Outside Phnom Penh’s National Museum on an afternoon in mid-April, temperatures are topping 40°C. Inside, it is not much cooler, but the ornate building’s high ceilings and expansive open windows do their best to keep the heat at bay.

In the relative cool of the interior, in an L-shaped room tucked off to the side of the public galleries, a tattered three-metre-long piece of cotton sheet is spread out over a table. A sizeable patch of the cloth is missing, its borders tarnished by scorch marks. As the sheet is pulled back, gingerly, the remains of a 200-year-old painting are revealed. It depicts a scene from the ancient Cambodian poem “Reamker”, which is based on the famed Indian epic “Ramayana”. Moustachioed figures with their hair tied in buns blow conch shells while spear-carrying soldiers in cobalt-blue tunics surround a chariot. A man in an ornate headdress, wearing what looks like a tiger-print gown, points at a toddler in a box.

Originally designed to be rolled up and stored in a wooden cylinder, the work has been badly folded, leaving marks that criss-cross it like the road map of a poorly planned city. In parts, the paint has crumbled away and layers of grime caked on the image dull the colours – the ravages of heat, humidity and dirt have taken their toll on this piece of Cambodia’s art history.

Working to restore the artwork is Borany Mam, a French national of Cambodian heritage. She trained in Paris at the Ecole de Condé, then worked on Tibetan religious artworks at restoration specialists Marion Boyer before coming to the museum in 2012.

“I met the National Museum director in order to offer him my services, as I noticed some of the paintings needed urgent restoration,” says Mam. “The director was pleased and provided me with an atelier at the museum.” But it was made clear that if she wanted to carry out her project, it would have to be self-funded, spurring Mam to found the Association pour la Sauvegarde de la Peinture Khmère (Association for the Protection of Khmer Painting) in 2012. Restoring the paintings has been her passion ever since, partly paid for from the profits of a Phnom Penh restaurant that she co-owns.

If Mam’s project seems somewhat improvised, that is because it is. She is working in a field of one, being the only person in Cambodia with her expertise specialising in the conservation of preah bot, as these Cambodian religious paintings are known. Creating further difficulty, she has limited access to specialist equipment and materials.

“Everything comes from France, Thailand or Japan,” she says. “It’s possible to find some things in local markets such as pigments, solvents or tools such as brushes but their origin is uncertain and the quality is often questionable.”

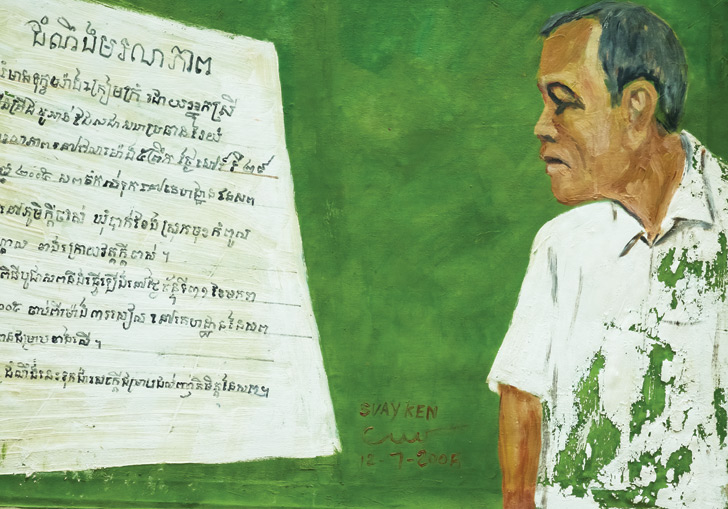

Some 850km to the southwest, in Malaysia, this is something to which fellow art conservator Rosário Marcelino can relate. High up in a well-appointed, air-conditioned apartment block on Penang’s seafront, Portuguese-born Marcelino is working to restore a collection of the late Cambodian artist Svay Ken’s paintings, ahead of an exhibition of his work at this year’s George Town Festival. Svay Ken is widely considered the grandfather of Cambodian contemporary art.

Although Marcelino’s surroundings are sleek and the artwork more modern, both experts are plagued by problems specific to the region.

“Working in Southeast Asia is very different from working in Europe because we don’t have access to the instruments that allow us to identify the materials used by the artists,” says Marcelino, who studied in Lisbon and Florence. “So unless you can interview the artist and make a record of what they are using it can be difficult.”

Through her investigations, Marcelino has found that, while in Vietnam many followed the lead of the colonial-era European tradition of using a base layer of rabbit-skin glue and chalk for their paintings, rice flour and water are more commonly used in the rest of the region.

But difficulties around determining the materials used is just the beginning. Poor storage practices and extreme environmental conditions cause mould to develop, paint to flake and dirt to build up. Not to mention the universal threat of insect damage. Burrowing termites can wreak havoc upon strainers – the wooden structures used to stretch canvas – and silverfish enjoy feasting on paper and glue.

The ravages of humid conditions can be seen in the Svay Ken collection. The artist painted on cotton, a material that absorbs and expands in the presence of water, leading to flaking paint. And the very air itself can be a menace.

“What we found in Vietnam was that there are higher sulphur dioxide levels compared to Europe,” says Adrian Jones, founder of the Witness Collection, an extensive collection of modern and contemporary Vietnamese art. “That, combined with the high humidity, effectively creates sulphuric acid in concentration in the air which attacks the paint layers.”

Marcelino works with Jones on both the Witness Collection and Svay Ken’s paintings, and it is in the Witness Collection’s gallery in Penang where she has her workshop. In November 2014, she first began to assess some of Svay Ken’s work, part of a collection of Southeast Asian art belonging to the late Bruce Blowitz. What she found was alarming.

Due to the termite threat, Blowitz wisely had the strainers removed. But an unstretched painting is an unstable painting, and cracks can appear if it is not stored correctly. Also, as the paintings were not varnished – the application of varnish being a longstanding practice in the West – dirt had adhered directly to the artworks. The grime combines chemically with the paint to alter its appearance and accelerates the degradation process of paint layers, as well as causing pigment to become more sensitive to changes in humidity.

In order to properly clean the paintings, Marcelino needed to find the correct absorbent solution to remove the dirt. She looked abroad for help, asking advice from an expert at London’s Tate Modern for guidance on the use of cutting edge microemulsions and another in the Netherlands on the use of innovative gels.

Enlisting help is occasionally necessary, says Jones, not least because the region lacks state-of-the-art X-ray machines, gas spectrometers and electron microscopes. “We’re doing what we can within the resources that we have, and where we need specialist facilities we’ve had to do that through collaboration with existing organisations that have those capabilities.”

That situation may change, though, according to Jones. In the past ten years, the art market has developed in Southeast Asia and the economic impact is significant. As the value of the region’s art has increased, collectors, museums and foundations have been paying more attention to the care of artworks.

“Whether it’s right or wrong, there’s been some correlation between the value of certain artworks and the priorities in terms of people taking care of them,” says Jones. “While in a museum that wouldn’t be the case – it’s more about the cultural value than the economic value – that’s one of the factors that has been a driving force in Southeast Asia in the conservation of artworks and that will continue as the art market develops.”

But for now, Marcelino is busy preparing Svay Ken’s paintings for exhibition. After extensive research about the artist, analysis of the paintings – in particular the exact type of zinc oxide paint he used as white pigment – and the aforementioned cleaning, the restoration process begins. Damaged and missing strainers are replaced, the canvas restretched and areas of missing paint retouched, but only when necessary.

Current good practice is to leave damage if it is considered part of the history. For example, if damage to a Vietnam War-era painting was sustained during the conflict itself, it will be left.

“If there is damage that doesn’t add anything to the painting, then I’ll try to fix it but use materials that are reversible, that can be removed a few years later if something new and better comes along,” Marcelino says.

Back in Phnom Penh, Mam makes similar calls. “This is a profession where you constantly have to question yourself – and even more so when we face a different culture and in an ancient tradition,” she says, as she tidies away the piece she is working on. “It is important to try to strike a balance between Eastern and Western restoration techniques, while keeping in mind respect for the integrity of the work.”

Southeast Asia Globe travelled to Penang courtesy of Silk Air