It’s no secret that the Stasi, one of the world’s most effective and repressive secret police agencies, had a thing for information. Its extensive network of spies documented almost every aspect of life in East Germany and infiltrated West Germany’s government and spy agencies. The communist intelligence agency’s net was cast far beyond the borders of Europe, with its tentacles reaching as far as Vietnam, its closest ally in Southeast Asia.

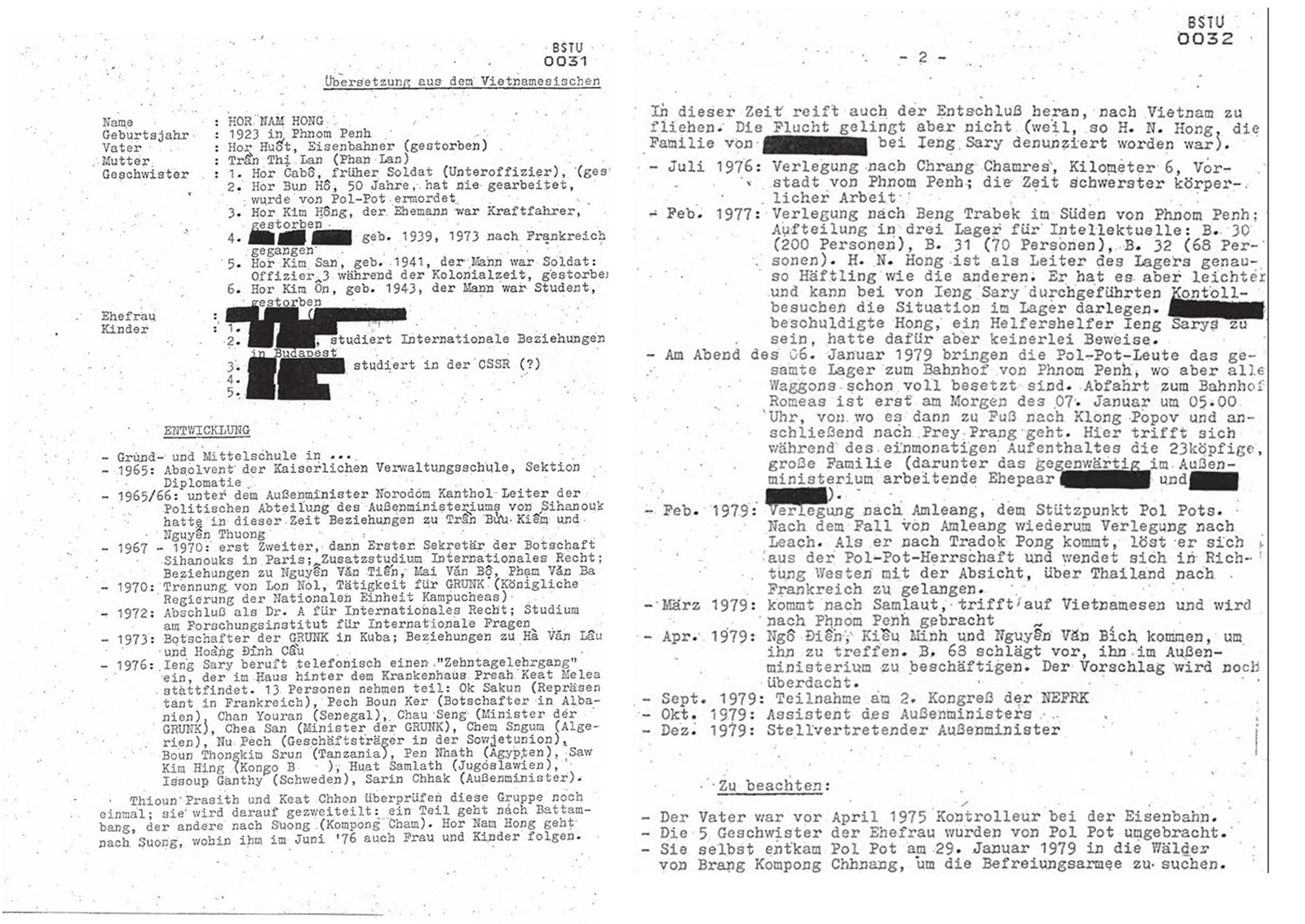

Buried in 111 kilometres of documents at the Stasi archive authority in Germany are dossiers written by Vietnamese officials about some members of Cambodia’s current ruling elite when they defected from the Khmer Rouge in the late 1970s.

North Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge were close allies until civil wars that wreaked havoc in their countries ended in 1975, after which point serious border disputes poisoned the relationship between the regimes. In Phnom Penh, Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot and his henchmen feared Vietnamese spies within their party and began purges in 1977. Numerous Khmer Rouge officers – including the current prime minister of Cambodia, Hun Sen – fled to Vietnam seeking a change of allegiance. Fearing counter-espionage, the Vietnamese detained them and for each officer prepared a dossier, in which they incorporated biographic details and personal assessments.

While Vietnamese intelligence may have been no match for its efficient and methodical East German counterpart, the communist brethren cooperated in various areas, including the exchange of information. Written between 1978 and 1979 and later translated into German once they were handed over to the Stasi, MfS – HA II Nr. 38135 includes assessments of people the Vietnamese would install in high-ranking positions in Cambodia, a country it ‘liberated’ from the Khmer Rouge and occupied in 1979.

There are few doubts about the veracity of the folder, which includes profiles of about 20 individuals and reveals unadorned views of some of those who would become Cambodia’s leaders. The dossier includes assessments of people who did not hold top positions after 1979 and of those who did for a short time only, such as Nou Beng (Minister of Health and Social Affairs in the 1980s and governor of Kratie province after 1993) and Khang Sarin (Minister of Interior from 1981 to 1986). Some of the people in the files have passed away: Sing Song, Minister for National Security for 14 months following his stint as Minister of Interior from 1988 to 1992, who died in 2000 and Chea Soth, Minister of Planning from 1981 to 1986, who enjoyed periods as deputy prime minister during the 1980s and was a member of parliament for four years prior to his death in 2012. Some of the files have been printed twice and others censored, some are thin with only one or two pages per person, while others comprise detailed profiles.

In general, the files appeal unsystematic – compiled from information amassed chaotically rather than methodically – and list the communist background of each person.

Similar to many of his fellow countrymen, Chea Sim – the current president of the Cambodian Senate and the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) – is described in a dossier as someone who hates Pol Pot and Ieng Sary (the late Khmer Rouge foreign minister), and has a strong will to topple the regime and rebuild Cambodia. While the author certifies that “comrade Xim demonstrates a morally good attitude towards the people”, he also states that he occasionally appears “conciliatory, craven and undecided”.

Som Rin is none other than Heng Samrin, who today chairs Cambodia’s National Assembly and who is honorary president of the CPP. When the Vietnamese wrote the dossier, Heng Samrin and Chea Sim led the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation, which was founded in December 1978. After the fall of the Pol Pot regime, Heng Samrin was promoted to chairman of the People’s Revolutionary Council of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea in 1979 and chairman of the Council of State and secretary-general of the People’s Revolutionary Party two years later. Born as Heng Him in 1934, under Pol Pot he was commander of a military division – one of the highest positions held by all of those who fled the Khmer Rouge.

“He is a sincere man and honoured by many cadres due to his comprehension,” the dossier said of Heng Him. However, “[he] has a low education, does not talk a lot and sometimes he has an inferiority complex… his political understanding is limited”. The file finishes with the remark that “Rin” can absorb higher tasks once he has completed further education. From the vantage point of the present, one can only assume that Heng Samrin was successful in doing that.

Others were not so fortunate. Pen Sovan, Cambodia’s first prime minister after Pol Pot, was sacked after five months on the job and imprisoned in Vietnam for more than ten years. However, Pen Sovan’s file does not reveal any hint of reservation about him or any expectation of dissent.

In contrast, the file on Hor Nam Hong, who has been Cambodia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs for 15 years, discloses evidence that sheds light on a historic dispute regarding his role during the Pol Pot regime. Current opposition leader Sam Rainsy, who has been in self-imposed exile for more than three years, has maintained that Hor Nam Hong was the director of a prison during the Khmer Rouge period – a claim the minister has always rejected, asserting that he was only a common prisoner. According to the dossier, in 1977 Hor Nam Hong was interned in the Boeung Trabek re-education centre – a Khmer Rouge prison for former diplomats called back by the new government after April 1975.

There are few doubts about the veracity of the folder

Markus Karbaum, Southeast Asia Studies consultant and lecturer, Free University Berlin

“As the director of the camp, H. N. Hong is just the same prisoner as the others. However, it is easier for him and he can present the situation in the camp to Ieng Sary during his inspections,” the dossier reads.

Bou Thong, deputy prime minister in the 1980s, is described as “intelligent, inventive at work, resolute with good organisational skills”, while his “undemocratic behaviour” and “false ambition” are noted as weaknesses.

The dossier on Cambodia’s long-serving prime minister Hun Sen reveals that his “correct name is Hun Bonal. When he came to Vietnam, he called himself Hai Phúc.” In Hun Sen: Strongman of Cambodia, authors Harish C. Mehta and Julie B. Metha quote Hun Sen as saying the following in 1997: “I had to disguise myself as a person from Laos… They gave my name as Mai Phuc (meaning happiness forever), aged 26, a high-ranking cadre from Region X.” The reason cited for the new identity was to not “attract attention or give rise to suspicion”. As the book is based on statements made by Hun Sen that were not verified, this explanation for his name change can be questioned.

A commander by age 26, Hun Sen had an extraordinary military career. Three months after his escape to Vietnam in June 1977, Cambodia launched a vicious attack on the Vietnamese city of Tây Ninh, deeply straining relations with Vietnam. Perhaps it was for this reason that Hun Sen did not wish to be identified as a former commander of a Cambodian regiment that had nearly 2,000 soldiers along the border. However, Hai Phúc is neither a Laotian or Khmer name, but instead Vietnamese. Is it possible that Hun Sen wanted to demonstrate solidarity with his new allies by changing his name according to their language?

The dossier also addresses Hun Sen’s family background. Following his escape to Vietnam, Hun Sen was separated from his wife Bun Rany (born Sam Heang). A few days after she had given birth to their second child, Bun Rany, as the wife of a deserter, was taken into Khmer Rouge custody. Prior to their reunion in Phnom Penh in February 1979, both had received a message that the other was dead and Hun Sen had been introduced to a young woman whom he wanted to marry. The dossier says: “However, when his wife (Bun Rany) came back, he broke off with her resolutely and took her… to the Embassy of Kampuchea in Hanoi.”

While the Stasi archives centre has blacked out the name of the woman to protect her personal rights, the German documentation centre – through these dossiers – has once again shed light on the secret communist world prior to 1989.