Following the death of King Bhumibol Adulyadej, leadership of Thailand’s monarchy has automatically passed to Privy Council president Prem Tinsulanonda. As regent, the controversial figure will have a decisive stake in the country’s politics

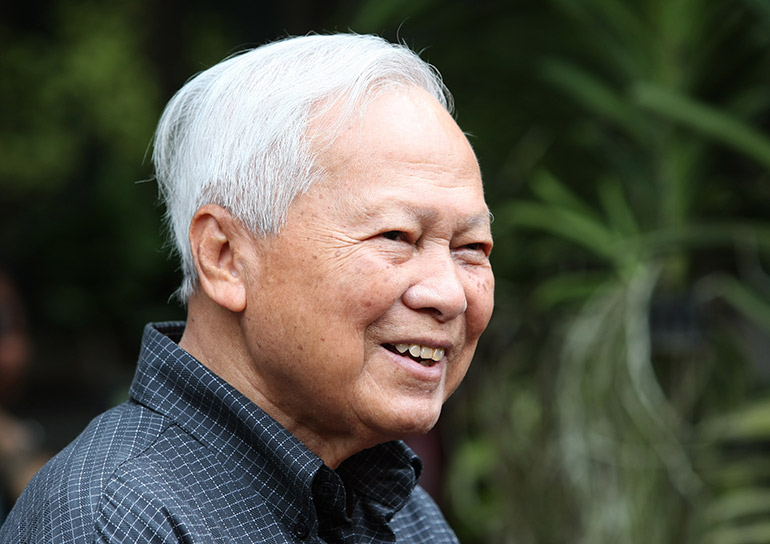

While Thailand continues to mourn the death of King Bhumibol Adulyadej, attention has turned to Prem Tinsulanonda, the divisive former prime minister and military general that has assumed the role of regent.

There has been no formal announcement of the 96-year-old’s appointment to the position. But, under the Thai constitution, he is automatically granted the role due to his place at the head of the Privy Council, a group of advisors appointed by the king that has notable powers concerning royal appointments and the law of succession.

On Friday evening, Deputy Prime Minister Wissanu Krea-ngam made an announcement, without explicitly mentioning Prem’s name, in which he said that control of the monarchy would pass to the regent.

“There must be a regent for the time being in order not to create a gap,” Wissanu was quoted by Thai media as saying. “This situation will not be used for long,” he added.

In the days immediately following Bhumibol’s death, the status of Thailand’s leadership remained up in the air.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha told reporters on Thursday that Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn did not wish to be immediately named king. “He said at present, he is the heir apparent. But he would like to take some time to mourn together with the people of Thailand,” Prayuth said.

And in a televised address on Saturday, Prayuth told the nation that the crown prince’s coronation would be delayed until after the mandated year-long mourning period. Vajiralongkorn “asked the people not to be confused or worry about the country’s administration or even about the succession”, Prayuth said in his statement.

“He said at this time everyone is sad, he is still sad, so every side should wait until we pass this sad time.”

According to Andrew MacGregor Marshall, a British journalist who has written extensively on the Thai monarchy, the coronation’s delay is proof that a tense power struggle is being waged in the upper echelons of the country’s government.

“Information from multiple sources with links to the palace and the extended royal family suggests that a secret struggle over royal succession that has simmered beneath the surface of Thai politics for years is not yet over – and this is why Vajiralongkorn has not yet been proclaimed king,” he wrote today. “In particular, the scheming 96-year-old royalist former general Prem Tinsulanonda is trying to force the crown prince to accept curbs on his rule.”

Prem had been pushing for Vajiralongkorn’s sister, Crown Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, to be named next monarch, Marshall added. Although unprecedented, as a woman has never reigned during the Chakri dynasty, a constitutional amendment in the 1970s does allow a woman to occupy the throne. However, according to Marshal, both Vajiralongkorn and Prayuth rejected the plan and Prem is now pushing for Sirindhorn to be uparaja, or deputy monarch, to act as a curb on Vajiralongkorn.

Prem and Vajiralongkorn, who is widely disliked within Thailand, have a well-publicised history of animosity, with the former being accused of masterminding the 2006 coup that deposed then- prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who has a close relationship to Vajiralongkorn.

Paul Chambers, a lecturer of international relations at the Institute of Southeast Asian Affairs in Chiang Mai, said Prem’s role in that coup is telling of his potential to sway the course of Thai politics. “It means that he has the experience, following in the army, and possible intention to make and break Thai governments,” Chambers said. “His role in that coup also showed him as an arch-royalist anti-Thaksinite. Thaksin has no place in Prem’s arch-royalist narrative. Such a narrative may not agree with that of the newly ascendant monarch.”

Prem began his career in the military, joining in 1941 and serving in the country’s short war with France over Cambodian territory. His first political position came in 1959, when the general was part of a committee to draft one of the country’s 20 constitutions that it has had since 1932.

He later served as a senator and eventually as a deputy interior minister. His relationship with Bhumibol grew closer when he served as a royal aide-de-camp in the palace both in 1968 and 1975. After serving as prime minister for eight years from 1980, he was appointed president of the Privy Council in 1988.

His rule as unelected prime minister during the 1980s was typified by ‘Premocracy’, a semi-democratic iteration of government where “elected politicians and political parties could contest polls and divide up [less powerful] ministries”, wrote Thai political scientist Thitinan Pongsudhirak in the Bangkok Post earlier this year.

But Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, argued that Thailand would likely not see a return to this ‘Premocracy’, as the country’s ruling military junta is currently the country’s true bastion of power.

“He can’t instil anything as regent of the monarchy, other than help – with a group of people – decide the next monarch,” Kurlantzick said. “This is very important in Thailand, but it’s not ‘Premocracy’. He’s not running the country. The junta – and then next year after elections some hybrid government likely – is running the country.”

Still, as mourners clad in black lined the streets of Bangkok for Buddhist funeral ceremonies that began last weekend, the extent of the new regent’s power – and the future of Thailand’s monarchy – were both unclear.

With regent taking place of King, Thailand’s future looks uncertain

Following the death of King Bhumibol Adulyadej, leadership of Thailand’s monarchy has automatically passed to Privy Council president Prem Tinsulanonda. As regent, the controversial figure will have a decisive stake in the country’s politics