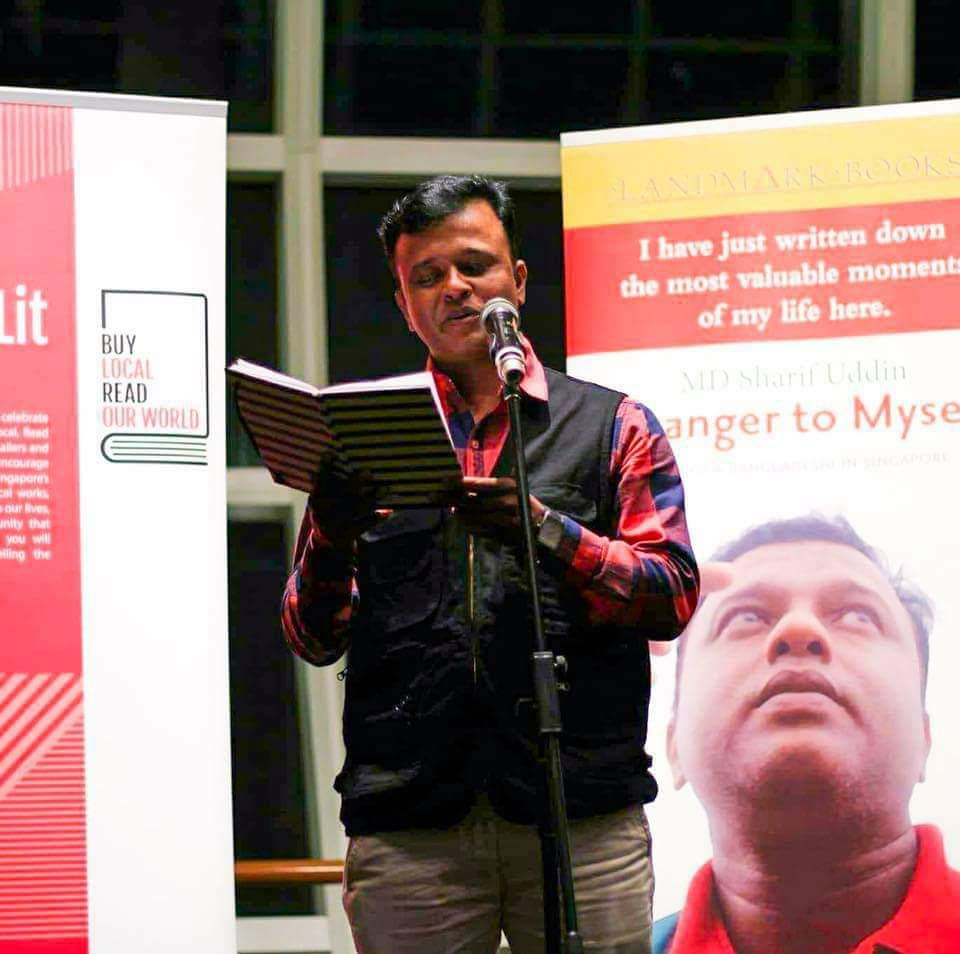

Md Sharif Uddin is a writer and migrant worker from Bangladesh. His collection of diary entries and poems, Stranger to Myself, chronicles the heartache, burdens and memories of his time working in Singapore, winning best non-fiction title in the 2018 Singapore Book Awards. He also participated in the Singapore Writers Festival in 2017 and 2018, and the 2018 Singapore Poetry Festival.

This is Md’s account of life under lockdown after several dormitories housing almost 20,000 foreign workers were isolated on April 5 as part of Singapore’s ongoing “circuit breaker” month to control the spread of Covid-19. Confining these men to their dorms for at least 14 days, the move has prompted criticism about living conditions for migrant workers, forcing Singapore to confront how it treats the people who build the city-state.

Additional reporting and editing by Toh Ee Ming

I first came to Singapore in the year 2008 and joined a company for the third time in 2013. After almost seven years, last December, the company cancelled my work permit on sudden notice and sent me back to my country. I was flying back to my home with a heavy heart to a life of uncertainty, leaving behind Singapore, the tiny city of dreams.

Shortly after arriving in Bangladesh, I began to hear bad news that the outbreak of novel coronavirus had begun in several countries. People were so confused and the news of deaths shocked everyone.

I was worried about my future – the invisible coronavirus was destroying my dreams. The nights were deep but I could barely sleep. The gentle hand of my partner would touch my hand, take my head to her heart as I fell asleep at night.

People started to realise that an invisible threat was coming towards all human life on Earth. While people started to stick together with their beloved ones and families, I was planning to return to Singapore again. And I did, with a dream in my eyes and the pain of leaving my wife, my brothers and sisters back there.

My dream was simple – to create a better career in Singapore this time. I joined a company as a safety coordinator last month in March, it was a good start, but my luck was not favourable!

The invasion of the invisible enemy called novel coronavirus had just begun all over the world. Every day I heard the news of death and I was horrified to see scary pictures every day. Maybe the world is taking revenge for our sins and healing itself, I thought.

The number of victims was also increasing, with the beauty queen of Singapore becoming a place without tourists. There was a radical change in everyday life and we started to hear the mourning on the canvas of life. More migrant workers, as well as locals, started to get infected. Death began.

The Singapore government said that no expatriate should leave the country at this time and those who have already left the country should not come back in. When the government could not stop the number of infected cases, even by putting in place new laws, the task force team declared a ‘circuit breaker’ where stronger social distancing measures would be enforced.

The circuit breaker began on April 7, creating a huge barrier to the migrant workers’ future plans. Everything was going wrong.

I look upon the open sky. Emptiness swallows me, my loneliness increasing with the silence of the night. I am tired of stumbling. Now here with no work, no money – not having money means the pace of my life has stopped.

Uncertainty seems to be on my mind again. I try to find shelter in my diary again as I write down the feelings that I can barely express.

The circuit breaker means a new chapter, a new experience in our lives. Thousands of workers are crying as they face a distressed life, confined to their dormitories. There are so many restrictions to protect ourselves! Don’t touch this, don’t go there, don’t sit there. The government became so desperate to enforce the law – that is to protect yourself first and ensure the survival of others.

Then you may or may not think about your job and money.

Every day I double check my body temperature with fear. I go to sleep apologising to God. My body lays down on the bed but I can barely sleep. I wish I could go back to my family right now!

Humans are social beings, so this sudden isolation is a drastic change to human life. Every morning, my body wakes up but my mind is restless, so I try to lay down again. There is a pin drop silence around the city but a few days ago, it used to be a different picture.

Before, there would be a rush among the workers at this time to go to work. A long queue in the bathroom to get ready for work, then the lorry would come to take us. Today, it’s nothing but a pin drop silence. Everybody is awake, their eyes are empty. Behind their eyes, lies the tension of an uncertain future. How can you get rid of the financial problems if we stay inactive like this, month after month?

How could migrant workers possibly be safe when we are living so differently from ordinary citizens! Many companies use lorries to ferry workers to their workplace. It is obvious that we can be infected easily when we are seated so close

We are now experiencing a miraculous unrest, in bodies that used to be tired and used to hope for some rest.

Despite being superior creations by God, we are helpless now, defeated today by a tiny virus. An invisible force has created a wall among us. Panic is ever constant.

Many people are reporting over the phone that many problems are arising in their dormitory. Problems with moving, problems with living, with eating because it’s been prohibited to go out of many dormitories.

At night, we are shocked to see the updates of the rising Covid-19 cases. The number of infected migrant workers is increasing. It’s obvious, I think, how could we possibly be safe when we are living so differently from that of ordinary citizens! Many companies use lorries to ferry workers to their workplace. It is obvious that we can be infected easily in the lorries when we are seated so close in a crowded space.

The government should rethink this problem as soon as the outbreak is over.

I live in the same room with seven more people of different ages, migrant workers from Bangladesh, India and China.

Everybody has their own problems. The Chinese man in particular, made me suffer a lot because of his shortness in the ear. He is 62 years old. Although his two children are grown up and live separately from the family, he has to send them money every month. He also wastes a large portion of his income on drinking and in the casinos. If I ask him something, he looks at me like a child. Dreamless, he doesn’t know what to do with life.

We, the migrant workers, have received a long-term lock down declared by the government, but we, the low earning people, don’t know how to cope with the situation. We repeatedly ponder over these questions in our minds: will the respected and lord-like owners of our companies be with us in our miserable time? Will they compensate us financially? Everyone is counting the days but with little hope.

The migrant workers who get higher salaries are likely to be safer – they accepted the closure and are treating it like a holiday. The virus attack does not appear to be a big deal for them, maybe they are taking it lightly. They have stocked enough food, so they do not feel the pressure to buy extra food. They are enjoying the time watching movies and feeling amused, they are indifferent.

But many others didn’t get their monthly salary, so they have had to keep themselves under control. They eat oily foods catered for them. Some Indian youth drink alcohol in the evening and lie down, like life is rolling around in a whirlwind!

Migrant workers usually come from middle-class families, therefore the calculation of their lives is also tied to a mathematical formula. For the Bangladeshi and Indian workers, who are the only source of income for their families, if they stop sending money it means disaster for their family. They get into trouble for the debts at a compounded rate, because many migrants take loans from various NGOs or banks for various reasons in their country.

So, at the beginning of the month, the workers have to pay instalments on their loans to those places. Maybe by this month, all the calculations will go wrong. Maybe their family will get into trouble. Maybe those companies will give them trouble. I do not know how much more suffering is waiting for us migrants.

Many of us are practicing religious prayers in the common areas of the dormitories. There are some praying who I have never seen pray to God before. The fear of death has risen – as the effects of the virus rise in their own country, they can’t possibly stay strong.

They are frequently calling their families using the free Wi-Fi, many are talking emotionally in a video call. I have to see my children’s tense faces everyday. I wish I could hold them in my arms and kiss them on their forehead – how long has it been since they call me ‘Baba’, holding my arms!

I believe that this quarantine will be over soon and the coronavirus will go away. All sins will be washed away from the earth and nature will forgive us.

We, the migrant workers, will once again embrace this dream city. Only these days, these saddest of times – this wound will remain in our hearts forever.

This story is part of the Globe’s collection of personal essays from across Southeast Asia called Tales of the Pandemic. Published each Monday and covering different aspects of life during this unprecedented time in human history, all of these Covid-19 stories can be found here. If you’d like to contribute a personal essay of your own, please email your story of roughly 1,000 words, preferably with images, to a.mccready@globemediaasia.com with the subject “Covid-19 personal essay”.