It was the end of history, they were told, but the days kept dragging on. Across the globe, the exhausted republics of the communist world shook beneath their own weight, struggling to keep up with the ruthless expansion of the free market across their borders. Walls came down, and armies drew back: democracy, the headlines screamed, had arrived.

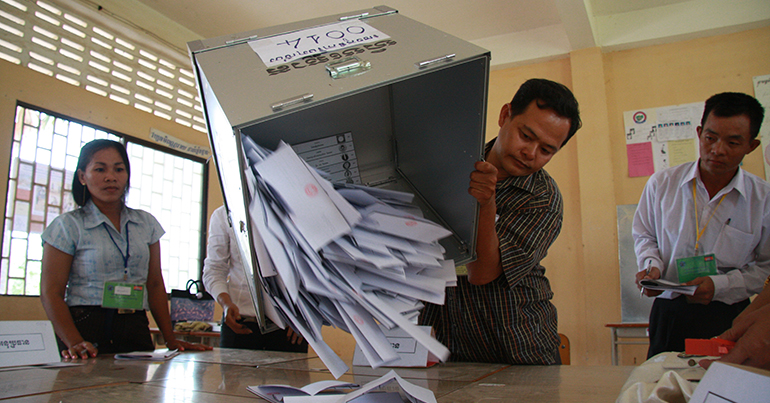

Twenty-five years ago this September, the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (Untac), seeing that all things were accomplished, folded itself one last time into its crisp, white fleet of Land Rovers and headed west into the setting sun. Under the auspices of an international community triumphantly forging a new world order following the collapse of the Soviet Union, a nation torn apart by decades of famine, war and foreign occupation was once again in command of its own destiny. A constitution had been drafted, and elections held: nine out of ten eligible Cambodians cast their ballot. One party won. Another, led by former Khmer Rouge defector Hun Sen – now prime minister – ruled. Threatening once more to plunge the country into the chaos of a secession crisis, he stared down the aid workers and administrators. Their dreams of democracy wilted. They blinked.

A quarter of a century on, with the main opposition party dissolved and its leadership broken and scattered, Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has put aside the pretence of a popular mandate in favour of effective one-party rule, disenfranchising more than three million Cambodians who voted for the opposition and ensuring the CPP will face this year’s national elections virtually unopposed. For those Cambodians who have witnessed firsthand the growing popular demand for political change, the nation’s descent back into authoritarian rule has been a bitter blow.

But for Sebastian Strangio, author of Hun Sen’s Cambodia, the international community’s efforts to impose Western-style liberal democracy on the Southeast Asian nation had been flawed from the beginning.

“The real purpose of the Paris Peace Agreements, which wasn’t actually written in the text, was to end the Cold War in Cambodia and to detach superpowers from Cambodia’s internal affairs, and get them out of Cambodia,” he said. “At the same time, Paris also had this mandate of creating a sustainable liberal democracy and full respect for human rights – an aim that flew in the face of everything that we know about how democracies emerge or have emerged through history. It was vastly overambitious – and I think that most governments recognise that.”

China doesn’t ask Hun Sen any questions, they approve his policies, they keep writing blank cheques and they’re a firm, party-run country

David Chandler, Historian

Strangio described a decades-long dance between the predominantly Western nations who donated millions in aid and support to the war-ravaged nation and an embittered strongman who, despite refusing to be bound by the ballot box, grudgingly maintained the façade of a nation taking its first shaky steps towards democracy.

“The donor countries are sort of trapped within the terms of reference that they’ve set for themselves – they have to pretend that it’s possible for Cambodia to democratise,” he said. “And Hun Sen has sort of done donor countries a favour by holding elections that can reasonably be claimed to be reasonably free and fair – and so the difficulty that these governments are facing now is that Hun Sen has essentially revealed the whole thing to be the sham it always was. He’s harmonised appearance with reality, and now they’re stuck – and forced to actually put political resources on the line in order to back up their words about their desire for Cambodia’s democratisation.”

Perhaps the most decisive factor behind the government’s crackdown on domestic dissent has been its increasing reliance on China’s rising star for political and economic support. Credited with economic reforms that have lifted more than 500 million people out of extreme poverty – though at cost of a growing divide between rich and poor – the fledgling superpower emerged from the final days of the Cold War as an economic powerhouse ready to do business with the victorious West. Now, though, with the US seemingly consumed by political schizophrenia, China seeks to challenge the ailing superpower’s long-held global supremacy.

International Public Policy research fellow Alvin Cheng-Hin Lim told Southeast Asia Globe that Cambodia’s increasingly cosy relationship with China – which outspent the US on bilateral aid to Cambodia by a factor of four to one last year and by ten to one in investment capital – had created a buffer between the righteous indignation of the West and a nation sick of being lectured on how to conduct its affairs.

“In this current crisis, we are likely to see a repetition of the old pattern: the pain of the retrenchment of funding from the West will be ameliorated with increased aid, investment and debt forgiveness from China,” he said. “This will especially remain the case so long as the Cambodian government continues to support China on pressing issues like the South China Sea in regional multilateral forums like Asean.”

David Chandler, historian and author of The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War and Revolution since 1945, described Hun Sen’s decision to pursue China’s political and economic backing as a move born out of the strongman’s characteristic pragmatism.

“This is the sweetest arrangement he can make – they don’t ask him any questions, they approve his policies, they keep writing blank cheques and they’re a firm, party-run country, and he understands that,” he said. “They’re interested in economic development, and so is he – they have some history of a communist past, they’re fraternal, as they are with Vietnam – I don’t see him looking anywhere else.”

It is a pattern of patronage that has deep roots in Cambodia’s political history. Over the centuries, as the encroaching Thai and Vietnamese kingdoms ate away at an empire that once spanned all of Indochina, Cambodia’s sovereigns sought protection from its more powerful neighbours, ceding the nation’s wealth and territory in return for its continued survival. Now, as during its days of French colonial rule, Strangio argued, Cambodia’s leaders crave a powerful ally for the nation – though one, he stressed, that didn’t ask them to surrender anything they weren’t willing to give.

“I think they’d be perfectly happy to have the United States play that role, except that the US has this pesky, meddlesome obsession with the idea that Cambodia can become a democracy,” he said. “And I think that’s something that the Cambodian leadership doesn’t understand and greatly resents and sees as hypocritical cover for regime change, essentially. And there’s definitely a kernel of truth to that assertion.”

Certainly, Cambodia seems to bear the brunt of US condemnation of human rights abuses in the region – more so, even, than the military junta in Thailand or Vietnam and Laos’ repressive one-party regimes. Perhaps that is not surprising given this is the nation that the international community once poured more than $1.5 billion into to drag it into democracy – to say nothing of the billions spent on aid and development since. More pragmatically, though, Thai and Vietnamese exports to the US in 2016 reached $28.6 billion and $38.1 billion respectively in 2016, according to figures from the OECD. By contrast, Cambodia’s exports to the US barely passed $2 billion. For many, this selective blindness is little more than an exercise in cynical realpolitik – and one not lost on a prime minister who once watched the US, still bitter from its defeat in Indochina, close ranks behind the Khmer Rouge after the murderous regime was driven from power by the Vietnamese-backed invasion.

For a government that is irritated by the idea that its sovereignty takes a backseat to the seemingly arbitrary enforcement of an international law not of its making, though, Cambodia’s rush to indebt itself to China’s sweeping economic vision may prove short-sighted. Paul Chambers, a lecturer at the College of Asean Community Studies at Thailand’s Naresuan University, said that China’s stagnant economic growth and ambitious One Belt, One Road (OBOR) development strategy for the region left the smaller nation vulnerable to the changing fortunes of its new patron.

“Cambodia is part of the maritime road of the One Belt, One Road – but ultimately the OBOR could cost up to $8 trillion,” he said. “And if China’s economy fails to make this strategy succeed, the OBOR could drain the economy of China. We’ll see if China can fulfil its dream, but Cambodia’s become a part – I hate to use the term neo-colonial, but Cambodia’s become sort of a part and parcel of China’s expansion.”

Cambodian political blogger Noan Sereiboth agreed that the Cambodian government was in danger of becoming too dependent on China to maintain its grip on power.

“Politically and economically, Cambodia cannot be solely reliant on China for economic growth in terms of development and its democratic process in the country,” he said. “The CPP can show its pretended and committed real reforms to satisfy voters. Building more infrastructure, a crackdown on crime, a market for their products and jobs are what the grassroots need for their living.”

With a staggering 2% of its 7% GDP growth in 2015 dependent on garment exports, which predominantly go to the US and European Union, though, Cambodia’s economy remains bound to Western consumers – a fact that has motivated a growing number of activists to call for debilitating sanctions against the Cambodian government following the CNRP’s dissolution. Chambers said that while an embargo against garment exports would devastate the Cambodian economy, such measures would only feed in to Hun Sen’s increasingly strident rhetoric against Western intervention.

“If you look into his life as prime minister, he’s always used anti-Western, nationalistic propaganda,” he said. “I don’t think that Western targeted sanctions are going to be very effective against him. You could always use a carrot and a stick against Hun Sen [in the past], but now he has China at his back.”

With little sign of public protests since security forces gunned down four garment workers during a demonstration in 2014 following allegations of foul play in the 2013 national elections, the belief that the dissolution of the CNRP could mobilise the “colour revolution” so feared by the government is looking faint indeed. Nevertheless, Sereiboth argued that without pursuing popular reforms, the government’s grip on power would not be beyond challenge.

“The popularity of the CPP is already dramatically down if we looked at the [national] election results in 2013 and [local election results in] 2017,” he said. “The CPP is not in a strong position of support for its leadership of the country – people have had enough of this regime for promising reforms which have not yet been accomplished. The CPP knew it would be hard for them to compete with the main opposition party if it still existed to compete next year.”

Chambers argued that Hun Sen’s political survival now depended largely on his ability to protect the business investments of his new, wealthy Chinese patrons, even drawing a parallel with the abrupt political overthrow last year of long-serving Zimbabwean leader Robert Mugabe.

“Mugabe had created a state that was being bankrolled in many ways by China, but some have said that the coup leaders had flown to Beijing earlier and that the Chinese wanted to protect their investments – and so they were OK with letting Mugabe go, being overthrown, and replaced with some other individual who would continue to protect their interests,” he said. “So in this regard the Chinese might decide to be willing to expend Hun Sen if he seems to be failing or unable to sustain their investments.”

Astrid Norén-Nilsson, author of Cambodia’s Second Kingdom: Nation, Imagination and Democracy, was sceptical that China would so overtly support a change of leadership in Cambodia.

“It is difficult imagining circumstances ever coming to Beijing withdrawing its support,” she said. “It is entirely possible, however, that image-conscious Beijing will urge Phnom Penh to tone down perceived excesses of a visible kind.

“Hun Sen is a Buddhist – he knows that everything passes, including himself, and that all power is ultimately ephemeral.

Sebastian Strangio, author, Hun Sen’s Cambodia

“Now that the political party opposition has been vanquished, the government will concentrate on detecting, counteracting and pre-empting challengers among the grassroots. This means a larger, more diffuse battlefield, where broader segments of people may find themselves in the crossfire.”

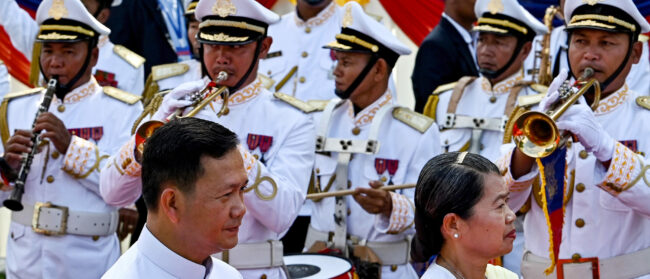

More worrying to Beijing than the excesses of its vassal, though, could be the long-running rumours of Hun Sen’s declining health. After several abrupt visits for medical treatment in Singapore last year, a visibly frail Hun Sen presided over an immense Buddhist prayer ceremony at Angkor Wat, the seat of the mighty Khmer Empire, in December. Despite the majesty of the setting, though, the premier moved haltingly, looking frailer than his 65 years.

“The question of succession is becoming more pressing with every passing year,” Strangio said. “Hun Sen is a Buddhist – he knows that everything passes, including himself, and that all power is ultimately ephemeral. The last thing he wants to be doing is fighting off a powerful opposition while also trying to engineer this transition within his own party. The current crackdown is geared towards creating for Hun Sen this space to begin to solve this problem – and to ensure that the CPP has a solid succession plan that keeps everyone’s power and interests intact and maintains the balance between the elites and leadership that makes up the Cambodian ruling class.”

Despite the prime minister’s clear attempts to build the public profiles of his sons – who have all been appointed to plush positions within the armed forces, state security services and National Assembly – there is the rumoured threat of a challenge from interior minister Sar Kheng, an old-guard factional leader who wields supreme power over the police and security forces. Regarded by some in the international human rights community as more moderate than the hardline Hun Sen, the role that the ageing Kheng will play in the inevitable succession remains the source of much speculation.

“The question of succession will depend in large part on who will eventually take over the Hun Sen family’s vast patronage network”

Alvin Cheng-Hin Lim

“I have heard lots of stories from Cambodians about the health of Hun Sen,” Chambers said. “And China is probably also worried, because they want to sustain their investments. Tea Banh, the defence minister, is weak – he wouldn’t be competing with Sar Kheng. So I think Sar Kheng is ultimately, at this point, the person who would consolidate control, either with one of the children of Hun Sen or against them. And I think if he did it with them it would be better, but of course [eldest son] Hun Manet would be some sort of a front man for Sar Kheng.”

For a nation where power is determined less by official titles than it is by personal networks of patronage, the vast network of business connections strung together by Hun Sen over his decades of power make any future transition a matter of tense negotiation. A 2016 report released by London-based corruption watchdog Global Witness described a “huge network of secret deal-making, corruption and cronyism, which is helping to secure the prime minister’s political fortress”, revealing that the prime minister’s family had interests in at least 114 local companies with a combined share capital of more than $200m – a likely fraction of the family’s immense hidden wealth. According to Lim, it was this invisible web of influence that would determine the future leadership of the nation.

“The question of succession will depend in large part on who will eventually take over the Hun Sen family’s vast patronage network,” he said.

Now, though, as a new year dawns in the Kingdom, the dream of a Cambodia governed by the mandate of its people rather than power of its patrons is already fading in the harsh light of day. Instead, it remains on a precipice between the righteous indignation of the Western powers that have helped shape modern Cambodia and the domination of an ascendant China. For Chambers, it is a balancing act that will allow no missteps.

“It kind of reminds me of Norodom Sihanouk back in the 1960s, when Sihanouk was trying to play off the North Vietnamese, the Chinese and the United States – and it didn’t work out,” he said. “So there could end up being a real perfect storm for Hun Sen and for Cambodia, especially with Trump, [where] Cambodia ends up in the heart of a new Cold War. Which I don’t think is good for anybody.”