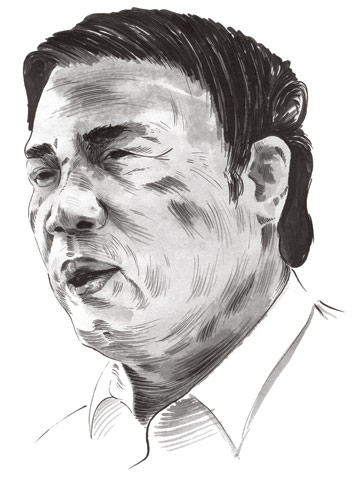

Despite being brought into the fold of Vietnam’s high-ranking officials to help weed out corruption, Nguyen Ba Thanh is no stranger to underhand dealings

By Sacha Passi

If ‘absolute power corrupts absolutely’, as British historian and moralist Lord Acton famously stated in 1887, then it may come as no surprise to some that Vietnam’s one-party communist government is riddled with infighting and political corruption.

“The problem in Vietnam is that no party or state entities are truly autonomous and independent. Corruption runs through the body politic like blood through veins,” said Carlyle Thayer, an emeritus professor at the Australian Defence Force Academy in Canberra.

Efforts to eradicate endemic corruption and improve governance by Vietnam’s Communist Party (VCP) have been mixed, and generally proven futile.

In 2006 Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung set up the Central Steering Committee for Anti-corruption, appointing himself as the head. Under Tan Dung’s watch corruption increased – a development that has been linked to a stagnating economy and a string of high-profile scandals, including corruption within state-owned enterprises.

A native to Danang on the central coast of Vietnam, Ba Thanh had led the centrally administered city since 2003, until he was given a leadership position in Hanoi in January. The former chairman of Danang Municipal People’s Committee is credited with transforming the once-poor town into one of Vietnam’s most liveable cities and a viable hub for investors. His hardline attitude towards corruption and ability to attract foreign investors has earned him a reputation as a decisive and visionary administrator.

A survey conducted by the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry in 2012 found that at least half of its members have paid bribes to state officials. The prime minister’s inability to curb underhand dealings almost saw him unseated in November.

“We have seen repeated protestations by Vietnamese leaders to clean up the system, but the problem is the VCP itself,” said Frederick Brown, a visiting scholar with Johns Hopkins University’s SAIS Southeast Asia studies programme. “Corruption is bound up with the VCP’s ingrained fear of power sharing, which would mean the rise of political opposition – that is a no-no for the communist power structure,” Brown said.

Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index shows that worldwide confidence in the country is in steady decline. Between 2011 and 2012, Vietnam dropped 11 points in the index, coming in 123rd out of 174 countries.

In a bid to quell outside criticism of a tarnished political system the VCP has made gains in strengthening its anti-corruption framework. Notably, the Politburo, the highest-ranking body of the VCP, has introduced the Central Internal Affairs Commission – an advisory board designed to investigate corruption within its own ranks and advise party groups such as the Central Steering Committee for Anti-corruption.

Heading the commission is former Danang City party chief, Nguyen Ba Thanh, who has the power to pursue and hold high-ranking officials accountable for corruption. However, the 59-year-old will be expected to toe the party line.

“In the end all recommendations made by Mr Ba Thanh have to be approved by the Politburo… and any deliberations will be made mainly on political, not legal, grounds,” Thayer said.

Ba Thanh is a controversial figure in Vietnam, receiving praise for the rapid development of Danang and criticism for his dictatorial style of governance.

Despite his general reputation as a respected and powerful leader, Ba Thanh has been unable to avoid accusations of corruption. In 2000 he was implicated in a major corruption case in which he was accused of receiving bribes linked to the construction of the Han River Bridge project in Danang. The contractor, who admitted to police that he had bribed Ba Thanh, was sentenced to 13 years in prison. Ba Thanh’s involvement in the matter has not been pursued.

“Ba Thanh has been mentioned in various party and government reports for his alleged corrupt activities. None of this mud has stuck,” Thayer said. “In Vietnam the ‘right’ person for the job is not necessarily the individual with the best merit-based qualifications but the person who has friends in high places.”

The appointment of Ba Thanh demonstrates much needed ‘political will’ by Vietnam’s leaders to reduce corruption, but whether the country will follow through is yet to be seen.

“Any concerted attempts to end massive corruption across the board would quickly lead into networks of interests and patronage,” said Thayer. “The best Vietnam can do is address high profile cases and pick a few sacrificial lambs.”

Related Articles

“Sibling Rivalry” – After five years sitting on the sidelines of Thai politics, Yaowapa Wongsawat could soon find herself appointed Thailand’s next prime minister