Rice farmers across Cambodia and Myanmar have been left scrambling for new markets for their crop after the European Union announced on Wednesday that it will now be imposing hefty tariffs on long-grain Indica rice from both Southeast Asian nations for the next three years beginning today.

The decision, announced by the European Commission this week, follows a month-long investigation that confirmed the increase in Indica imports from Cambodia and Myanmar has been damaging to EU rice producers.

In December, the Commission held a vote on this issue among its 28 EU state members, but did not receive a majority in favour of imposing the tariff measures. In the absence of strong opposition to the proposal, the Commission made the final decision itself on 16 January.

Representatives of European farming groups told Reuters that they are grateful for the Commission’s decision, as the cheap rice imported from Southeast Asia has been contributing to farmers’ abandonment of crops and exodus from rural areas.

Farming group Copa-Cogeca said rice imports from the two Asian countries increased from 9,000 tonnes in 2012 to 360,000 tonnes in 2017, leading to a collapse in prices across the European continent. In 2018, approximately 30% of all EU rice imports originated from countries with duty-free status – with the bulk being shipped in from Cambodia and Myanmar.

“This surge in low-price imports has caused serious difficulties for EU rice producers to the extent that their market share in the EU dropped substantially from 61% to 29%,” the Commission said in a recent statement.

Rice is currently grown across eight southern European countries including Italy, whose government initially requested the launch of the Commission’s investigation in March 2018 in the name of “protecting the Italian and European rice industry”.

Cambodia and Myanmar have enjoyed duty-free rice export to Europe since 2010, when the EU dropped its tariffs on the crop as a benefit of the Everything but Arms agreement, a policy which aims to promote European trade of goods with the world’s 50 least-developed countries. Other more developed countries in Southeast Asia, including Thailand and Vietnam, have long been paying tariffs of around $200 per tonne for white rice exports to the EU.

Impact on Cambodia’s and Myanmar’s Economies

For countries that have long benefitted from free access to the European market, the new tariffs are a steep price to pay: for the first year, the two countries’ Indica rice exports will be charged a duty of approximately $200 per tonne of rice, with the duties gradually dropping to $171 and $142.50 per tonne, respectively, over the course of the following two years.

For both Cambodia and Myanmar, rice is a major export – and Europe has become their most profitable market.

The EU is currently Cambodia’s largest destination for exports, with nearly 43% of all exported rice – or approximately 270,000 tonnes’ worth – going straight to European markets. But while Cambodia’s exports to the EU have been on the rise in recent years, the country’s overall rice exports suffered slightly last year: the industry took a 1.5% dip in 2018 compared to 2017, with officials citing high production costs, international competition and a potential EU tariff as the cause.

Just under a week before the Commission’s Wednesday announcement of its decision, Cambodia Rice Federation vice-president Vong Bun Heng told a local news outlet that the very threat of an EU tariff on Cambodia’s rice has already proven damaging to overall exports.

“Some international buyers hesitate to place orders when they hear about implementation of the EU safeguard,” he said. “There is a need for our rice, but the choice of buyers is limited.”

Chan Sophal, director of the Centre for Policy Studies, a research unit of the Cambodian Economic Association, told the Phnom Penh Post that the Kingdom could see its rice industry in critical condition in the face of the EU tariffs. In order to offset the additional duty costs, he said, local rice farmers will have to focus on cutting production costs, and may need to switch up their crops altogether.

“The government should consider reducing the electricity cost and port fee to help our rice industry to remain or be more competitive,” he said. “I think [the impact of the tariff] will depend on the substitutability of the Cambodian rice in EU market outlets. If they like Cambodian rice, the supermarkets and consumers in Europe may not mind paying a bit more.”

According to AMRU Rice Cambodia chairman and CEO Song Saran, Cambodian rice exporters should focus on expanding to new markets – but for now, it needs Europe.

“We need the EU market and we cannot afford to lose it. So we will have to find a way to lower our operating costs to improve competitiveness,” he said.

Myanmar is in much the same boat, as Europe has steadily grown to become one of the country’s major markets. Myanmar exported upwards of $320 million worth of rice in 2017, the same year it reached an all-time high of 293,000 tonnes of rice exported to Europe.

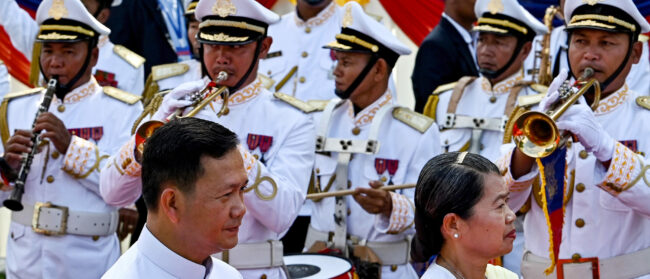

At a World Economic Forum in September, Myanmar state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi noted that Myanmar’s rice exports have been on the rise for years, achieving “pre-war” levels in 2017 thanks to access to foreign markets.

“[Our rice export success] has not affected the rice exports of [neighbouring countries like] Vietnam or Thailand,” she said. “The fact that we have been gaining our position in the world rice market does not mean that other local markets have suffered.”

But this could change now that the European market has set a high barrier for entry to the Indica rice market, forcing farmers to look closer to home as they seek out different buyers.

Last week, general secretary of the Myanmar Rice Federation Ye Min Aung spoke about the potential negative effects of the EU’s decision to impose duties on the country’s rice exports.

“We have seen increased income as we are able to export quality rice to EU market,” he told a local news outlet. “Unless we have [duty free export] rights, we have to compete more with other countries. But to do so, we have much difficulty – we don’t have enough ports and warehouses.”

However, others are for more optimistic about the potential effects of the new tariff, which some Burmese industry insiders – including Myanmar Rice Federation joint secretary Lu Maw Myint Maung alongside several local rice exporters – claim will only affect about 60,000 to 100,000 tonnes of Indica exports. Even if only 100,000 tonnes of Myanmar’s exports were to be affected, however, the new tariff would still result in a loss of approximately $20 million for the country, should Myanmar choose to send its rice to the EU in the upcoming year.

According to Hla Maung Shwe, deputy chairman of the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry, it could be worse – the EU could have chosen to target duty-free garment imports, which are the backbone of several developing Southeast Asian economies.

“This decision will not affect us very much on rice exports to Europe, but if it were on our garment exports, it would hurt,” Hla Maung She told Radio Free Asia.

In Cambodia, officials are looking at the new tariff as an opportunity, and a sign from the EU that the Kingdom no longer needs preferential treatment. Cambodia’s Council of Ministers spokesman Phay Siphan told RFA that the government is unconcerned by the tariff, though he admitted it would have an impact.

“Imposing a tax on Cambodia is a positive development, which proves that Cambodia is able to pay duties like other countries,” he said. “We know that imposing the tax will affect us, but we must be ready to compete on a level playing field with other countries in trade.”