice of Burma that a Muslim cabal was behind a controversial 2013 Time cover story that dubbed him “The Face of Buddhist Terror”.

Wirathu’s critics argue that his sermons and social media postings were instrumental in the outbreak of violence between Buddhists and Muslims in Rakhine State in mid-2012, which eventually drove an estimated 140,000 Rohingya into internal displacement camps across the state. Though many Rohingya claim to have lived in Myanmar for generations, Wirathu regards them as a “fake” ethnicity, as “Bengalis” who have snuck over the border illegally from Bangladesh. He says the recent boat crisis erupted when the Myanmar authorities sealed the border with Bangladesh, forcing Bengali migrants to take to the seas. “Bangladesh is very small with 170 million people. Their only exit option is to enter Rakhine State, but now there are restrictions so that’s why they have left their country,” he says.

Wirathu says he would have some sympathy – and even provide humanitarian aid – if the boat people just “admitted” they weren’t from Myanmar. “If these people regard themselves as refugees I have sympathy and I want to show compassion and I’m ready to provide humanitarian assistance, but they need to be honest,” he says. “They say they come from Myanmar, and they say they are Rohingya. But actually they are Bengali.”

At the same time, Wirathu repeatedly denies that he has advocated violence, in Rakhine State or anywhere else, saying – again, without any real evidence – that Muslims were really to blame. “The violence happened because of the Muslims… Buddhists don’t like violence, and the government doesn’t like violence. Buddhists don’t need to fight back with violence. That’s why we try to protect [against] the threat of the Muslim community through official laws,” he says.

The laws in question are a Nuremberg-style package of Race and Religion Protection Laws, which, after a long campaign by Wirathu and his nationalist allies, were introduced in Myanmar’s parliament in November 2014. The first to be passed was the Population Control Healthcare Bill, signed into law in May. The bill contains a provision on “birth spacing”, which requires women to allow at least 36 months between children. Critics say the law is likely to be used to target Muslims, a motivation that Wirathu openly admits. “This is not targeted towards all people,” he says of the population bill. “The law will be used differently for those townships where there is rapid population of Muslims.” The other race and religion laws envision bans on inter-faith marriage and unauthorised religious conversions.

Wirathu now looms as a key player in the landmark national elections expected to take place in November. He says his movement won’t support any particular political party, but will support any candidate that pledges to “defend nationalism”. This is bad news for Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s longstanding icon of democratic values and head of the opposition National League for Democracy. Even though she has controversially remained silent about the Rohingya crisis, fearful of alienating Buddhist supporters, Wirathu sees her as a great disappointment: “Since the violence happened in Rakhine [in 2012] I have no longer supported Aung San Suu Kyi. She emphasised democracy, but not nationalism. In the violence in Rakhine, people were killed by Muslims. She needs to condemn this, but until now she is yet to give a comment on that.”

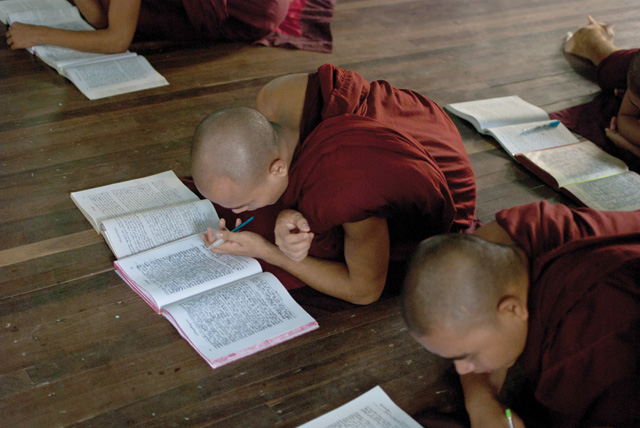

Just as Wirathu seems to be growing tired of the discussion, Buddhist novices begin filing into the hall for instruction, and he calls a sudden end to our interview. The students are all in their teens, in robes of a deep brownish red. They crouch down low on the worn floorboards, books of Buddhist sutras at the ready. A bell peals somewhere outside. Turning to his charges, Myanmar’s prophet of hate opens a thick book, chants and immerses himself in a philosophy of peace.