The Southeast Asian contemporary art market is booming, not only pleasing art lovers and auction houses, but also triggering rising interest from serious investors

By Jemma Galvin

As the hammer came down on Sotheby’s Hong Kong’s Modern and Contemporary Southeast Asian Paintings spring auctions in April, a record was set, cementing the region’s art market as the next ‘tiger’ of the Asian art boom.

“Our Soldiers Led Under Prince Diponegoro” by Indonesian artist S. Sudjojono (1914-1986) sold for HKD58.4 million ($7.5m) – an auction record for work by a Southeast Asian artist. The 1979 oil on canvas smashed the previous record of HKD36 million ($4.6m) set by Chinese-born Indonesian artist Lee Man Fong at Christie’s Hong Kong in November last year.

Sotheby’s, the world-renowned auction house, first started selling pieces in its Southeast Asian art category in 2001. In April last year, it sold 165 works – 96% of those it had on offer – at its Southeast Asian Modern and Contemporary art auction. The $14.5m takings caught global attention.

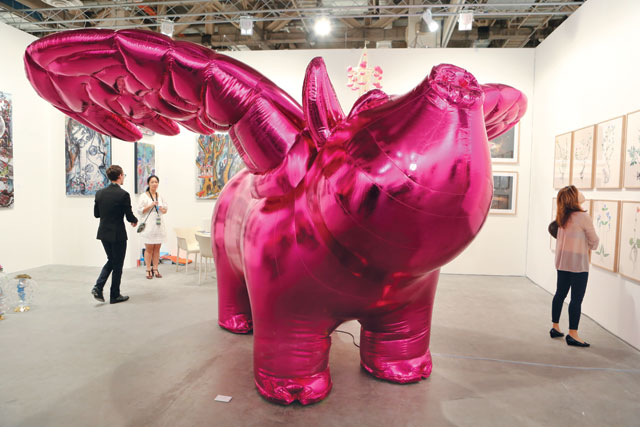

May’s Art Basel Hong Kong – where $1 billion of artwork was for sale – also highlighted further evidence of the recent global shift in the appreciation of Asian, specifically Southeast Asian, art.

Ronald Ventura, a contemporary artist from the Philippines, has been garnering staggering global attention in recent years. In 2011, his painting “Grayhound” raised HKD8.4 million ($1.1m) at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong – the most ever paid at an auction for a Southeast Asian contemporary artist.

Come this year’s Art Basel and his was some of the first work to be snapped up during the fair’s preview day, as was the work of Balinese artist I Nyoman Masriadi. The latter is, by far, the only contemporary artist who has shared the top 10% of the price chart alongside established artists such as Lee Man Fong.

The prices of his works are increasingly being seen as barometers of the health of the region’s market, and by the looks of things, it’s becoming quite the force to be reckoned with: Paul Kasmin Gallery sold a newly commissioned painting by Masriadi for $350,000 during Basel’s VIP opening.

Yet it’s not the artists, galleries or auction houses that are proving to be the major players in the growth of Southeast Asia’s art market – it’s the collectors. Educated, wealthy and regionally aware, the collectors are driving the Asian art boom that began some ten years ago when Indian and Chinese works burst onto the global stage and were snapped up by international collectors and institutions.

Singapore now has more millionaires per capita than any other city in the world, according to a study by Boston Consulting Group, and Indonesian billionaires outnumber those found in Japan, according to Forbes. Such bulging Southeast Asian wallets, combined with the strong connection between collectors and their countries’ traditions, are shaping how the region’s art will be interacted with and bought in the future.

“The strength of the art market in Southeast Asia lies in the fact that most collectors are from within the region,” says Simon Soon, a PhD student in modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art history at the University of Sydney. “This means that their collections are more focused and that long-term collectors are very knowledgeable about the development of art in the region.”

In January, Soon acted as Art Stage Singapore’s country advisor for Malaysia, as the nation was represented at the fair’s Southeast Asia Platform – a dedicated and curated sales showcase that aimed to provide a contextual understanding of the region’s art scene. It was also the place where many young and not yet established galleries, which don’t have the financial strength to rent a booth at an international fair, found the chance to present themselves to an international audience and market.

For countries such as Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, among others, the platform also addressed issues relating to deficient infrastructure that can inhibit the growth of individual art scenes.

“Southeast Asia is not lacking in strong artists, but most countries don’t have a strong and internationally competitive art infrastructure,” said Lorenzo Rudolf, Art Stage Singapore’s founder and director. “But this lack of infrastructure is not something that needs to hold the region back. Its unique geographical, economical, ecological and (cosmo)political position makes multicultural Singapore a natural choice as the necessary centre and hub of the Southeast Asian contemporary art world.”

A behemoth of an art fair, Art Stage attracted more than 40,000 visitors last year – up 25% from the 2012 gathering – and this year’s edition saw 45,700 punters file through the chilly bowels of the Marina Bay Sands Expo and Convention Centre. Hundreds of galleries, artists, curators and collectors descend on the fair to show, sell and buy the best contemporary art the region has to offer.

In attendance was Oei Hong Djien, an Indonesian former tobacco grader and the owner of the OHD Museum in Magelang, central Java. Djien, 74, has spent the past 30 years amassing an impressive collection of modern and contemporary Indonesian art, and continues to search for historical pieces to complete his comprehensive assembly of work. His collection spans more than 100 years, beginning with paintings by the Romanticist painter and pioneer of Modern Indonesian art Raden Saleh (1807-1880).

“Until recently, only Indonesian collectors collected Indonesian art,” says Djien. “But because of globalisation and the Asian art boom, Indonesia is getting increasing interest from the international art market.” So much so, in fact, that Indonesian artists and collectors are now widely regarded by scholars, auction houses and arts professionals as the most significant players in the region.

Many factors influence the who, what, when and where of art collecting. Patterns and trends emerge in line with economic tides, yet it is the human and intellectual potential of art that most industry specialists say should be at the front of a collectors’ mind when choosing a work to add to their compendium.

“Collecting is a conversation-driven process, at times requiring the buyer to step out of his or her own comfort zone to challenge his or her thinking and sensibility. After all, part of buying is also to learn a little more about the complex histories, values and ideas that inform artistic practices today,” says Soon.

However, the relative stability of art as an investment cannot be underestimated in a volatile global economic climate.

“Our art collection, in theory and on paper, has been our best-yielding investment, doing better than real estate, stocks and bonds,” explains Lito Camacho, a Harvard Business School MBA holder and the vice-chairman for Asia-Pacific at Credit Suisse AG. He and his wife Kim, both from the Philippines, have collected art since 1980 and currently reside in Singapore. “Having said that, we have only sold two pieces in 30 years. It is more of an obsession than an investment.”

No doubt, buying good art is a good investment. And if a collector is buying out of a love for the art itself, and not the love of stockpiling or selling it, it is unlikely stress or regret will follow, according to Soon.

“It is reprehensible to collect merely to shore up one’s investment portfolio,” he says. “Investment can be seen as an incentive, but should never be the driving passion that compels one to collect art. More often than not, the sad fate of artworks is that they are locked up in a temperature-controlled Singaporean warehouse, never again to see the light of day.”

Money talks, though, and figures consistently show that art – including, and perhaps especially, contemporary art – is a strong investment in terms of economic return. A major regional indicator of this was the establishment of the Southeast Asia Art Capital fund in Malaysia late last year. A private equity fund for pooling investor capital to purchase works by Southeast Asian artists, it signifies the growth of fine art markets and their ‘financialisation’. Its eventual goal is to establish a fund size of about $9.3m.

Of course, in this volatile globalised economy, it is difficult to imagine any investment being economically reliable beyond question but, according to Roger Nelson, Art Stage’s country advisor for Cambodia this year and a PhD student in contemporaneity in Cambodian art, not all investments are monetary or in opposition to the appreciation and dissemination of art for the betterment of society.

“The best thing about art as an investment is that it is also an investment in human growth – both for the buyer and for the artist,” Nelson says. “I like to think that, in general, art is an ethical investment; one that isn’t contributing to the desecration of our natural and built environments; that isn’t keeping workers’ wages low; and that isn’t displacing communities.”

Rudolf, famous for his work on Art Basel and the launch of Art Basel Miami, agrees: “Art is a way to reconnect to your inner self. It is a piece of culture – the value of it cannot be quantified.”

Events such as Art Stage and Art Basel have the infrastructure, geographical location and global reach to allow the Southeast Asian art market to achieve its huge potential. And it is the region’s collectors that hold much of the power in driving it forward.

“I see a rapidly growing interest and curiosity in contemporary art among people in the region,” Rudolf says. “The potential growth of Southeast Asian art is beyond imagination.”