When the first commercial CD album was released in October 1982, Singapore’s Boat Quay was a husk of its former glory. A high-tech cargo centre in Pasir Panjang had taken over as the city-state’s main port and the tongkangs – the light, wooden boats that had plied their trade in the quay for more than a century – were no longer needed.

More than 30 years on, and following a vast redevelopment project, Boat Quay is now a bustling area of upmarket riverside bars and restaurants, located a stone’s throw from the central business district. Fittingly, it is here, on the upper floors of a non-descript shophouse, that Spotify – the world’s largest music streaming service, which has helped leave the CD outmoded in much the same way that the Pasir Panjang port left Boat Quay obsolete – opened its Asia headquarters two years ago.

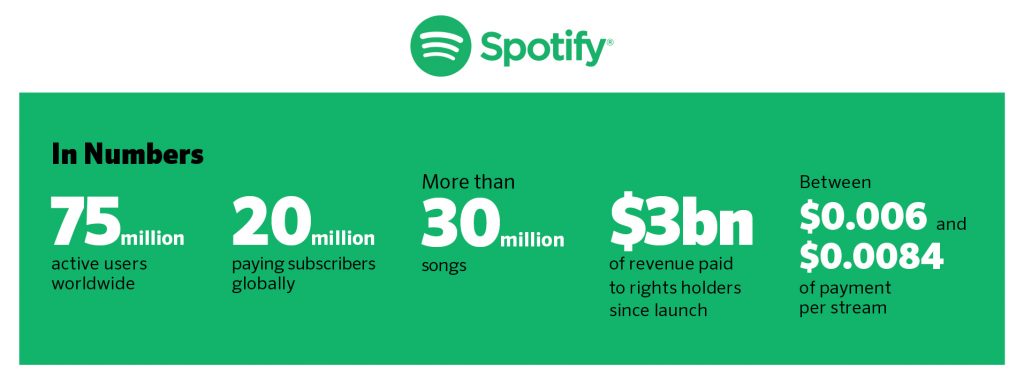

Founded in 2006 by Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, two Swedish tech entrepreneurs, Spotify launched its namesake application two years later, allowing users to legally stream free music on their computers. It soon extended to smart phones. Today, Spotify is available in 58 countries across the world, allowing 75 million users access to more than 30m songs.

Belle Baldoza, a young, bubbly PR manager, greets us at the door to give a brief tour of the Singapore office. It is everything one would expect from a youthful tech company. The design is a combination of plate-glass, wooden beams and exposed brickwork. Spotify-branded headphones and inflatable balloons are dotted around the open-plan office, where everyone seems to have the latest iMac.

There are the plush couches with candy-coloured pillows and a refrigerator stocked with energy drinks. A scoreboard on the wall charts an ongoing FIFA tournament played on a shiny new PlayStation 4. “It’s a really fun office,” says Baldoza, leading us upstairs to the meeting room. “But, of course, we are serious sometimes.”

When it entered Asia in June 2013, Spotify launched in Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong. Within three months, it had tapped into the Taiwanese market. The Philippines followed in April 2014.

Since then, there have been more than 2.5 billion music streams using Spotify in the Philippines alone – an April press release describes it as “record breaking” – and the market is said to be the company’s second-fastest growing in the world and the largest in Asia-Pacific.

Except for one or two staff members on the ground in each Asian country where Spotify operates, the rest of its workforce is based in Singapore. At the helm is Sunita Kaur, Spotify’s managing director in Asia. Before joining the music streaming giant in 2013, she had worked for Forbes.com, Microsoft and then – what Kaur jokingly describes as a “tiny, little company” – Facebook. It was music partners with Spotify, she says, so it was an easy transition to make.

The business model, Kaur explains as we sit down in the capacious meeting room, works the same in Southeast Asia as it does worldwide. Users can stream music for free, with advertising popping up between the songs, creating a revenue stream for the company. Or, for a monthly fee, users can upgrade to different packages, which are ad-free, on-demand and, more importantly for Southeast Asia, allow users to listen to their playlists offline on computers or smart phones.

“Offline playlists are a huge draw here because the WiFi connections can be a little choppy at times,” she says.

When asked if there have been any other difficulties during the brand’s introduction to the region, Kaur says with a grin, perhaps aware she’s delving into business jargon, that “there haven’t been difficulties. There have been ‘learnings’ though”.

“One of the things we did learn very quickly is that typically when someone subscribes to Spotify – so pays for an account, rather than listening for free – they do so with credit cards. But we launched in a continent where credit card penetration is low,” she adds.

They were faced with a challenge: There were hundreds of thousands of people wanting to subscribe, Kaur says, but unable to pay for it. “So we introduced other payment methods,” she said. “We needed to bridge the gap between what we offer and accessibility. We introduced retail cards so people could subscribe and, in the Philippines, we went back to old-school bank transfers.”

Another ‘learning’ that continues to affect Spotify in Southeast Asia is piracy, which Kaur notes is still “rife” in the region. The birth of the CD first gave rise to the idea of music digitalisation and the advent of the Internet allowed users to illegally ‘burn’ CDs on computers and copy songs around the world for free.

“What’s exciting is that we’re starting to see that music streaming is putting a dent in piracy,” Kaur says. In fact, a report by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry released in May found that, for the first time in four years, music sales in Singapore increased – a rise of 4.7% in 2014 compared to the previous year.

Sales of physical copies – CDs, for example – remained low. It was digital music that was behind the increase. It also found that music streaming services, such as Spotify, were an important factor behind weakening music piracy.

“We were all joking that we sit behind our desks, squirreling away,” Kaur says, “so it’s really nice to see something like that, because it shows what we do, it is paying off… Money is going back to the artists, which is essentially why Spotify is here.”

According to Kaur, one of the major goals of the business is to help nurture local talent and to bring their music to the entire world. Two of Spotify’s unique features are key. The first is Browse, which provides subscribers with playlists of music trending in their country, introducing them to new, local artists. The second is Discover Weekly, a two-hour playlist, released every Monday, made up of music that Spotify thinks you’ll like.

In the Philippines, they have made a great effort to support what is known as ‘Original Pilipino music’ (OPM). This year, Spotify also announced it would hold its first Spotify Sessions – exclusive, live performances in the Philippines to support local artists.

“We also do a lot of partnerships – it’s in our DNA,” Kaur continues. “We would rather partner than build as it really helps with keeping the music community alive.” For example, in April, Spotify teamed up with The Music Run, a five kilometre fun-run in Singapore. They allowed participants to vote for the playlists that would be featured during the event.

A few minutes later, our interview is finished and in her place sits Chee Meng Tan. He is Spotify’s director of label relations for Asia-Pacific. This means he is in charge of liaising with the record labels, recording associations and artists to help them promote their music and to, as he puts it, “monetise their assets with Spotify”.

“I work across the entire ecosystem,” he says. “We license the content from the rights holders – record labels, music publishers, artists – and I work very closely with the artists and their managers.”

However, the company has not been immune to criticism over how it treats artists. Spotify operates by paying record labels or artists royalties of between $0.006 and $0.0084 ‘per stream’ depending on their country of origin. Over the years, members of famous bands such as Radiohead, the Black Keys and Talking Heads have said that the service does not pay artists enough and, in 2014, Taylor Swift pulled her entire catalogue from Spotify for similar reasons.

Tan is, nevertheless, unperturbed and believes Spotify does well for musicians in Southeast Asia. He says that, on average, the company pays 70% of its revenue to labels and publishers. According to Spotify’s website, from its launch until now the company had paid more than $3 billion in royalties.

In May, the Guardian newspaper reported that the company’s 2014 financial records showed that, despite surpassing $1 billion in revenue, it recorded a net loss of almost $190m. Yet the company emphasises that both revenues and subscribers are on the rise.

“2014 was definitely a transformative year for us, with the successful transition from desktop to mobile, ending in a record-breaking quarter for subscriber growth. We now have over 75 million active users and 20 million paying subscribers globally. We also saw a significant increase in revenues – 45% year-on-year,” says Kaur. “We’re focused on growing the business and in this process have made some substantial investments during the year, mostly in product development, international expansion and increase in personnel.”

Working in different countries can also have its challenges. Some labels are very large and have 30 or 40 years’ experience in the industry, while others are relatively new, with just a few artists signed up.

“Everyone is embracing music streaming and it’s inevitable they’ll have to move in that direction,” Tan says. “But there are certain markets where physical music is still dominant and the artists would like to see their CDs on the shelves in shops. One of the difficulties for a record label is how to keep that physical business while transitioning to the digital.”

Education, he says, is the answer. His work is often about helping artists and record labels understand that they can profit by moving from the “one-off transaction model” – a customer buying a single CD in a shop – to the continual streaming model used by Spotify, which allows them to look “at the lifetime value of their work”.

“I have just got back from the Philippines,” he continues, “and we ran workshops with the local recording associations and artists. I was helping them understand how to make full use of Spotify, how to build connections with their listeners and then convert them into fans. Basically, how to unlock the full value [of their music].”

Tan is optimistic about the future. If the statistics are anything to go by, he has good reasons to be so. Last year, he says, the Philippines saw digital music sales overtake physical. “Maybe that’s because we launched there,” he jokes. Then there’s the fact that one out of every five Filipinos with internet access is using Spotify. Then, there is Southeast Asia’s youthful population. “Our profile users, they’re mainly between 18 and 35 years old. Millennials. So Asia presents a phenomenal growth.”

There is also the fact that the profusion of devices capable of using Spotify is growing in the region. “We want to be platform agnostic,” Kaur says, meaning that Spotify operates on iOS, Android and Windows. “We can track which devices are strongest in different markets. In the US, iOS is huge. But in Southeast Asia, it’s mainly Android. And, which is good news for us, these devices are becoming more accessible and affordable.”

And such optimism extends to Spotify’s future in Southeast Asia. “We have 58 countries now and that’ll grow,” she adds. “It’s definitely easier to move to different countries now we’ve had the practise, and we’re at the point where we have a lot of demand – Thailand, Indonesia, even maybe Cambodia. We want to be everywhere.”