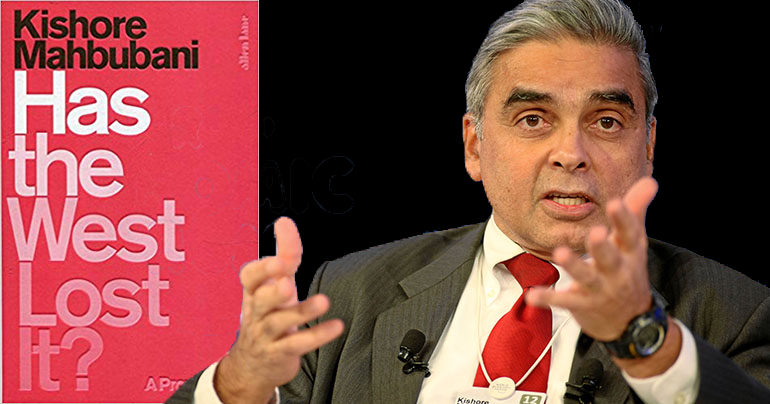

Kishore Mahbubani has written that his book is a gift to the West. That is brazen. The book he means has 106 pages and is titled Has the West Lost It? One could translate it as: Has the West lost? Or even: Has the West lost its mind? And we should be grateful for that?

Mahbubani doesn’t mean it ironically, he means it seriously. He wants to help the West, because if we continue like this, things will turn out badly for us, and for the world. His book is subtitled: “A provocation”, but there is also a threat in it; change, or else…

Kishore Mahbubani is professor of public policy at the National University of Singapore. He used to represent his country as an ambassador to the United Nations (UN). His small, massive book lays out a world order in which the West no longer dominates and China is number one.

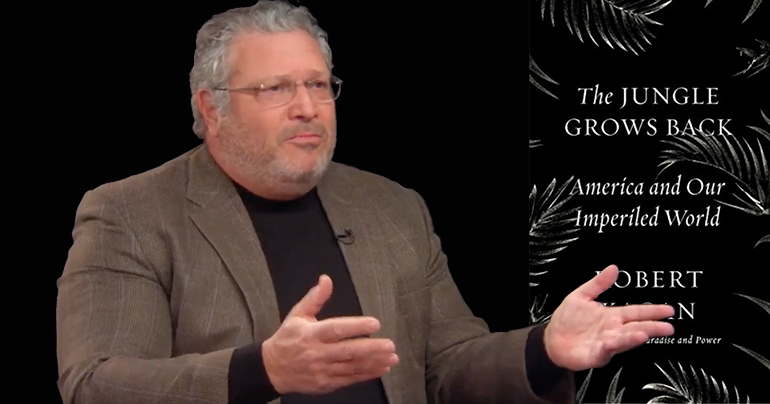

Robert Kagan thinks that this must not be allowed to happen. His most recent book is titled The Jungle Grows Back. “America and our endangered world” is the subtitle. The book has 180 pages and is just as powerful as Mahbubani’s.

The jungle, for Kagan, is the others: the non-western, authoritarian states, which disrespect human rights and are generally aggressive. They could determine the world order if the West doesn’t not resist.

Kagan is a senior fellow at the American think tank Brookings Institution and writes columns for the Washington Post.

If you read Mahbubani and Kagan together, an exciting geopolitical dialogue emerges: who will rule the future world order, China or the US-led West? And which world would be better?

Both books share the same premise: The West is on the defensive, its golden decades are over. Mahbubani sees it with some pleasure, Kagan with concern. Their narratives are fundamentally different, negative with Mahbubani, positive with Kagan. Looking into the future, it’s the other way around. Mahbubani shows himself as an optimist, Kagan as a pessimist.

Mahbubani bases his argument on numbers. For around 1,800 years, until 1820, China and India were the largest economies in the world. Then came 200 years of Western dominance, which in Mahbubani’s eyes was a “deviation” from the historical path. This phase will soon be over, China will once again be the world’s strongest economic power, and normality will return. This would historically underpin a Chinese claim to dominance.

Kagan also speaks of a “deviation”, but does not mean the economic question, but the political one: liberal order as an exception in world history.

His narrative begins a hundred years ago when many democracies emerged in Europe after World War I. The US largely left Europe on its own, and after 20 years many new democracies had turned into authoritarian states. History “led to Hitler and Stalin,” writes Kagan. The Americans had learned from this and after World War II had taken over the leadership of the West in order to create a liberal order, first for the non-Soviet part of the world, later for almost the whole world. The “more than seven decades” after World War II had been “a relative paradise”.

Mahbubani would have to laugh at this. He writes: “A painful truth that cannot be denied is that the thoughtless attempt to “export democracy” has led to increased human suffering in many countries, not diminished it.”

Kagan does not contradict him completely when he writes about American behaviour: “The result was, and could not have been otherwise, repeated failures, frustration and disillusionment, – and for some this is a fitting characterisation of the Cold War – a disastrous confusion of paranoias and moral compromises, of excesses and misjudgments, of failures and folly.”

But he stops short of agreeing with Mahbubani, suggesting that perhaps all this was unavoidable, perhaps such failures had to be accepted in order to achieve the great goal of winning the Cold War and establishing a liberal order for the whole world. This was achieved in 1989, end of story, according to American Francis Fukuyama.

For Mahbubani this attitude was incredibly arrogant and served as a salve for the West. Who says that a liberal world order, that democracy and freedom are the highest of all goals, the paradise on earth? Only the West. But history is there for everyone. And it returned, first via Islamist terrorists who bombed the West, then via authoritarian states like Russia and China, and finally via authoritarian politicians in Western states, in Poland and Hungary for example.

The liberal order crumbled, and Kagan finds this in principle just as understandable as Mahbubani, whose human image corresponds on at least one point: “Nobody is a born democrat.”

Kagan says this clearly: “The creation of a liberal order was an act of resistance against history and against human nature”. For “the people also seek order and security and could welcome a strong leader who provides all this, even if he does not grant them the full range of rights and freedoms”.

Mahbubani proclaims truths, finds things indisputable. Kagan’s arguments come from doubt, from inner contradiction, he knows of no perfect solutions, only less bad ones. If you like, this is the difference between an authoritarian and a liberal attitude.

Mahbubani would agree with this. The thesis that a need for democracy arises with increasing prosperity has certainly not been confirmed, he rejoices. Kagan admits this.

But here the sharpest contradiction between the two emerges. Kagan wants politics to fight against human nature again, wants to educate people towards liberal democracy. He clearly has a mission, a project for the whole world.

Leave the people alone with your mission, counters Mahbubani. This looks like a paradox. Kagan, the man of freedom, the liberal, wants to push humanity in a given direction. Mahbubani, who represents authoritarian Singapore, advocates freedom of choice. But what or whose freedom does he want?

“That is the greatest truth of our time,” he writes euphorically, “objectively the human condition has never been better.” He gathers together a few examples of countries that are experiencing slow but steady economic growth, Bangladesh, Pakistan and the Philippines, all of which, from a Western point of view, are rather problematic cases.

However, it cannot be denied that Asia, and China in particular, are rapidly catching up economically. Mahbubani attributes this to the “greatest gift of the West to the rest”, the power of reasoning, logic and scientific methods. Europe had long forgotten this legacy of ancient Greece, until it reappeared in the Renaissance and created the basis for European advancement.

In the meantime, according to Mahbubani, this thinking has infiltrated the rest of the world and is promoting progress in technology, the economy and politics. Most leaders in Asia have understood that good, rational governance is important, that they are accountable to their people, not the other way around.

“Whether you do this authoritatively or democratically is not so important,” Mahbubani said in an interview with Der Spiegel in 2008: “The form must fit a society and its level of development. China, for example, is not governed democratically, but responsibly.”

For Mahbubani, leaving people alone means above all leaving the rulers alone. He defends their freedom, not the freedom of the people.

He rejected the question of whether he did not believe in democracy, outraged in that conversation: “That is an evil insinuation. I really believe that all societies will decide in favour of democracy in the long term. But I don’t know when that will be. Everything takes time.”

And it needs the US, Robert Kagan would throw in at this point. Otherwise it will not be democracy that grows, but the jungle. A liberal order could only have developed “because the most powerful nation in the world since 1945 was a liberal-democratic capitalist nation.”

But this nation is on the retreat from the world. Kagan therefore takes a pessimistic view of the path of history into the future. While Mahbubani sees flowers sprouting everywhere, Kagan sees weeds. The liberal world order is “like a garden, it is constantly besieged by the forces of nature of history, the jungle, whose tendrils and weeds threaten to constantly overgrow it”. So, someone had to take care of the garden, tear out the weeds. Only the US could do that.

However, President Barack Obama has already distanced himself somewhat from this task, and Donald Trump is largely absent as a gardener. He courts the dictators and clings to a man like Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, although there is little doubt that he had journalist Jamal Khashoggi killed. Trump sometimes believes Russian President Vladimir Putin more than his own secret services. He probably toyed with the idea of leaving Nato, which in Kagan’s image, is something like the professional association of gardeners.

China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has made it clear that China aspires to equality with the United States, both as a leader and as a model for other nations. This would challenge the liberal world order through a Chinese world order.

If the US does not set the limits for the world, so Kagan’s basic thesis goes, the villains of history feel free to act evil. The relative paradise will be lost.

Moreover, another actor would push forward. China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has made it clear that China aspires to equality with the United States, both as a leader and as a model for other nations. This would challenge the liberal world order through a Chinese world order.

Not true, Mahbubani would interject here. China, “unlike America, has no messianic impulse to change the world”. The giant empire is happy to live in a “world dominated by multilateral rules and processes”.

A peaceful panda, then. But China won’t tolerate everything. “The greatest act of strategic foolishness that America could commit would be the futile attempt to hinder China’s successful development,” says Mahbubani. On the way to becoming the world’s economic number one, China will not let itself be held back.

He cleverly places a threat here, referencing a speech by Bill Clinton: a country that does not want or cannot be the number one in the world in the long run should treat all other countries in the same way as it will one day be treated by the new number one. In short: Be nice to China, or China will soon no longer be nice to you.

Kagan thinks differently. He recalls the Japanese attack on the US at the end of 1941 and hisses in the tone of the Cold War: “The Chinese must know that, although they could achieve early victories in a war with the US over Taiwan or in the South China Sea, they would wake up the sleeping giant with all its industrial power and global alliances, and in the long run they would lose”.

However, and this is Kagan’s point: the sleeping giant must wake up a second time, and it must be ready to defend the liberal order in Asia. In Europe, the same applies to Russia.

So, both authors end up on the crucial question, that of war and peace. In order to maintain global peace, Mahbubani proposes a strategy for the West – which he sees as the core of his gift to the West – the “3-M strategy”: minimalism, multilateralism, Machiavellianism.

Minimalism: The West should largely keep out, leave the others alone. “The world doesn’t have to be saved by the West, doesn’t need lessons about government structures or moral claims. It certainly doesn’t need to be bombed.”

Multilateralism: working together with the other states and, above all, accepting the UN General Assembly as the world’s most important parliament. All states are involved.

Machiavellianism: Mahbubani sees this as the ability of a society to represent its long-term interests. The West is not in a position to do so, because it can no longer assess itself and its role in the world. “[The West’s] global power is dwindling fast, but it is just continuing on autopilot”, he surmises.

In his Jungle Book, Kagan logically outlines another programme he calls “Protecting the Garden”. He doesn’t explicitly deal with the three M’s, but they also shine through in his thoughts.

Kagan thinks little of multilateralism. He considers even a multipolar world to be dangerous, since conflicts could be fought with nuclear weapons. Kagan agrees again with Mahbubani on the point of Machiavellianism. The West does not recognise exactly what its long-term interest is. In his opinion, however, this is not minimalism, but the contrary. Sometimes the West must save others, teach them, and sometimes it must bomb others.

He doesn’t write that with these words, but he means exactly that and reasons it out thoroughly. Kagan considers the authoritarian states of our time to be a more dangerous challenge than the Soviet Union and its satellites. The socialists referred to the same moral foundation as the West: the values of enlightenment. That is why utopia and reality soon came into a violent contradiction that undermined the regimes.

The authoritarian states do not have this foundation, but instead appeal to the people with basic necessities, order, strong leadership, family security, tribe and nation. China is not a communist challenge for the West, but a conservative one.

Kagan sees a long-term struggle for supremacy coming. He wants to prepare the West for this.

He wants to strengthen its alliances, especially Nato, because democracies can in principle hold together better than authoritarian states because of their common moral foundation. This advantage should not be abandoned.

The Americans would have to perceive European problems such as Brexit or the illiberal democracy in Hungary as transatlantic problems. They should return to free world trade, because it is not just about their own advantage. They should pump money into the liberal world order, as they in fact did after World War II, by nursing the young democracies in Germany and Japan. “One wonders what the Islamic world would look like if a fraction of that time, effort and resources had been used to support democratic governments there instead of promoting a chain of dictatorships,” ponders Kagan.

Then comes the delicate question: Armament? Of course, Kagan says: “Despite all the talk of ‘soft’ power and ‘smart’ power, it is ultimately the American guarantee of security, the ability to use hard power to deter and defeat potential attackers, that is the essential foundation without which the liberal world order could never survive.”

Of course, he can imagine military interventions being sometimes necessary, even at the risk of error. Those who intervene could make a mistake. But those who do not intervene can also make a mistake.

Mahbubani does not understand that. Why do Americans rely “more on bombs than brains”? Military violence has become pointless, the rest of the world will no longer accept it. “The world will become more unstable if the West does not radically change its course.”

He recommends that Europeans break away from the US and consider their own interests. Those lie in the Islamic world, if only because of the streams of refugees. He is probably right.

The overall impression when reading is as follows: Mahbubani seems calm, almost cheerful, Kagan worried, discontented. Mahbubani proclaims truths, finds things indisputable. Kagan’s arguments come from doubt, from inner contradiction, he knows of no perfect solutions, only less bad ones. If you like, this is the difference between an authoritarian and a liberal attitude.

Mahbubani is certain that with his attitude he will be the winner of history in the next round. If things go as they should, the liberal world order will disappear. China’s growth and, Kagan would add, human nature, which is so close to the authoritarian, will ensure that.

Kagan therefore does not want things to go as they should. About the American politicians of the post-war period he writes: “Even an imperfect liberal order was preferable to any order or order dominated by the opponents of liberalism”.

Is that the task now? To enforce the liberal world order on the side of the Americans, even with bombs if necessary? Or watch a Chinese world order slowly assert itself? And would that be so bad?

Mahbubani paints a paradise. Everyone living more or less peacefully together if only the West gives up its claim to dominance. But China is not harmless, as it shows internally. It is a dictatorship in which the party leadership brutally asserts its ideas and interests. Why should one trust that it would be different on the outside as soon as China feels strong enough to shape the world?

What speaks against Kagan is that its liberal world order probably needs violence to prevail. The democratic temptation itself is not strong enough. This does not mean that it cannot be made even more beautiful and seductive. But that must happen in the countries of the West.

Kagan’s approach is too offensive. It is hard to believe that the West can impose a world order against China. The goal must be a stalemate, peaceful coexistence. But it needs weapons, as a deterrent, as in the Cold War, because China is strongly arming itself. The West cannot be as trusting and euphoric as Mahbubani is. Otherwise it would have to fit into the Chinese world order, and that could be relative hell for a liberal democrat.

© 2018 Spiegel Online Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate