Gabrielle See is a senior at Singapore Management University studying Politics, Law and Economics. She has written for the Journal of International and Public Affairs and Social Space Magazine. While the Globe takes the utmost care to publish accurate information, by the nature of these first-hand accounts we are unable to independently verify the accuracy of the details contained within them.

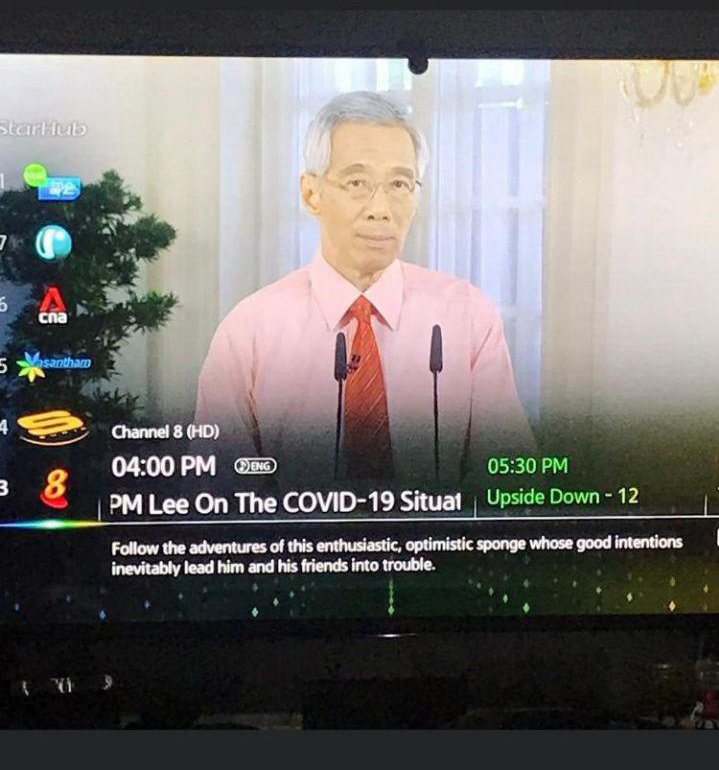

It’s 4pm on April 3 – my mother and I tune in to catch Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s address to Singapore regarding the Covid-19 situation.

Less than an hour before his address, my mother had forwarded to our family’s Whatsapp group chat what appears to be a document by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) regarding the closure of schools, to which my father replied (as anyone who receives such unverified news should), “Do not forward without verifying the source. It is good to hear from PM himself at 4pm.”

A slightly frail-looking PM Lee (I suspect because of improperly done white balance) appears on screen in his signature pink button-up shirt, “my fellow Singaporeans…” he begins, and continues to explain in soothing and measured tones why much stricter measures in the form of a “circuit breaker” are needed in the month ahead.

Also, someone in charge of programming seems to have forgotten to update the caption for Lee’s speech, which gave Singaporeans a good laugh amid a rather tense situation.

We were initially told schools and non-essential businesses were to be closed from April 7 until May 4, confirming the contents of the aforementioned document which made its rounds on Whatsapp – the public servant and her husband who were responsible for leaking and circulating it have since been arrested under the Official Secrets Act. We are told to stay home as much as possible, only going out for essential things and to avoid socialising with people outside our household.

Despite the government steering clear away from the use of the term “lockdown” (though the measures do seem akin to those in a partial lockdown) most Singaporeans have nonetheless taken away from the PM’s address that’s what we are going into.

Many even inferred from the PM’s tie color that the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (Dorscon) level has been raised to red – the highest level – though for now, it just remains an unfortunate wardrobe choice.

My university classes had mostly been moved online by the time these new measures were announced so life wasn’t too different, apart from the fact that I now help to take care of a newborn in the day as well. (Not mine!) In the midst of all this chaos, my sister-in-law has given birth to my niece. Thus, the recent “circuit breaker” measures have been much welcome, as the whole family is now home to share the burden (and joy!) of caring for her.

My sister-in-law’s measly maternity leave – a maximum of 28 days as a student teacher under National Institute of Education (NIE) rules, in contrast to the 16 weeks at other workplaces – essentially got extended a little.

Meanwhile, my older brother, who was halfway into his teaching practicum, does not have to go to the school he teaches in for the rest of the practicum, meaning he can spend more time with his daughter beyond his precious two weeks of paternity leave. There’s also my younger brother – who is currently awaiting his enrolment into university – and parents who are working from home.

However, I’m keenly aware that it’s a privilege to be able to adapt swiftly to these measures, much less find them beneficial, while others fear that they would not be able to sustain enough income to fulfil their caregiving responsibilities. It also feels jarring to read about cases where coronavirus lockdowns seem more like captivity for some, with more occurrences of domestic violence and discrimination faced by young LGBTQ people from their family.

If the ability to adapt to a lockdown could be put on a scale, it would probably be low-wage foreign workers at the far end of the spectrum, followed by the homeless. Then those who technically have a roof over their heads but don’t truly feel at home, middle-class families like mine, and finally on the other end of the spectrum, the wealthy represented by celebrities who make “relatable” Tik Tok videos about the anxiety they are experiencing as they social distance in their luxurious homes.

While the coronavirus knows no socioeconomic boundaries, the already vulnerable and marginalised in society bear disproportionate risk of getting infected.

The day after the PM’s address, we learnt that new virus clusters have formed in foreign worker dormitories in Singapore, requiring about 20,000 workers to be quarantined in their rooms for two weeks in less than ideal living conditions.

The news weighed heavily on my heart – how up until now, the needs of this group of people have been overlooked and how alone those tested positive for Covid-19 in a foreign land must feel without their loved ones by their side.

The next day, I brought up these thoughts at the dinner table to my family members – nowadays the sole audience of my rants. But my father countered that these construction companies work on tight budgets as they only get projects by bidding the lowest for them (echoing Manpower Minister Josephine Teo’s sentiments, “Are people prepared to pay more?”).

Can we really expect employers to house these workers in single rooms, he asked? My father goes on to quip about the hardships he had to endure as a teen when he used to work as a construction worker, “I know how tough their life can be. My whole body used to ache, even until the next day!”

His words made me recall Teo You Yenn’s writing in her seminal work This is What Inequality Looks Like: “These quips render the speakers dignified rather than ashamed because their internal narratives are of progress, about overcoming hardship and ultimate triumph”.

People like my father who have long relegated their poorer living standards to things of the past, do this to soften the blow to Singaporean national narratives of success bought by hard work, which trouble their personal narratives and feelings of deservedness.

Two weeks into the “circuit breaker” period, PM Lee addressed the nation for a second time on April 21 to provide a rather grim update about the Covid-19 situation. It looked like PM Lee had learnt from his unwise choice of shirt and tie colour the last time round and donned a colour outside of the Dorscon spectrum – no room for speculation there.

He announced that “circuit breaker” measures have been further tightened and extended. My family looked at each other incredulously as we heard the news and my dad had to clarify whether he had heard correctly, “Wait how many more weeks? Four more weeks?”

Among the businesses further slated to be closed from the day after until at least May 4 are standalone food-and-beverage outlets that only sell beverages, confectioneries or desserts. To celebrate my niece’s first full month (known as ‘man yue’ in Chinese tradition), we had planned on ordering some dessert and pastries to commemorate the day at home. That was no longer possible, so we decided to bake the goods ourselves instead.

In other words, our family is among the privileged ones that are adapting well – where we are even thankful for the time these measures have bought for us to look after my niece and embark on cooking projects together.

It looked like PM Lee had learnt from his unwise choice of shirt and tie colour the last time round and donned a colour outside of the Dorscon spectrum – no room for speculation there

But conversations at our dinner table continue to bring up the divergent views we hold according to our age group. My parents are of the view that the number of rising cases in dormitories can be mostly attributed to the individual actions of the low-wage foreign workers. They bring up how they tend to socialise a lot on their days off, and my dad even mentioned that the shophouse building along 234 Balestier Road linked to these workers included budget hotels, suggesting some hanky-panky might have gone on and resulted in a further spread.

They also frequently update us (almost gleefully) with the new cases they have read about in the news or their Whatsapp group chats of Singaporeans flouting safe-distancing rules and what a disgrace they are to society.

Meanwhile, my siblings, including my sister-in-law, speak more critically of the state and how the spike in the number of cases in foreign worker dormitories could have been foreseen. She points to advocacy groups like Transient Workers Count Too and Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics, which have been sounding the alarm for over a decade about the cramped living conditions low-wage foreign workers are subjected to and the poor nutrition they get, putting them at higher risk of infections like chickenpox, dengue fever and Zika.

Sometimes, the conversations threaten to grow into heated debates and I have to fight back the urge to just go “OK boomer” to dismiss my parents’ views. But I would say such civil disagreements are the closest to any strain in relationships we have experienced, and not worthy of comparison to the pain and suffering those with already fragile relationships have to work through during this period of time.

As of April 24, the total number of dormitories gazetted as isolation areas has increased from two to 25. Singapore has surpassed 13,000 total Covid-19 cases and now has the highest recorded number in Southeast Asia. Unfortunately, rather than noticing cracks that are showing in our system, Singaporeans (like my parents!) seem to be revelling in the culture of ‘snitching’. Facebook groups like “SG Covidiots” have been formed to facilitate that, egged on by mainstream media outlets constantly running stories about people being charged for flouting safe-distancing measures, as well as a Singapore government app that allows you to report such cases.

As a nation, rather than embodying the qualities of unity, resilience and solidarity (the values our stimulus packages are named after), the pandemic seems to have turned us against each other – keeping us from seeing the deeper structural problems that reveal how certain vulnerabilities that have existed long before the outbreak are manifesting themselves now.

So as the daily flow of life for Singaporeans gets interrupted under “circuit breaker” measures, I’m hoping we will all continue to do our part to practice safe-distancing. But more than that, let us focus our time and effort not into the mutually-destructive act of pointing our fingers at the handful of “SG Covidiots” and the individual attributes and behaviours of foreign workers.

Instead, let us consider how we can be practicing mutual aid while examining the faulty systems the Covid-19 outbreak has brought to light, and how we would like to fix them in a post-pandemic world.

This story is part of the Globe’s Tales of the Pandemic series, a collection of personal essays from across Southeast Asia called published each Monday covering different aspects of life during this unprecedented time in human history. All of these Covid-19 stories can be found here. If you’d like to contribute a personal essay of your own, please email your story of roughly 1,000 words to a.mccready@globemediaasia.com.