Tricked, abused and nearly killed, a victim of Cambodia’s human trafficking uses art as a therapeutic outlet

By Sarah Thust Photography by Heiko Tremmel

When Vannak Prum dreams of the sea, he envisions himself swimming alone in the middle of the ocean, with no prospect of rescue. He invariably wakes soon afterwards, drenched in sweat.

A restful night is only possible once he discovers the reassuring presence of his wife, Srey Khem, breathing next to him. For four years, this former slave was denied the love of his partner, yet now he externalises his experiences, expressing them on a sheet of paper.

“For two years, I could not find work in Pursat province. The NGO Licadho motivated me to start drawing my experiences as a victim of human trafficking,” Vannak Prum says, while adding detail to his latest work. The 35-year-old hopes to become a professional painter and, squatting in a small wooden hut near Wat Bakan, he explains how his artwork depicting his forced labour for a Thai commercial fishing fleet has “helped me to overcome this time full of pain and suffering”.

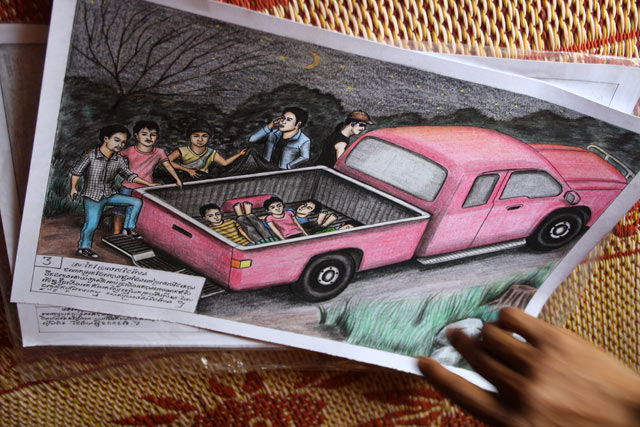

In June 2006, feeling under pressure to earn money for his unborn child, Vannak Prum left his pregnant wife to work on a farm near the Thai border. With little money coming in, he jumped at a new job opportunity in a Thai fish-processing factory, but after days of travelling he was instead forced onto a Thai fishing vessel.

Beatings were common, as were 20-hour working days, and the promised monthly salary of 4,500 baht ($140) was nowhere to be seen. Elder workers were forced to take drugs to enable them to stand the hard work. “At the beginning I felt bad because I worried about my family. But when I saw other workers committing suicide I decided to focus on work,” says Vannak Prum.

For three years, he experienced mistreatment, hunger and solitude. But with the help of a Cambodian captain on the boat, Vannak Prum and another Cambodian jumped ship near Sarawak, Malaysia and swam 20 minutes to shore. His freedom did not last long, however, as he was soon picked up by another broker. “He looked like a policeman and told me that I had to earn money to return to Cambodia,” remembers Vannak Prum.

He was soon put to work on a palm oil plantation, weeding, planting and harvesting alongside other victims from Indonesia, Thailand, Myanmar and one fellow Cambodian. “They paid the Thais and the Indonesians, but we received only $10 from time to time,” he says.

Four months later, the situation escalated. When two drunken workers attacked each other with machetes, Vannak Prum and his Cambodian colleague intervened. Vannak Prum received a vicious stroke to the neck, and his friend a serious head injury. To avoid problems, the plantation owner dropped them along a deserted road at night.

Although the men found their way to a hospital where they recovered from their injuries, a seven-month prison term was handed down under Malaysia’s draconian illegal entry laws.

Finally, in May 2010, Licadho freed Vannak Prum and brought him home. In all those years, his family had received no news from him, his wife having to work on rice fields for $2.50 a day. Far from the long lost embrace of a loving family, mistrust and scepticism were all that greeted Vannak Prum when he returned to his village in Pursat.

“My wife and her parents thought I married another woman in Thailand. They did not believe my story until someone from Licadho confirmed it,” he remembers.

Vannak Prum is yet to overcome what happened to him in Thailand and Malaysia. Nightmares and insomnia are regular visitors in the wee hours, as is a fear of leaving his family alone. “Over all those years I tried to imagine what my daughter is like,” he remembers. “The picture of my wife and my newborn was always in my mind. I was so excited when I saw my daughter [for the first time] and I never want to leave them again.”

His wooden home has become his de facto studio, with the therapeutic outlet of painting playing a key role in his recovery. Painting for a living is the dream, but for now Vannak Prum remains plagued by self-doubt. “I don’t dare to sell my pictures on the market because I don’t have proper tools and supplies to paint. Other artists can deliver high quality, but I never got trained at all,” he says.

Vannak Prum’s pictures have helped to identify his exploiters, even if they faced no consequences, and Licadho continues to support his work. For now, though, this unfortunate man with natural talent continues to craft images depicting the violent truth of life on Southeast Asia’s margins.

“It doesn’t matter whether I draw landscapes, portraits or my history,” says Vannak Prum. “Afterwards I feel relieved and free.”

Also view

“The canes of wrath” – There is nothing sweet about life for the exploited labourers of Cambodia’s sugar fields