Not long into Casino Jack and the United States of Money, a 2010 documentary about the notorious lobbyist Jack Abramoff, who, in 2006, was sentenced to six years in prison for corruption and illegal lobbying, the eponymous rogue is filmed saying: “The buying and selling of politicians is the free market in action.”

In 2014, multinational corporations paid Washington-based lobbyists an estimated $2.6 billion to coax US politicians into proposing, accepting or rejecting legislation that impacts on the firms’ interests, according to a 2015 article in the Atlantic. In his book Dangerous Thinking, the cultural critic Henry Giroux surmised: “Policy is no longer being written by politicians accountable to the American public… [Policies] are now largely written by lobbyists who represent mega corporations.”

However unethical lobbying might appear, it has been a bedrock of US politics for almost a century. Although mostly employed by businesses, in recent decades foreign governments have realised that retaining Washington-based lobbyists can be an effective way of bending US decision-makers to their agendas in areas such as trade, internal politics, human rights and international prestige. Foreign governments spent $106m for this purpose in 2013, according to Sunlight Foundation’s Foreign Influence Explorer, a website that collates lobbying contracts.

While much of this money comes from the Middle East, Europe and East Asia, Southeast Asia Globe found that in the past ten years alone at least $14m has been spent on US-based lobbyists by Southeast Asian governments and public bodies, based on data from the Foreign Influence Explorer website. However, this figure is most likely a fraction of what is actually being spent by the region’s governments, as it is only comprised of formally disclosed lobbying contracts and fails to include payments channelled through consultancy firms or government-friendly private bodies.

One reason foreign governments lobby US politicians is to appeal for or against specific pieces of legislation. In late 2008, leaked communications revealed that Cambodia’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party paid a US-based public relations firm $500,000 to lobby against a resolution in the US Senate that, if passed, would “express the sense” that Prime Minister Hun Sen is culpable for “war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide” dating back to the Khmer Rouge era. The PR firm enlisted human rights activists to argue against the resolution – which was eventually dropped – and lobbied senior senators to reject it, the Phnom Penh Post reported at the time.

In January 2014, the Thai embassy in Washington hired the firm Holland & Knight to lobby US institutions to publicise Thailand’s efforts in fighting human trafficking and forced labour. The $400,000-plus deal proved fruitless, however, when Thailand was demoted to the lowest tier on the state department’s Trafficking in Persons report just months later.

Lobbying firms

In most of the lobbying contracts seen by Southeast Asia Globe, however, regional governments appear more interested in what is termed ‘nation branding’.

Between 2001 and 2002, Abramoff reportedly received $1.2m from the Malaysian government to bolster the nation’s image amongst US officials and to arrange a meeting between Malaysia’s then prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, and the US president at the time, George W. Bush. The meeting took place in May 2002, the Los Angeles Times reported years later, though Mahathir has denied the money came from

his government.

“From being criticised as being autocratic, anti-Semitic, a jailer of political opponents and anti-free market… all of the sudden, Mahathir’s Malaysia rose from the low ebbs of its international images to sit on the pedestal of the model Muslim nation worthy of an ally,” Karminder Singh Dhillon, a former lecturer in the University of Malaya’s Department of International Studies, wrote of the deal in the book Malaysian Foreign Policy in the Mahathir Era.

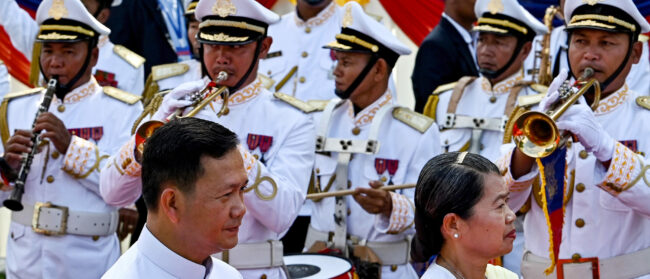

More than a decade later, in March 2015, the Myanmar government hired one of Washington’s largest lobbying firms, Podesta Group, for a one-year contract valued at $840,000 to “strengthen the ties between… Myanmar and United States institutions”, official documentation states.

Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, tweeted at the time: “Rather than really reforming, Burma will pay Washington lobbyist[s] $840k/year to pretend it is.”

Generally, governments rarely admit to lobbying. One of the only reasons these deals are made public is because the Foreign Agents Registration Act, enacted in 1938, compels US-based lobbyists who receive money from foreign governments to formally disclose the contracts, most of which are now published on the US Department of Justice’s website.

In November 2015, Michael Buehler, a senior politics lecturer at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, sparked controversy when he wrote that $80,000 had been paid to a US-based PR firm, R&R Partners, to “secure an opportunity” for Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, to address a joint session of Congress during a visit to the US. An official document filed by R&R Partners shows that the lobbying firm was paid by Pereira International, a Singapore-based political consultancy, which is described as being “retained as a consultant by the executive branch of the Indonesian government”.

When contacted for comment, a spokesperson for Pereira International said this would be “unnecessary”, as its CEO, Derwin Pereira, had already publicly stated that he “never received money from the Indonesian government” in an interview with the Straits Times.

After Buehler’s article was published on the New Mandala website, Indonesian officials roundly denounced his accusations. “They lied because my story was essentially correct,” Buehler told Southeast Asia Globe. “Parts of the Indonesian government, [which] were preparing Widodo’s visit to the US, made a big deal out of him speaking before a joint session of Congress. This is very rarely granted to foreign leaders and, therefore, carries a lot of prestige.”

However, the trip in October 2015 was far from prestigious. “Most in Washington, and the rest of America, paid little attention,” Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote in the Boston Globe. “[Widodo] held no sessions before Congress… [and only] received a smattering of coverage in the American media.”

As the article noted, Indonesia is currently ranked 66th out of 75 countries in the latest Global Country Brand Index, a report compiled by consultancy group FutureBrand, which details how well nations are regarded internationally – Cambodia was ranked 68th, Vietnam 64th, Malaysia 48th, Thailand 38th and Singapore 14th.

“Being relatively off the radar can have ramifications that go far beyond national pride. Unknownness can dramatically undercut these nations’ strategic power, hinder diplomacy, hamper their companies and make it difficult to attract global interest when they face serious crises,” Kurlantzick wrote.

In order to boost a nation’s visibility in Washington, governments do not necessarily have to appeal to politicians directly. Many of the lobbying contracts seen by Southeast Asia Globe contained implicit instructions that the lobbyists were to curry favour with the media in order to improve a country’s image.

When the Thai government retained Podesta Group in 2010 for $240,000 over three months, the prerequisite was to “help protect the [country’s] international reputation” and assist “with message development [and] outreach to media organisations and journalists”, according to official documents. Leading this task for Podesta Group was John Ward Anderson, a former foreign correspondent with the Washington Post. Between 19 May and 22 June, Anderson contacted 42 journalists from 18 outlets, met with reporters from the BBC, Time magazine and the Washington Post “regarding [their] coverage”, and organised several meetings between journalists and Thai officials, official documents show. Anderson was contacted for this article but did not respond.

Nothing about the deal was illegal, and journalists contacted by lobbyists are usually provided with press releases and statistics favourable to the lobbyist’s foreign client but not pressured to change their editorial line.

However, on occasion, objectivity is blurred. Between 2008 and 2011, US-based blogger Joshua Trevino was reportedly paid almost $400,000 to write opinion articles extolling the Malaysian government and attacking the country’s political opposition, particularly Anwar Ibrahim. Trevino also subcontracted ten bloggers and journalists to write similar articles that appeared in the Huffington Post, San Francisco Examiner and the National Review, amongst others. One subcontracted blogger, for example, wrote on a conservative news site, the New Ledger, that Anwar was a “vile anti-Semite and cowardly woman abuser”.

Trevino was not paid directly by the Malaysian government. Instead, the money was initially sourced from the lobbying firm APCO Worldwide, which was hired in 2009 for an alleged $20m by the Malaysian government to manage the country’s international image, according to online news site Free Malaysia Today. Later, Trevino’s funding came from Fact-Based Communications, a UK-based production firm, which was accused of producing propagandistic current affairs documentaries for CNN, CNBC and the BBC whilst in the pay of the Malaysian government, as well as other foreign governments, corporations and NGOs.

Lobbying disclosure

If the scribblings of journalists are thought to be able to improve a nation’s public image, then the output of think tanks arguably garners even more reverence. Since the 1970s, the number of US-based think tanks has swelled. However, as the New York Times stated in a 2014 article, at the same time their traditional source of finance – research grants from the US government – has dwindled. Because of this, most think tanks are now funded through donations from charitable foundations, corporations, individuals and, in some cases, foreign governments.

“Foreign officials describe these relationships [with think tanks] as pivotal to winning influence on the cluttered Washington stage, where hundreds of nations jockey for attention from the US government,” according to the New York Times. “The arrangements vary: some countries work directly with think tanks, drawing contracts that define the scope and direction of research. Others donate money to the think tanks and then pay teams of lobbyists and public relations consultants to push the think tanks to promote the country’s agenda.”

In 2005, the Washington Post reported on the relationship between Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia’s former prime minister, and the Heritage Foundation, a noted, Washington-based think tank. For much of the 1990s, the article stated, the Heritage Foundation vehemently criticised Mahathir’s rule. However, in August 2001, the think tank financed a trip to Malaysia for three members of the House of Representatives. It also issued briefings to Congress with a more positive slant.

a speech at the think tank CSIS in Washington in 2013

According to the Washington Post, the think tank’s “new, pro-Malaysian outlook” emerged at the same time as a Hong Kong-based consultancy firm, co-founded by Edwin Feulner, also president of the Heritage Foundation, began representing Malaysian business interests.

“[Think tanks] are generally deemed to be independent and scholarly, a perception that heightens their authority,” the American journalist Ken Silverstein wrote in his recently published ebook Pay-to-Play Think Tanks. “But the agendas, intellectual output and broader activities of think tanks, even the most highly respected ones, are conspicuously skewed by money and politics.”

The crossover between lobbyists and think tanks is demonstrated by both Feulner and the aforementioned John Podesta. As well as co-founding one of Washington’s largest lobbying firms, Podesta created his own think tank, the Centre for American Progress, in 2005.

A 2015 report on the Podesta Group website states: “At the Podesta Group, we work with think tanks on behalf of a number of clients to advance their interests.” It added a four-point plan on how to “leverage think tanks”.

In a similar vein, many think tanks also offer ‘advantages’ to their donors. The Centre for Global Development (CGD), for example, provides ‘Chairman Circle’ donors – those who spend in excess of $50,000 – the opportunity to meet privately with their experts, to collaborate in public events, and “up to three formal briefings and ideas exchange with CGD experts”. The Atlantic Council’s ‘Global Leadership Circle’, comprised of those paying more than $100,000, enjoy similar benefits as well as the “opportunity to customise your benefits package with bespoke projects in collaboration with the Atlantic Council”, according to the think tank’s website.

In June 2014, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) published a report titled A New Era in US-Vietnam Relations, authored by three of the think tank’s representatives, including Murray Hiebert, senior fellow and deputy director of its Southeast Asia programme.

According to a 2015 article published by Greg Rushford, an investigative journalist, Hiebert “confessed that the Vietnamese government paid for the study”. Donations between $50,000 and $500,000 from the Vietnamese government were listed on the CSIS’ website, Rushford wrote. However, these entries have since disappeared from the site – although it does still state that it has or continues to accept donations from the governments of Thailand, Singapore and the Philippines.

“In that study, Hiebert… criticised many Vietnamese-American pro-democracy advocates for being out of touch with realities in today’s Vietnam… When it came to Vietnam’s human rights record, Hiebert seemed to pull his punches,” Rushford wrote. The implication being that US officials in Washington, who might use this report to make policy decisions and might believe the report to be impartial, were only being told what the Vietnamese government wanted them to hear.

When asked whether these allegations were true, Hiebert failed to directly answer the question and instead told us: “All of CSIS’ reports provide our scholars’ best analysis and recommendations. They do not promote donor interests. That is certainly true in my case.”

This may be correct, but what if scholars’ apparent bipartisanship was never completely impartial in the first place? This is the allegation put forward by a number of commentators, who point not to their affinity with governments, but rather to their close links with business interests in the region.

A chapter of Silverstein’s Pay-to-Play Think Tanks is dedicated to the CSIS’ role in Southeast Asia, specifically the think tank’s senior advisor for its Southeast Asia Programme, Ernest Bower. In 2004, Bower founded BowerGroupAsia, a consultancy firm for companies looking to invest in or expand operations into Asia. It now has offices in nine Southeast Asian countries.

“Bower’s value as a door opener to his corporate clients is based on his close ties to government officials,” wrote Silverstein – adding that Bower was bestowed the honorific title of datuk by the Malaysian government, “who are no doubt pleased with his ability to influence policy and debate in Washington through CSIS”.

Hiebert and Christopher Johnson, advisor and analyst at CSIS respectively, are also directors at BowerGroupAsia – a fact not stated on their biographies on the think tank’s website.

Victor Manhit, BowerGroupAsia’s managing director in the Philippines, is also the founder of Stratbase Consultancy and president of its think tank, Stratbase Research Institute. In partnership with Philippines Inc, an alliance of some of the country’s wealthiest businesspeople, Stratbase helped launch the US-Philippines Strategic Initiative at CSIS last year.

When Manhit was asked whether there was an expectation that CSIS would take a pro-business approach to the Philippines, he replied: “Our partnership with CSIS is for their experts to examine the US-Philippines relationship as they see fit. The conclusions and recommendations they draw are their own.”

“The synergy between the BowerGroupAsia’s agenda and CSIS’ Southeast Asia programme is troubling,” Silverstein wrote, adding that one would expect the founder of a business consultancy to be “relentlessly pro-business and not to dwell much on issues like human rights. After all, more trade fattens the bottom line of corporate clients. With an allegedly independent think tank, you’d expect a somewhat more balanced approach.”

Indeed, the website of CSIS states that it “views business leaders and corporations not simply as financial supporters, but also as valuable partners in the policymaking process”.

When Southeast Asia Globe contacted Bower, the response came instead from Andrew Schwartz, CSIS’ senior vice-president for external relations. He said that Bower has “transitioned out of CSIS” – although he will remain an affiliate and chair its Southeast Asia programme’s advisory board – before failing to answer questions about the relationship between BowerGroupAsia and CSIS.

It is not only within CSIS that this revolving door between business interests and think tank associates are found. To name but a few: Walter Lohman, director of the Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Centre, was the executive director of the US-Asean Business Council. Vikram Nehru, senior associate in the Asia Programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, served at the World Bank between 1981 and 2011.

In fact, one would be hard-pressed to find a senior member of a think tank specialising in Southeast Asia who has not, at one time, held a post in a local American Chamber of Commerce, the US-Asean Business Council, the World Bank or another pro-business group.

“[Some] ‘academics’ are really just lobbyists and bagmen for US corporations in Asia,” said Buehler. “The links between World Bank staffers-turned-lobbyists-turned-academics, such as Ernest Bower… is a classic use of third-hand academic prestige to curry second-hand political favour. It is probably meant to put some social cosmetics on special interest agendas and provide an aura of ‘credibility’ and ‘academic objectivity’ to what are essentially very ideologically driven policy suggestions.”

The Land of the Lobby

In 1869, the American journalist Emily Briggs wrote thusly about a new monster invading the US capital: “Winding in and out through the long, devious basement passage, crawling through the corridors, trailing its slimy length from gallery to committee room, at last it lies stretched at full length on the floor of Congress – this dazzling reptile, this huge, scaly serpent of the lobby.”

This description of lobbying – the practice of paid advocacy in which interest groups seek favour with lawmakers, typically members of Congress in the US – reveals its monumental growth after the American Civil War. Although lobbying had been common since the first days of the Republic, it became pervasive in the 20th century, furrowing itself into all branches of the US political structure.

The notion of an unscrupulous monster in the halls of Washington continues today as lobbying has become a multibillion-dollar industry. It has evolved in recent decades with the formation of political action committees (PACs), formed by interest groups that funnel money into the campaigns of those seeking political office. Cutting out the lobbyist middleman, there is an inherent expectation that, once elected, the enriched candidate will toe whatever line the PAC wishes.

While many onlookers might consider lobbying disreputable at best – subverting democracy, at worst – fewer than a handful of individuals have ever been convicted of irregularities, and there is little doubt that the practice will continue to survive for years to come.