With the woods required to craft guitars in dangerously high demand, an experienced yet enterprising Yangon luthier is championing sonic sustainability by utilising obscure local timbers

“I think I came into the world to make guitars,” Ko Cho says, sitting outside his modest home in northern Yangon. “When I’m sleeping, I’m thinking about guitars; when I’m eating, I’m thinking about guitars.”

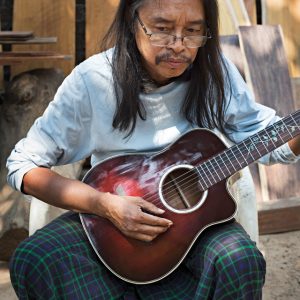

a self-taught luthier with

a big reputation in Yangon. Photo: Andre Malerba

As he moves his fingers up and down the fretboard, while gently plucking the strings, a sweet smile widens across his face, making him appear younger than his 62 years.

Ko Cho’s love affair with the instrument began decades ago when, as a teenager, he was given his first custom-built guitar by his parents. A luthier who lived on the same street had been commissioned to make it, and a young Ko Cho was fascinated by the way the craftsman bent and shaped the wood. Ko Cho often visited the luthier, watching as he carved the wood into form.

After travelling the world as a merchant seaman for 20 years, Ko Cho decided in 1993 that he needed a new direction. “I’d had this dream to make guitars since I was a kid, but I thought of it again and again while I was at sea,” he says.

He eventually returned to his native Yangon in 1998, opening a small guitar store and workshop downtown. Slowly, Ko Cho’s reputation grew by word of mouth. His clients now range from beginner guitar hacks to some of Myanmar’s most famous rockers, such as Zaw Win Htut and Myo Gyi of Iron Cross fame.

But it is the local timbers he uses that sets Ko Cho apart from other luthiers in more established guitar-producing nations such as the US. The materials that he works with are unconventional tone woods that have a surprising depth of sound and tone, yet they are also unique and durable.

Entirely self taught, apart from those visits to the local luthier as a child, Ko Cho learned his craft by trial and error. In the industry, luthiers are generally limited to a few types of tone woods. The tops of the guitars are made of softwoods such as spruce, with the backs and sides made from denser, harder woods such as mahogany and rosewood.

Of all the tone woods, mahogany is probably the most versatile, and it is sometimes also used for the soundboard (front) and in necks due to its lighter weight. A timber’s colour is also significant, and mahogany is revered for its lustrous dark-pink to magenta hues that lend a unique character to the instruments.

While softwoods such as spruce are difficult to acquire in Southeast Asia, luthiers in North America can rely on exotic hardwoods from throughout the world: mahogany from Honduras, rosewood from India and cedar from Alaska. Teak is also prized but rarely used as it is difficult to obtain.

However, these popular tone woods are becoming increasingly rare and overharvested, posing a problem for luthiers the world over. Ko Cho has met the dilemma head on and made it his goal to find as many indigenous tone woods as possible.

“I thought about my country and what is available here,” he explains. “In fact we have many resources. Everything we make at the workshop, I’ve researched and combined from local woods. I’ve found 19 tone woods here in Myanmar. It wasn’t easy to find, so I’m very happy that I can share these precious things with the world.”

Among his most exciting discoveries is the East Indian Walnut. Found just about everywhere in the Yangon region, the wood is versatile with a warm timbre and volume somewhere between a rosewood and a mahogany. Ko Cho has also experimented with jackfruit, which he says is a reliable hardwood and produces good volume in acoustic guitars.

There are some species that he finds hard to name in English. The “Yamini” tree is found in Myanmar and some parts of India. Its colour is a pale yellow which, when sanded back and varnished, looks almost like a creamy spruce or cedar. The density of the softwood is perfect to use as a soundboard for a classical guitar with nylon strings, Ko Cho says.

The relative abundance of the woods he uses is not only good news for the environment; it also means he is able to keep prices low. “Economically, these trees are better than teak or rosewood, which also grows locally,” he says.

Ko Cho has taken his sustainable practices even further and regularly salvages second-hand wood from renovated houses and is a regular client at plantations around Myanmar. He even managed to salvage timber from felled trees and the wooden steps of a destroyed monastery in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis in 2008.

Back in his merchant seaman days, Ko Cho visited many guitar stores only to find the prices prohibitively high. Thus it has always been important to him to craft inexpensive guitars that are made to be played. “I never think about [becoming rich]. I think about making guitars; good guitars. That’s all,” he says.

As he speaks, Ko Cho hands over the guitar he’s been strumming to its patiently waiting new owner. “This is a really good guitar,” Ko Cho mutters to me quietly. “I don’t really want to give it to him.”

Keep reading:

“Vice city: Myanmar” – From flagrant prostitution to brazen wildlife hawking, Southeast Asia Globe explores Mong La, one of the region’s most lawless towns