Children in Malaysia have been labelled the fattest in the region, but their weight carries a greater burden than just their size

by Sacha Passi

‘Globesity’ is a growing problem often associated with the riches of the developed world but, as the term coined to describe the global spike in obesity and diet-related diseases suggests, the phenomenon is making few exceptions.

In Southeast Asia – a region still grappling with the challenges of malnutrition – Malaysia has earned the inglorious title of the region’s fattest nation, and the sixth most obese country in Asia. Between 2006-2011 the country recorded a 14% rise in obesity among people aged 18 and above, counting 2.6 million obese adults in the country by 2011.

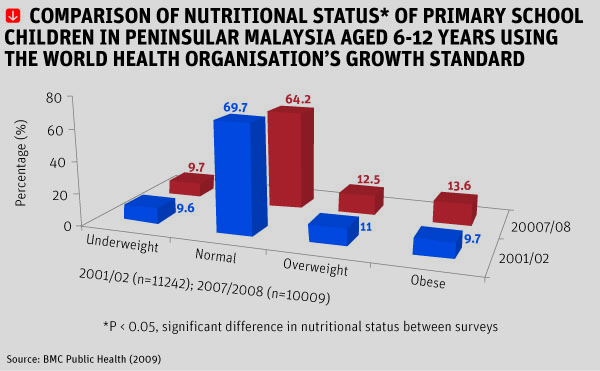

What is perhaps more worrying is that Malaysia has undergone a transition from under-nutrition to relative over-nutrition within a period of three decades. In April 2012, a survey by the Ministry of Health revealed that just over a quarter of Malaysian school children were obese or overweight.

“Developing countries, such as Malaysia, face a ‘double burden’ syndrome. While we are still grappling [with] the problem of under-nutrition, prevalence of obesity has clearly increased in the past decade,” said Dr Mohd Ismail Noor, president of the Malaysian Association for the Study of Obesity (Maso). “In fact, in countries like Malaysia, there are more overweight/obese children than underweight counterparts. What’s more striking, the prevalence in rural areas is as bad as those children living in urban areas.”

Noor adds that irrespective of age, ethnic and social status, the prevalence of obesity is largely a result of rapid development in Malaysia. “As our economy grows – one of the fastest in the region – food shortage is basically unheard of. The accelerated phase of industrialisation and urbanisation in recent decades has inevitably brought changes to our lifestyle.”

With strong economic growth, a relatively stable government and free trade, Malaysia is on track to become a developed nation by 2020. Furthermore, the Asian Development Bank states that the country’s achievements in battling poverty and improving enrollment in primary education, gender equality, and access to healthcare services are well ahead of the 2015 target.

Lifestyle choices, genetic predisposition, learned behaviour and a lack of health awareness are all known contributors to growing numbers of obesity and overweight populations.

The fact that obese children are more likely to become obese adults, and the connection between obesity and chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer is not lost on the Malaysian government.

In 2011 the local government introduced an initiative for school report cards to include a student’s Body Mass Index (BMI) – a number calculated using height and weight measurements to determine whether a person falls within a healthy weight percentile – as a way for teachers and parents to monitor a child’s health. Under the initiative, students with unhealthy BMIs are referred to government clinics and given counselling on healthy living. Implementation of the programme however has fallen under the discretion of individual teachers, and is loosely applied across the country.

“I’ve heard stories where teachers just sit at their desk and ask the children to ‘shout-out’ their weight,” said Noor. “In short, it is a good initiative but how well it is being implemented is anyone’s guess.”

In January 2013, Health Minister Datuk Seri Liow Tiong Lai, again stepped up the battle of obesity in schools with the introduction of a ‘healthy lifestyle with skipping’ initiative to encourage children to become more active with the distribution of skipping ropes to 200 schools nationwide.

The most basic determinant of excess weight is a simple imbalance between calories consumed and calories expended. The fact that adults worldwide are struggling to grasp the concept is particularly concerning when their responsibility becomes raising healthy children.

“[Malaysian] parents should pay greater attention to monitoring the meals of their children. In many families both parents are working and very often this aspect is neglected,” Dr E Siong Tee, president of the Nutrition Society of Malaysia, said. “Children skip breakfast… meals are high in meat, fat, salt and low in vegetables and fruits. Sugary drinks including soft drinks, cordials and syrups are another popular group for children, [as are] sweet cakes and local snacks.”

Many energy-dense foods are nutrient poor, taste good and are readily available in Malaysia. With more than 500 KFC outlets in the country, the international company dominates Malaysia’s fast food sector, marking a 41% share of industry sales in 2011. Furthermore, charitable initiatives such as KFC’s Projek Penyayang, which donates meals to over 6,500 children each year in an effort to enable “thousands of orphans and underprivileged children to enjoy KFC meals”, seems a misguided concept considering the country’s current battle with the bulge.

On average, a healthy nine-year-old requires approximately 1,800 calories a day. Two pieces of fried chicken, mashed potato and a soft drink can total 1,300 calories – or just under three-quarters of the child’s total recommended daily energy intake.

A diet of fast food is high in energy and low in nutrition, proving a double-edged sword for the needs of a growing child.

“A good nutritional start is vital for children to grow and develop optimally, and to be able to achieve well academically,” Tee said. “Prevention of obesity and other chronic diseases must start from a young age.”

The implications of a prolonged lack of nutrition are serious for growing bodies, and are a known precursor for hindered brain development and intellectual capacity, as well as posing a potential risk for irreversible stunting of physical growth.

In Malaysia, widespread calcium deficiency in children is cause for concern, as is the fact that almost one in two children are low in vitamin D, based on the Recommended Nutrient Intakes (RNI) as outlined by the Malaysian Ministry of Health. Both are essential components for growth and development, but deficiency is also easily preventable.

The recommended calcium intake for a child aged from nine years is 1,300 milligrams per day, which can be achieved with the introduction of foods such as tofu, yoghurt and cheese to a child’s diet.

Additionally, vitamin D deficiency is easily alleviated through adequate exposure to sunlight, but Tee says an increasingly sedentary lifestyle led by Malaysian children is another challenge.

“School children are just too tied down with school work, homework, tuition classes and extra curricular classes that they do not have the time and opportunity to do outdoor activities, such as games and sports,” Tee said.

The physical burdens of excess weight are worrisome, but the mental impact of carrying extra weight, such as peer isolation and the development of low self-esteem in Malaysia’s youth, also cannot be ignored.

Fundamentally, what differentiates adult obesity and childhood obesity worldwide is that grown-ups choose the lifestyle they lead, whereas children are destined to follow the path adults tread before them.

Malaysia is no doubt reaping the benefits of rapid development, but it is also feeling the additional burden of curbing a trend that the majority of the developed world has found difficult to reverse.

Related Articles:

“Fat Under Fire” – With the number of overweight and obese people swelling at an alarming rate, have governments left it too late to fight the flab?