Amid the hissing and pops of a 108-year-old recording, a woman’s voice emerges. Halfway through, a wind instrument erupts into what sounds almost like a free-jazz solo, before the woman’s voice returns, cracking with emotion as she completes the song.

That this recording of “The Grand Yodaya Song” by Burmese ensemble Yodaya Bwe Gyi – cut in 1906 – survives is remarkable. “They [78rpm records] are extremely breakable, difficult to carry and ship and are often found in terrible condition,” says Jonathan Ward, an engineer on the Longing for the Past: The 78rpm Era in Southeast Asia project. And the problems don’t end there. “Southeast Asian climates are not kind to shellac. It is very susceptible to the effects of mildew and mould,” says David Murray, who curated the release of the four discs and hardcover book for the Dust to Digital label. “It’s very difficult to find 78s in good condition in Southeast Asia.”

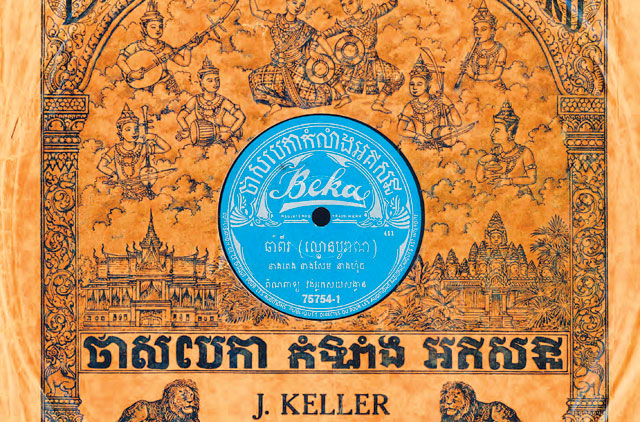

The story of music recording in the region began in the early years of the last century. Having already penetrated markets in Europe and the US, record companies began looking further afield and sent representatives to record the music they discovered along the way.

The first foray into Southeast Asia was made in 1902 by a recording engineer from the British Gramophone Company named Frederic Gaisburg. At first, the wax-cylinder recordings were sent back to Europe, records were pressed and some were then shipped back to the region. By 1908 the company had built a pressing plant and gramophone manufacturing facility in India, which served the region for a while.

Initially, the companies had no real plan: They were simply testing the musical waters to see what would sell. Locals must have been intrigued by the strange foreigners lugging unwieldy recording equipment that looked like a cross between a French horn and a sewing machine. But what they recorded inadvertently became an archive of music that would otherwise have been lost to posterity.

Eventually, recordings became more tailored to the tastes of local audiences and entrepreneurs set up their own labels, albeit using the major labels’ equipment in the region and pressing the records in Europe.

“In those days, natives of the countries where we set up our temporary laboratories wanted records of their songs, their bands and storytellers,” said Harry Marker, a recording engineer for Columbia Records from 1905 to 1930 who is quoted in the book accompanying the release. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, labels sprung up all around the region, notably in Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

The fact that some records were pressed in Europe has been a boon for modern-day collectors of rare discs. “Some of my best records of Vietnamese or Cambodian music were located in France, where they had originally been pressed,” says Murray. “At first, records were recorded in Southeast Asia and then sent back to Europe for production. Some stayed in Europe if there were large enough Southeast Asian communities. One friend of mine even found a few Cambodian 78s in Morocco.”

According to Murray, there is not much interest in the music in present-day Southeast Asia. “I have a feeling that much of this music is old enough that the average person would have a hard time relating,” he says.

Jason Gibbs, an expert on Vietnamese music who contributed to the project, agrees. “There is presently a bias in Vietnam against music that does not sound cleanly recorded and presented,” he says. “They [78s] would be difficult listening for a lot of Vietnamese today.”

Without the efforts of people such as Murray, music from this era would exist only in the living rooms of collectors. “When music like this is curated and presented in a format such as Longing for the Past, it becomes more accessible,” says Murray.

It was no small task for the team to render the music acceptable to modern ears. “They [78s] are often subject to excessive noise reduction when reissued on CD,” says Murray. “While they end up with less audible surface noise, they have a terrible muffled quality because some of the frequencies that belonged to the music are removed with the noise.”

Once records for potential release were selected, Ward cleaned them and began the process of transferring them to digital format. This is where the fun began. “There are all kinds of problems at the transfer level: warps, off-centre spindle holes, bad pressings, heavy wear,” says Ward. “The groove widths on 78s vary greatly, especially when you’re talking about 78s made by local labels in Southeast Asia.”

To counter the problematic grooves, a special ‘truncated’ stylus – a needle with the tip removed – was used. The truncated tip is important as, with old 78s, the bottom of the groove containing the sound is usually worn from years of being played and can translate audibly as noise. A truncated stylus allows the needle to ride a little higher in the groove, thus avoiding the obstructions at the bottom.

Using specialist recording equipment, Ward made the digital transfers and sent them on to Michael Graves, a Grammy Award-winning mastering engineer, who eliminated noise using professional software. These programmes are not without their limitations, however, and some unwanted noises can remain.

“The only way to deal with this is to manually remove the offending noises in the computer,” says Graves. “This is a painstaking process, but the results can be astonishing.”

Although 90 tracks from the era may sound a lot, it’s only scratching the surface of the recorded musical output of Southeast Asia in the first decades of the last century. The rigours of climate and the ages combine with a lack of accurate records to make the enthusiast’s job a hard one.

“It’s difficult to know what’s been lost because we really don’t know the scope of all the recordings,” says Murray.

However, he will keep on looking. It’s a labour of love.

“I try to figure out the story behind the records: who recorded them and when, who were the artists, why certain styles were recorded and not others,” he says. “I’m interested in putting together the pieces of the puzzle.”