There is little wonder why ancient humans gave prophetic qualities to the animal kingdom. Long before the days of computerised climate models and long term weather forecasting, animals were the nearest thing they had to an early warning system of seasonal arrivals, impending disasters, and environmental change.

They were the original canaries in the coalmine, as it were. Some of those beliefs still find currency today; in the naming of lunar years for example, or in the time-honoured Royal Ploughing Ceremony that precedes each seed-sowing season in Cambodia.

Given the kinship that the rural population shares with the natural environment and a healthy dose of superstition, it is understandable that Cambodian farmers were probably far more interested in what the royal oxen had to predict for the coming harvest, than in the dire warnings of global peril released in a 2007 report by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The news was not good from either oracle. When the two royal oxen were offered the seven golden trays of different food and drink, only one of them ate, and it chose corn – not a good omen. Of course if the royal oxen had really had their prophetic heads screwed on properly and were able to see, not just one, but ten or twenty years into the future, they would have acted quite differently.

They would have ignored all the trays, corn included, and would have begun walking, and they would have kept on walking as far away from the Mekong Basin, the Tonle Sap Lake, and its catchment area as they could. They would have made for higher ground, and in the not too distant future it is certain that other denizens of Cambodia’s vast riverine plains will also make a retreat from areas that are no longer able to support them, either because of excessive water or too limited food.

They will join millions of others presently living in river deltas, coastal zones and small islands around the world, as some of the first, and the most unfortunate, victims of climate change. The consequent shifts of people and habitats could lead to severe repercussions as ‘envirogees’ – victims not of oppressive governments, but of insupportable climatic conditions – would have to be accommodated; and, as bona fide citizens, envirogees will be expecting somewhere to live.

Climate evolution

In one sense climate change can be thought of as climate evolution, but it is an evolution in which man has unwittingly found himself with his hand at the throttle. We owe our existence to the greenhouse effect – the retention of certain gases in the atmosphere that act as a one way filter for light energy, holding in heat.

This ensures that the average surface temperature of Earth remains around 15C, and can support life; unlike that of the atmospherically devoid moon – a similar distance from the sun – which stands at -18C. The atmosphere of Earth also provides carbon dioxide (CO2) for plant photosynthesis, and oxygen (O2) for animal and human respiration.

Man’s initial impact on the climate began around 6,000 years ago with the clearing and burning of forests to begin the first arable farming. It took another step forward with the large-scale cultivation of rice paddies, which produce methane (CH4), the second largest cause of global warming.

Since the industrial revolution some 200 years ago, things have stepped up apace, human activities have released excessive amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, mainly through the burning of fossil fuels, and greatly accelerated the natural course of warming. Global surface temperature has risen by 0.5C in the past 100 years and is expected to rise by another 2C in the next 100.

If 2C does not sound like much, it is worthwhile remembering that only 5C separates us from the last ice age. The global mean sea level has risen by 10 to 20cm in the past century – roughly ten times the average rise of the past 2,000 years.

As the planet warms, and oceans expand, both from melting glaciers and thermal expansion caused by a rising sea temperature, flooding in coastal areas will rise dramatically. Climate change affects the Earth’s hydrological cycle causing changes in precipitation patterns. This will change flood and drought frequency, intensity, and duration. Seasonal pattern changes will threaten water supplies, crop yields, animals, plants and ecosystems that rely on a natural balance for survival.

The prediction for Cambodia is that the rainy season will be shorter and more intense, and the dry season will be drier and longer. A study by the Cambodian Ministry of the Environment in 2001 suggested that by 2100 rainfall will increase by up to 35% and the temperature will rise by between 1.3C and 2.5C.

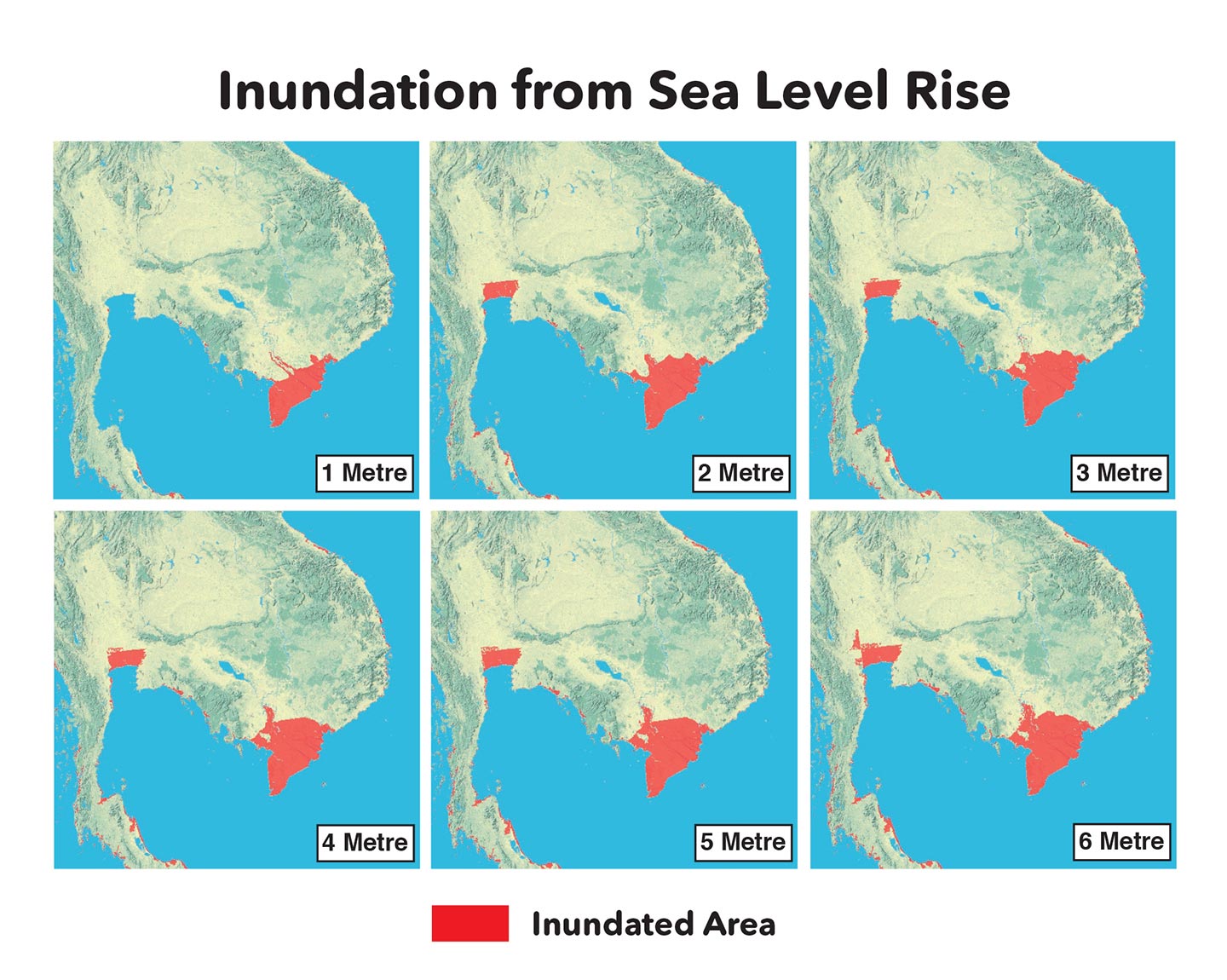

A warmer ocean will also lead to increasingly extreme and more frequent hurricanes and cyclones, causing storm surges to threaten low lying coastlines and islands. In many ways Cambodia is fortunate in that it has a relatively short coastline and is protected from the worst cyclones by its geography. However, a 1m rise in sea level would still flood many coastal areas, especially in Koh Kong province.

This is the main issue for the next 10-20 years, if sea levels rise as predicted. There will be little evidence of sea level rise [in Cambodia] except during flooding events, with high tides, linked to typhoons. The combination could lead to catastrophic flooding

Bernard O’Callaghan of the World Conservation Union in Vietnam

Koh Kong city, for example, would permanently lose over 44 km2 to the sea. If cyclones were combined with heavy rainfall, either on the coast, in the Mekong catchment area, or in the Tonle Sap basin, things could become rapidly more perilous.

Bernard O’Callaghan of the World Conservation Union (IUCN) in Vietnam says, “This is the main issue for the next 10-20 years, if sea levels rise as predicted. There will be little evidence of sea level rise [in Cambodia] except during flooding events, with high tides, linked to typhoons. The combination could lead to catastrophic flooding.”

Sinking feeling

Around the world, 634 million people – about a tenth of the global population – live in coastal areas that lie within 10m of sea level. About 75% of those areas are in Asia. Bangkok only lies 1m above sea level and is sinking into its soft, loamy soil at a rate of 10cm a year – a situation exacerbated by the excessive pumping of groundwater to satiate an ever-growing population.

In Phnom Penh, Chattomukh – ‘the four faces’ – lies at the confluence of Cambodia’s four great rivers, the upper Mekong, Tonle Sap, lower Mekong and the Tonle Bassac. Phnom Penh was described by renowned architect Vann Molyvan as “an active sedimentation zone with poor ventilation and prone to flooding”.

The water level of the Tonle Sap rises each year as the Mekong, unable to discharge its floodwaters, reverses the flow of the Tonle Sap river and sends water into Cambodia’s great lake, the Tonle Sap, increasing its volume from 3,000 km2 at a depth of 1m, to 10,000 km2 at a depth of 10m, inundating adjacent land for up to 5 months.

When the Mekong relents (usually in October) the Tonle Sap reverses flow and drains the floodwater back to the Mekong. Despite some improvements in 2003, Phnom Penh’s drainage and sewerage system (they are one and the same) looks ill equipped to cope with predicted flooding. Nor does the filling in of the city’s ‘boengs’ (lakes) bode well for future flood management.

There is also the very real possibility that the IPCC figures are an underestimation, as Minh Cuong Le Quan, manager of the climate change unit of renewable energy and environmental group, Geres (Cambodia) points out.

“The change is predictable, the thresholds are not,” he says.

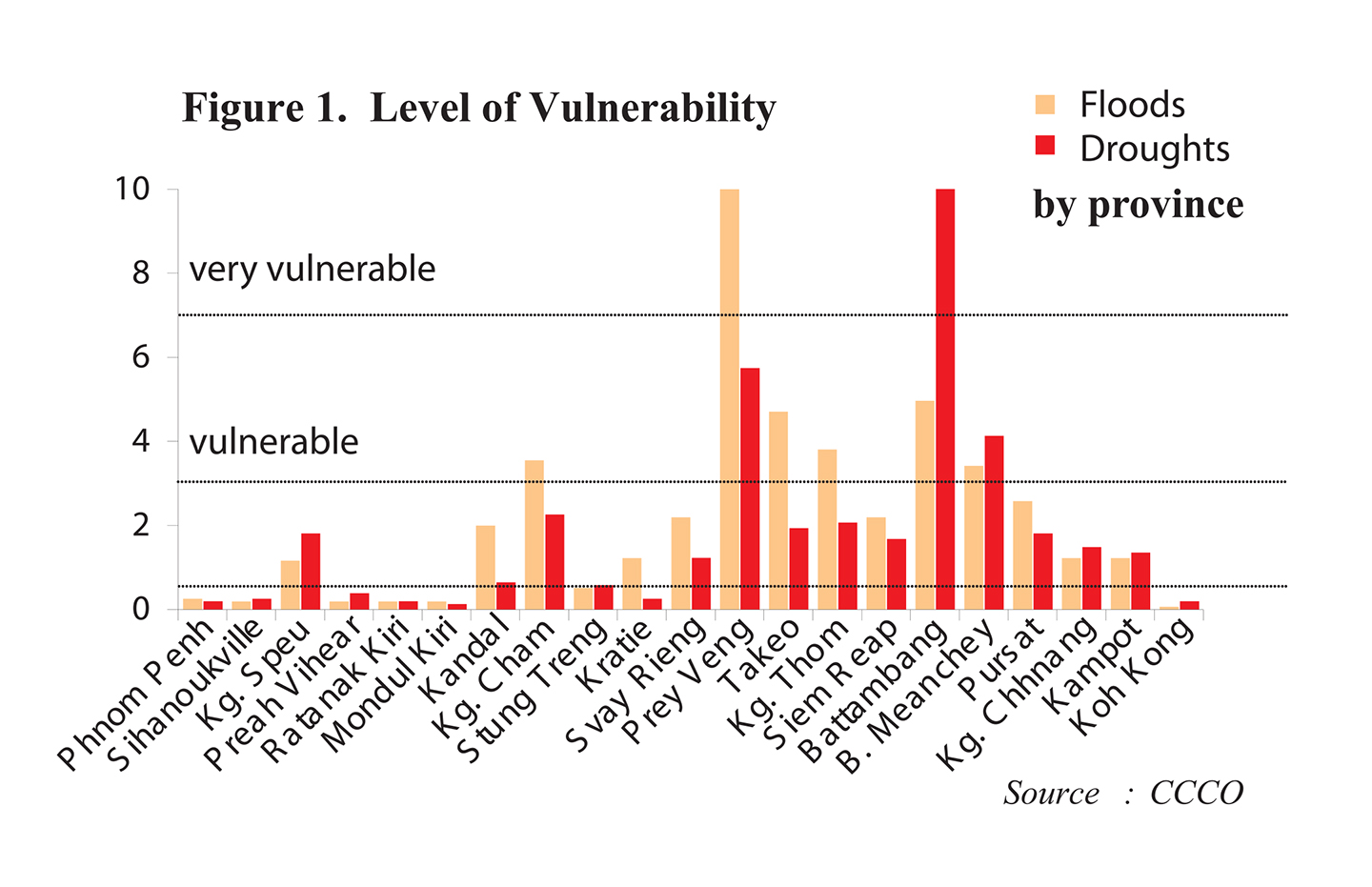

Something of that unpredictability is already apparent in the changing patterns of the weather. In 2000, the rains arrived in Cambodia 45 days before the scheduled start of the monsoon. Floodwaters submerged 400,000ha of cropland affecting 22 of 24 provinces. Three hundred and forty-seven were killed – 80% of who were children – and emergency food supplies were distributed to 1.4 million people.

In 2001 further flooding took 29 lives and caused $12 million of damage. In 2003 and 2004, the rains abated for the most part, only to be replaced by drought. In 2005, the floods returned, affecting 275,000 people, mainly in Stung Treng, Kratie, Kompong Cham and Kandal.

Similar extreme climate events were repeated throughout Asia. Between 1994 and 2004, about one third of the 1,562 flood disasters, half of the 120,000 killed, and 98% of the 2 million affected by flood disasters were in Asia. Conventional wisdom states that Cambodia can expect one ‘super flood’ every 70 years, but the increased frequency and repetition of flood and drought can have a similarly destructive effect.

EDITOR’S NOTE

It’s 2020, and over a decade has elapsed since the foreboding predictions in this article were first published. Unsurprisingly, the messages imparted remain hugely relevant today, and are imbued with just that little bit more urgency as the clock ticks down before Southeast Asia reaches an environmental tipping point of no return.

In Cambodia, extended droughts in 2019 caused by El Niño resulted in the tributaries of the Tonle Sap drying up, as well as the lowest water levels on the Mekong River in a decade. This spelled disaster for many of the Kingdom’s farmers and fisherman last year.

“I am facing starvation and [I am being supported by] my children. They shipped me some rice and I distributed some [of that] to other fishermen,” an impacted villager told RFA’s Khmer Service in July.

Region-wide, current predictions show that Southeast Asia is set to be hit hardest globally by rising sea levels in the coming years. Much of the Greater Mekong Subregion is under threat of being submerged in the coming decades, and in October, new projections showed that 150 million people – the majority in Southeast Asia, and some in Cambodia – are living on land that will be below the high-tide line by 2050. Southern Vietnam, including Ho Chi Minh city, may all but disappear if these predictions are accurate.

As Minh says, “The period between 2003 and 2005 were three of the hardest years for Cambodian farmers. It successively increased their vulnerability, many farmers decapitalised – that is, they began selling land, stock or their own labour to provide for their livelihoods.”

Many commentators have indicated that the brutal irony of climate change is that, in the short term, it affects those least able to cope and is in part caused by those who appear best insulated from its effects.

However, even the assumption of the Western world’s readiness may prove to be yet another fallacy ready for debunking. “Yes, extreme events hit the poor hardest but look at how even a richer country like the US couldn’t cope with hurricane Katrina,” says Minh.

While tsunami-like images of waves engulfing whole communities are a dramatic vision of climate change, its real damage to Cambodia’s way of life could be much more insidious.

“Local people in the area of the delta are already reporting some changes. These include increased erosion, salinisation of the inland waterways and fruit trees that are not fruiting in the ‘normal’ way, such as fruit lacking seed etc.

As there is more change in the climate, there will be changes in habitats, especially among the plant communities. This will result in changes in birds, fish and insect communities. “This will be relatively gradual, but there will be a major change over time,” says O’Callaghan.

Animal species have different capacities to respond – some can migrate, provided there are continuous relatively undisturbed ecosystems available for them. In Cambodia they say, “teuk trojek, trey kom” – “if the water is cool, fish will gather” – which suggests that the fish are going to be gathering less and less.

For convenience fish in Cambodia are categorised as ‘white’ migratory fish, which rely upon different habitats at each point in their life cycle and face the biggest struggle to adapt; and ‘black’ fish, which live in the floodplains and which may also struggle with rising water temperature, reduced oxygen, and the possible absence of water altogether.

Up until now the main problems facing rice farmers have been flooding, drought and the persistent use of banned pesticides. Over 80% of the rice grown in Cambodia is rain-fed, the timing of sowing and the life cycle of the crop are at the mercy of the weather. A seasonal shift and changes of precipitation will affect soil quality, crop yield and life cycle.

Farmers may well find that varieties of rice grown now are no longer suitable, and will have to be replaced by salt- or drought-resistant hybrids. There is also the likelihood that vector born diseases, such as malaria or dengue will increase in both geographical range and intensity.

The Cambodian Climate Change office was established in 2003 to address the climate hazards facing Cambodia and to prepare strategies to deal with them in the long and the short term. They are also actively engaged in the assessment of new technologies to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

As Minh at Geres observes, “First you must have mitigation then learn to adapt.” By using the guidelines of the Kyoto Protocol, Cambodia can benefit from the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which allows developed countries to finance carbon saving schemes in developing nations and thereby reduce their ‘historical debt’ to the environment.

Everyone can help, simply by switching an A/C to dry will save 75% of the power. Using fluorescent bulbs instead of incandescent will cut consumption by a half

Minh Cuong Le Quan, manager of the climate change unit of renewable energy and environmental group Geres (Cambodia)

Minh is in no doubt about the need for immediate action, “Of eight billion tonnes of CO2 released into the atmosphere, the Earth only cleans 3.3 billion. The rest is added to the historical surplus. We must reduce our consumption, starting right now.

“CDM is a good reason to switch from coal to gas power generation. It is also a good way to encourage small sustainable businesses to develop. But everyone can help, simply by switching an A/C to dry will save 75% of the power. Using fluorescent bulbs instead of incandescent will cut consumption by a half.”

Geres recently launched the Cambodia Carbon Facility to help establish carbon saving projects and evaluation schemes in the private sector. Geres have already entered this market and made a substantial difference to the amount of energy being used every time a wood stove is lit. So far, 230,000 specially insulated cooking stoves – which are three times as efficient as traditional stoves – are being used by 180,000 families.

“With better stoves and better charcoal making we could cut the amount of charcoal used by half,” says Minh. Instead of using older forested trees Minh suggests that thin fast-growing varieties should be planted to increase fuel efficiency and retain what remains of Cambodia’s natural forest. It is a new approach for Cambodia and the idea of a carbon market is still in its infancy.

“Many of the measures taken today, will not bear fruit for 50 years,” says Minh. The Mekong river delta is similar to other river deltas around the world in that, more than any other land feature, it is created and continuously recreated by the environment, and the governing climate of the time.

It changes every day. In 50 years the Mekong delta, and many other parts of the world will look very different. People will have to learn to adapt to this new terrain to ensure that the planet as a whole, and the area of the Mekong delta in particular, will still hold sustainable life.