The Jinsha casino was air-conditioned and thick with cigarette smoke, a combination that had the slightly disorienting effect of making it feel both clean and dirty at the same time. In a low-ceilinged room Chinese gamblers sat around felt-covered tables, throwing down stacks of 100-yuan notes on a card game known as longhu – ‘dragon-tiger’. Next to each punter were stuffed ashtrays, cans of Red Bull and Chairman Mao staring – it could only be disapprovingly – from piles of Chinese banknotes.

In a small side room, a solitary man sat hunched over a solitary table. With one hand he rattled a stack of 10,000-yuan ($1,600) casino chips; the other moved 40,000-yuan worth of chips into position before tapping impatiently on the felt. “Show! Show!” he barked. The young female croupier swept up a few cards and placed them on the baize. The man paused a moment; he rubbed the cards in superstitious circles, trying to conjure a lucky hand. Then he bent the corners upwards to view his hand. Mangling the unlucky cards in his fist, he hurled them back at the croupier in frustration. “I don’t like to gamble like this,” said Jiang Guanfu, a 38-year-old Yunnanese businessman who acted as my casino guide. “I always lose!”

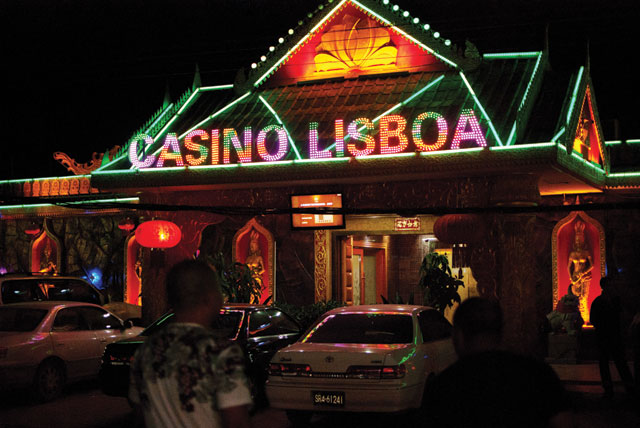

Welcome to Mong La, the largest town of ‘Special Region No. 4’, a sliver of autonomous territory in Myanmar’s eastern Shan State. For more than two decades, the armed militia that runs this jungle fiefdom of 89,000 has survived by packaging the area as a haven of illicit pleasures for Chinese tourists – a neon-fretted settlement of hotels, brothels and restaurants. The core appeal of Mong La, however, is its casinos, which pull in thousands of tourists each month from China, where gambling is illegal outside of Macau.

No alcohol is served inside the casinos of Mong La – only Chinese tea, soft drinks and uppers such as Red Bull. Special rooms with reclining chairs and dim lighting are set aside for serious gamblers to take a rest. In 2003, angry that corrupt officials were losing millions of yuan in Mong La’s casinos, Chinese authorities intervened and shut the operations down. (The shells of abandoned casinos and nightclubs can still be seen in the hills around town, their glitzy facades fading in the tropical heat.)

In response, the authorities in Mong La simply created a new casino zone 16 kilometres to the south, at the village of Wang Hsieo. Here, behind blazing neon and Romanesque columns, the gambling goes on around the clock. To evade official bans in China, many gamblers simply cross into Mong La illegally. “It’s very easy,” said Wang Bangyuan, a public health specialist who has travelled extensively in the Myanmar-China border region. “People simply walk across the border, without any documents.”

The tourism-and-gambling boom in Mong La has drawn in many more Chinese who have set up restaurants, grocery stores and other businesses. In the centre of town I met Jasmine, a woman from Yunnan who has run a mobile phone shop for two years. “There was just a little money in China. It’s better in Mong La,” she said in English. “But I don’t like it here. There’s nothing much to do – there’s no good malls.”

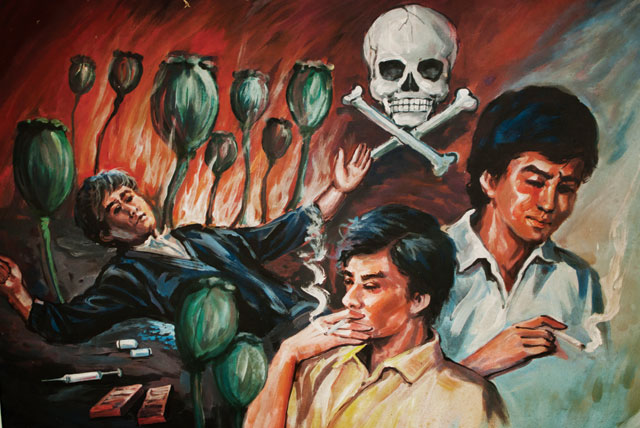

The porous border and influx of moneyed gamblers has also led to a boom in prostitution – Chinese sex workers openly ply their trade around town – and a flourishing market in endangered wildlife. At the open-air market, vendors sell bear bile powder and live monitor lizards, Tibetan antelope skulls and freshly killed muntjacs. Outside restaurants on the main dining strip are cages holding live pangolins, monitor lizards and endangered soft-shell turtles, to be cooked to order. For the more rarefied palate there is tiger bone wine – illegal in China since 1993 – drawn from tanks in which whole tiger skeletons sit pickling in a bath of rice wine and ginseng.

Nearby wildlife boutiques openly sell ivory and the skins of tigers and leopards – artefacts that come from as far away as India and Africa. At the market, one Chinese trader offered to sell me the skin of a pangolin, an endangered scaly anteater, for 200 yuan ($32). “Here, feel how soft it is,” she said, running her hands over the grey scales.

Vincent Nijman, a zoologist and anthropologist at Oxford Brookes University in the UK, said that lax law enforcement and the demand of border-hopping Chinese has created the perfect conditions for the trade in endangered animals, many of them protected by international treaties. “In terms of number and volume of the variety of species on offer, Mong La is one of Southeast Asia’s largest open wildlife markets,” he said. During a fieldtrip in January, Nijman and a colleague counted 3,300 pieces of ivory and 50 raw elephant tusks for sale around town. “It is almost like a legal vacuum,” Nijman said.

Even though Special Region No. 4 has its own security forces, they appear to take a rather hands-off approach to law enforcement. Mong La and its rugged surrounds have enjoyed “special” autonomous status since 1989, when the Communist Party of Burma collapsed after decades of insurgency. The Mong La area subsequently fell under the control of the National Democratic Alliance Army, or NDAA, led by the former Maoist Red Guard Sai Leun. Leun then cut a ceasefire deal with Myanmar’s military government, giving him autonomy in exchange for ending the insurgency. Since then, Leun has ruled Mong La with little interference from the outside, protected by an army of 4,500 men that US officials have likened to a “James Bondian private police force”.

One senior NDAA official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that in addition to casinos, the region makes most of its revenue from mining and agriculture – particularly, Chinese plantations of banana, rubber and corn. “Go around and see,” he said, “it’s all green, all rubber plantations up to the Mekong River.”

But analysts say that unlike many of Myanmar’s armed rebel groups, which have been fighting for autonomy from nearly the moment the country gained its independence in 1948, the NDAA has no political or ethnic agenda. “They don’t really want any political gains,” said Paul Keenan, a researcher at the Burma Centre for Ethnic Studies in Chiang Mai. “At this moment in time, it’s about business – and survival.”

The NDAA also has a powerful ally in the United Wa State Army (UWSA), Myanmar’s largest ethnic armed group, whose territory borders the Mong La region to the north. The UWSA has 20,000 men under arms and has long been considered one of the largest drug-producing syndicates in Myanmar. It has also been historically hostile to interference from the central government. Since 2009, when the Myanmar military dispatched troops to occupy Kokang, the ‘Special Region No. 1’ in northern Shan State, the UWSA has stationed more than 1,000 soldiers in the Mong La area, as a hedge against any future armed challenge. Tom Kramer, a Yangon-based researcher at the Transnational Institute, said the Wa are also interested in Mong La’s strategic location, which includes control over a stretch of the Mekong River and key smuggling routes into northern Laos.

Despite the economic free-for-all taking place in Mong La, Myanmar authorities have shown little inclination to alter the status quo in the border area. “I think they’ll just tolerate these groups and whatever they do – whether it’s [the] drug trade, the illegal wildlife trade – as long as they don’t do opposition politics,” Kramer said. And Wang, the health worker, said that despite continuing Chinese concerns about the region’s casinos, authorities in Yunnan are dragging their feet: “There’s still quite a lot of pressure on the Mong La authorities to close down all the casinos. But in terms of enforcement, it’s not very serious at the county level.”

Back in town, I met Abraham Than, a retired bishop living next to the Catholic church perched on a hill overlooking town. When the 88-year-old Than moved to Mong La in 1969, from Taungoo in central Myanmar, there was no neon and no hotels – nothing but jungle and a smattering of Shan and Akha villages. “There were no houses, no buildings, nothing. During these past four, five years it has become a Chinatown. Mong La, Chinatown!” He laughed, and poured out glasses of sweet Taungoo wine. “All Chinese, and pagans!”