Joko Widodo’s rise to the Indonesian presidency was meteoric, but many would argue that he has stalled since landing the top job. One year into his term, the negatives are outweighing the positives

A little over a year ago, Joko Widodo and Jusuf Kalla were paraded in a horse-drawn carriage along Jakarta’s main thoroughfares, Jalan Sudirman and Jalan Thamrin. A sea of jubilant supporters lined the streets, cheering the royal-style procession, as the men who had just taken their oaths of office as Indonesia’s next president and vice-president made their way to Merdeka Palace. There, Indonesia’s sixth president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, was waiting to welcome his successor to the country’s seat of power.

It was the first peaceful transfer of the presidency that the country had experienced, passed from a former general whose presidency was seen as a remnant of the country’s military-controlled past to a president many perceived as a fresh start – someone from outside the political and military establishment.

The pair’s supporters were soaked in euphoria, and those who were in the capital celebrated the event with a rock concert that lasted through the night. Hopes were high that, from this day forward, the man they voted into power in a tightly contested election would lead them to a better Indonesia through his commitments to root out corruption, invest in much-needed infrastructure, boost economic growth, improve the welfare of the people and become the world’s maritime axis. Widodo was widely lauded as a man of the people; a checked shirt-wearing, small-town boy from Java; an average Joko.

But almost a year after that star-studded concert, political pollster Indo Barometer found that enthusiasm has dampened, with 54% of respondents saying they are not satisfied with Widodo’s performance.

Muhammad Qodari, executive director at Indo Barometer, said that the president’s public approval rating had slumped to 46% in September from 57.5% six months earlier. Meanwhile, Kalla’s approval rating had dropped from 53.3% to 42.1% during the same period.

“Five out of six of the most important issues in Indonesia are related to the economy. The majority of the public – 65.6% – said that people’s welfare is bad,” he added. Indeed, the president’s popularity has dwindled almost in tandem with the economy, as growth dropped below 5% in the first quarter this year, a more than five-year low.

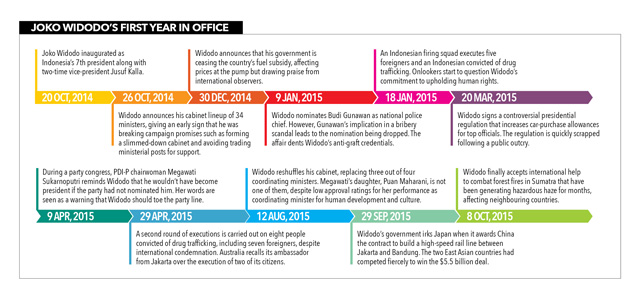

Widodo, also known by the portmanteau Jokowi, had made his first controversial decision within just a few months of taking office. Announced on December 30, his policy of scrapping the country’s fuel subsidy that kept prices at the pumps low but cost the government $19.6 billon, or 15% of the state budget, last year was met with wildly differing opinions.

IMF managing director Christine Lagarde praised the decision during her visit to Indonesia, while the Economist stated that it would make the country’s “fiscal prospects brighten”. Despite such international praise, local economist Ichsanuddin Noorsy, of Airlangga University in Surabaya, says that it was disastrous in a country where about half of the 250 million population lives below the UN poverty line of $2 per day.

“Joko took the wrong advice by cutting the fuel subsidy. It was a massive blow to the people’s purchasing power, especially those in the middle to lower bracket, and it has not been well compensated through his welfare programmes such as the Indonesian Health Card,” said Ichsanuddin.

In what is widely seen as one of Widodo’s most memorable speeches as president, the opening address at April’s Asian-African summit, he said that relying on the IMF, World Bank and the Asian Development Bank to fix the economy is an “obsolete” view.

“It was a misguided statement,” said Ichsanuddin. “How could he say that when he took the move, endorsed by global lenders, to cut the fuel subsidy?”

Perhaps even more damning, however, is a growing public perception that Widodo’s administration is in disarray. Repeated policy flip-flops and public bickering between cabinet ministers do not give the impression of a capable, united government.

Widodo also took the decision to dissolve the Presidential Working Unit for Supervision and Management of Development. Set up by Yudhoyono, the unit was tasked with measuring, monitoring and evaluating the government’s progress; it also provided the president with real-time feedback on particularly pressing issues across the country.

Perhaps the biggest public mistake came from Jokowi himself in April, when he admitted he had not fully read a draft regulation before signing off on it. Again, a quick policy reversal was announced to the regulation that had authorised a substantial increase in car-purchase allowances for top officials. Widodo pointed out that the job of screening draft regulations should be carried out by ministers before they reach the presidential pen, but it did little to curtail accusations that Widodo lacked the attention to detail necessary for a president and that he displays poor judgement in policy making.

“There is an incoordination between government officials that is evident in the public sphere,” said Imelda Sari, a spokesperson for the Democratic Party, adding that Jokowi and his government should stop blaming external factors for the lack of progress in achieving goals such as increased economic growth.

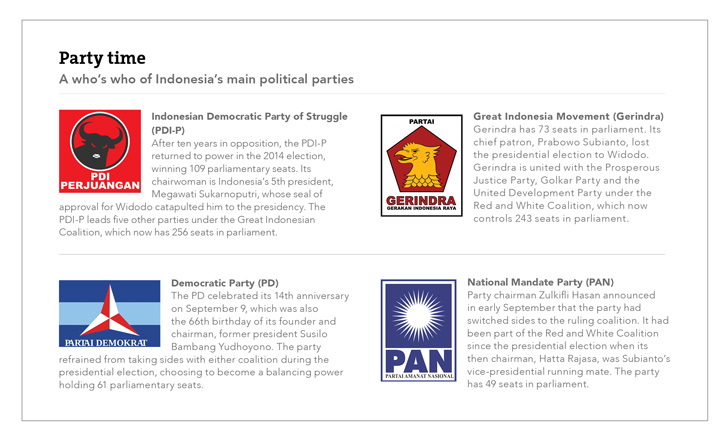

There are certainly other internal factors at play. The Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) is the country’s largest political party, founded by Megawati Sukarnoputri, the political heavyweight daughter of the country’s revered founding father, Sukarno, and a former president herself who remains chairwoman of the party.

With Widodo having run for the presidency on a PDI-P ticket, onlookers speculate that Megawati has been pulling the strings throughout the election and into the presidency. This and other bureaucratic concerns have hampered Widodo’s ability to stick to many of his election promises, in particular the stifling of both nepotism and the horse-trading of government positions. His stated aim was for a cabinet comprised of professionals.

“It was quite convincing for the public,” said Siti Zuhro, a political expert from the Indonesian Institute of Sciences.

Tom Power, an Indonesian political researcher at the Australian National University, pointed out that the distribution of positions is inevitable in multiparty democracies, but that the image Widodo projected during the presidential campaign fostered a sense among the public that he would be different.

“I think the reverse is actually true, because he doesn’t have a position of strength in the political party,” Power said. “He is forced to seek compromise with a whole host of vested interests to make himself feel as though he is secure in his position. He doesn’t have the political apparatus to support him so he has to, sort of, buy support using his position.”

The lineup of Jokowi’s cabinet revealed much about his ability to stamp out patronage and nepotism. There was Rini Soemarno, a Jakarta corporate figure linked to numerous corrupt deals, who was named minister for public enterprises; new defence minister Ryamizard Ryacudu, a former army general with links to Megawati’s father, as well as a questionable human rights record; and Puan Maharani, Megawati’s own daughter, who was appointed coordinating minister for human development and culture despite having no known expertise in such matters.

Although he largely failed to fill his cabinet with the professionals promised, Widodo was able to make some positive appointments, such as the university rector Anies Baswedan as minister for school-level education, and the former railway chief, Ignasius Jonan, as transport minister.

Indeed, according to Indo Barometer’s survey, both of these ministers rank highly in terms of public satisfaction. Baswedan has the second-highest rating of any minister with 54.2%, while Jonan ranks seventh with 34.5%.

In the same survey, Widodo’s most popular policy was his Indonesian Health Card Programme, which was launched alongside the Indonesia Smart Card last year. These health and education programmes reach tens of millions, offering many benefits including free health insurance for the poor and guaranteeing 12 years of free education, along with free higher education for poor students who pass university entrance exams.

“The concept of the Health Card policy is correct,” said Hasbullah Thabrany, a public health policy expert from the University of Indonesia. “But it requires further improvements in terms of broader target recipients that should include all senior citizens, better data management of its recipients and that patients should have the right to choose their preferred doctors.”

Perhaps surprisingly given the global uproar, Widodo’s decision to follow through on the executions of convicted drug traffickers in April also met with public approval. A staggering 84.9% of respondents in the Indo Barometer survey said they believe drug traffickers should be executed, while 64.5% of them believe that Widodo is being firm on this policy.

One such advocate is Abdul Mu’ti, the secretary of Muhamammadiyah, Indonesia’s second-largest Islamic organisation. “If we don’t take firm action now, it would create negative multiplier effects. In fact, those effects already happened,” he said. “Our law still rules that the death sentence is applicable in Indonesia, but the executions should be carried out to provide justice for all, not just to seek popularity.”

For some, despite his undoubted failings, Widodo remains a beacon in the murky world of Indonesian politics. And the impression sometimes persists that it is the political system that is at fault, rather than Jokowi himself, and that he is often hamstrung by the ministers that he may or may not have had thrust upon him. His perceived honesty and everyman appeal still holds for Maman Imanulhaq, a National Awakening Party politician, though he sees stifling bureaucracy as a stumbling block that Widodo must reform quickly if he is to execute his pro-people policies.

“Jokowi is still on the right track,” said Maman, whose party is part of the ruling Great Indonesia Coalition. “He is a leader who is modest and doesn’t implicate himself in nepotism. He doesn’t set an example of a hedonistic style as many officials here do.”

Keep reading:

“Can Southeast Asia stop dumping plastic waste in our oceans?” – New research shows that plastic waste in our oceans is far worse than previously thought, and Southeast Asian nations are among the worst offenders