In the darkened room, a woman lounges nude before a curious audience.

Different screens lay her body bare from all angles: on one, her penis rests between her thighs for all to see. Another frame traces the curve of her body against a couch, the silhouette of a feminine form against the empty space of the room in which she rested when filmed in black-and-white by Thai artist Arin Rungjang.

Rungjang submitted the video art piece as his contribution to the Spectrosynthesis II exhibition at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center (BACC), a grand, seashell-like building in the city’s central shopping district. The exhibition, subtitled Exposure of Tolerance: LGBTQ in Southeast Asia, was billed by its organisers at the Hong-Kong-based Sunpride Foundation as the largest-ever survey of contemporary queer art from Southeast Asia and beyond.

Gay himself, Rungjang sat in the exhibition hall to explain the motivation of his piece. Behind him were a series of traditional Chinese paper-cuttings depicting their creators’ coming-out story in colourful, fantasy imagery that seemed befitting of a fairy tale. Before Rungjang was a painting depicting a modern, gender-fluid Adam and Eve, gazing at their smartphones before a backdrop of war and environmental degradation.

Rungjang said the inspiration for his piece, entitled Welcome to my World, ‘Tee’, was a transgender woman he knew in his youth – a person who, for him, defined feminine beauty, with her original gender status irrelevant. She committed suicide when he was still young, but her memory lived on with Rungjang as he came of age, a gay youth in a place that had little understanding, and often little tolerance, of what that meant.

“I loved her so much,” he said, “and then I was confused, because we didn’t have any kind of right education [on LGBTQ rights], as [we] were maybe being conducted by this society based on heterosexual kind of ways.”

“‘Son, I have no clue what this art is about, but the fact that you’re doing it in a public museum, that you seem to have so much support, you must be doing something right’”

Patrick Sun, founder of Sunpride Foundation, quoting his elderly father

The conventional view of Thailand typically includes a nod to “ladyboys”, and others who either defy the gender binary or make a life away from the norms of biological sex. It’s an image the country has incorporated into its tourism marketing, with ad campaigns and local hospitality geared toward attracting queer, foreign tourists looking for a tropical destination suiting their tastes and lifestyle, safe from bigotry and violence.

But for LGBTQ people in Thailand, the reality of life is more complex.

Kath Khangpiboon is a transgender rights activist and lecturer at Thammasat University in Bangkok.

“People have a lot of myths, and people think that Thailand is a haven for LGBT people, that it’s safe for them,” Kath said. “But in reality, in my personal experience as a transgender living in Thailand, it’s not true.”

That experience includes a lengthy court battle just to begin her job.

She was hired at her alma mater to teach on gender issues in the university’s social administration department, but was terminated before her first class for an alleged personal conduct violation, a charge that included a picture on her Instagram account of a penis-shaped tube of lipstick.

Kath, herself transgender, filed a discrimination complaint against the university and, after an extended legal battle, won her case and was reappointed as a lecturer. She’s now teaching classes two days a week at the university’s Bangkok campus.

Her experience shaped her efforts as an activist. Kath says that claims of Thai cultural acceptance for queer people are undermined by a legal system that offers tepid or incomplete protections for those whose gender identity is different from their officially documented sex.

The country does have a legal framework for preventing discrimination that could be invoked in cases like Kath’s. In 2015, the year after the country’s most recent military coup, the Thai parliament approved the Gender Equality Act and opened a lane for legal challenges to employment issues based on gender identity. The somewhat-progressive act defined gender to include “persons whose expression differs from the sex by birth”.

However, as Kath and other activists are quick to point out, the mechanism for filing complaints is opaque. Despite many anecdotal reports of discrimination, as of October 2018, only six cases had been settled for transgender people before the Committee on Consideration of Unfair Gender Discrimination, a deliberative body formed by the 2015 law.

While the landmark act does offer new protections, transgender people say the legal system generally fails to reflect the reality of their situation. Even their government-issued identification strictly records their birth gender, not the one they actually live as, which complicates the process of gaining social services.

“It is a big problem when you’re a trans person and you need to connect with the government, but your ID still says ‘mister’,” Kath said.

The Thai government, while ostensibly under civilian rule since Prayut Chan-ocha’s March election victory, is backed by the military and maintains an annual draft for its armed forces. This calls upon all men to be eligible for service, a group that, until 2011, was interpreted in Thailand to include transgender women.

That requirement was loosened in the years since by regulatory clarification, but men and women who are transgender are still caught in an awkward gray area when it comes to military recruitment, leaving commanders seemingly unclear about where and how such people may serve.

That’s just one area of dissonance between actual life and the letter of Thai law, which, up until this year, has been written entirely from the heteronormative perspective. But March’s election, the first democratic contest since the 2014 military takeover, saw the debuts of the country’s first open-and-out LGBTQ politicians.

That blossoming even included a shot at the prime minister’s office from Pauline Ngarmprine, a transgender representative who ran as a member of the Mahachon Party but later defected to Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit’s upstart anti-conscription, pro-democracy Future Forward Party.

While Ngarmprine was never considered a major contender capable of unseating military-backed PM Prayuth Chan-ocha, she was but one of a class of openly transgender political hopefuls – four of whom now hold parliamentary seats.

Tanwarin Sukkhapisit is of this freshman class, a thirty-something filmmaker who made her name as a director before transitioning to parliamentary life. Though she wasn’t in the Spectrosynthesis II exhibition, she visited the BACC to speak at a panel discussion with other artists about LGBTQ films in Thailand.

Tanwarin sets her views on queer rights within a wider context of democratic equality. She said her entry to politics was inspired by a legal fight of her own – a years-long campaign to release her 2010 feature film Insects in the Backyard after it ran afoul of Thailand’s morality law for including a snippet of pornography in the background of a scene.

The film was eventually allowed to be screened when the three-second clip was cut from the reel. But for Tanwarin, the message had already been received, and now she says freedom of expression is the centerpiece of her agenda in parliament.

Though she says LGBTQ rights are, for her, an indistinguishable component of human rights, she acknowledges that it was important for her to specifically represent people within that community.

“I wanted to be a symbol,” Tanwarin said of her political foray. “In the past [government leaders] would talk about us – but now we can talk for ourselves.”

That representation could advance LGBTQ rights in a few areas, both cultural and concrete.

Tanwarin said she chafes at popular media portrayals of people like herself, who often stand in as comedic foils for heterosexual actors. She notes in the other times LGBTQ stories are shown in the mainstream media, they’re often coded with the tragedy of family tensions, painful coming-out stories or lives of marginalised desperation.

That doesn’t leave much space for the other sides of queer life, particularly the well-adjusted people who are making lives in Thailand much like everybody else.

This normalcy was on display at the BACC through the work of the Spectrosynthesis II contributors. On a sunny Saturday, people of all ages, genders and orientations picked their way through the exhibit, their light chatter permeating the lofty rooms of the gallery space.

Patrick Sun, the founder and head of the advocacy group bearing his name, said this is largely the point of Sunpride’s work.

“We’re bringing gay people out into the open,” he said.

Sun, a businessman who started collecting gay Asian art about five years ago, provided many of the pieces on display at the BACC exhibition. He says the focus on art allows his organisation to home in on the universal themes of the LGBTQ experience – such as love, mortality and rebirth. But aside from the artistic values, he believes there’s a practical impact just from hosting public events for gay people in Asia, where subjects like homosexuality are the “elephant in the room”.

Sun highlighted this with an anecdote about bringing his elderly father to a Sunpride exhibition in Taiwan. After the then-99-year-old man was wheeled through the gallery space, the younger Sun asked if he’d understood what the works had meant.

“He said, ‘Son, I have no clue what this art is about,’” Sun recalled, “‘but the fact that you’re doing it in a public museum, that you seem to have so much support, you must be doing something right.’”

Sun, pausing to consider his point, continued: “So maybe not everyone will come to the museum and understand what the artists are talking about, what they’re trying to say. But they can feel this is a good thing here.”

Many of the attendees at the exhibition likely understood what the artists were saying.

Many of the attendees likely knew exactly what the artists were saying.

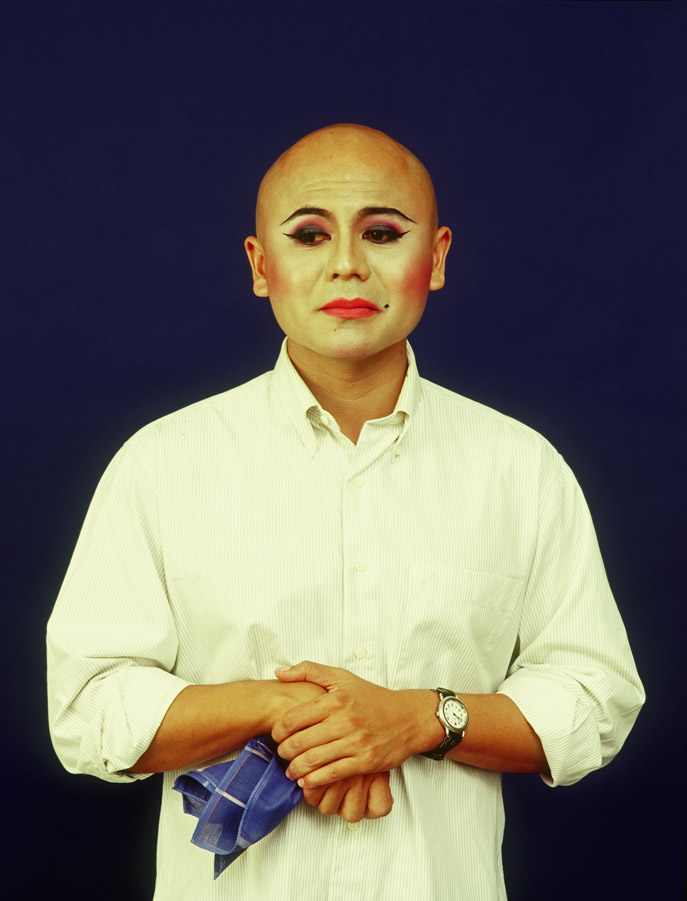

A pair of slender young men were two of many to stop before a photo from Thai artist Michael Shaowanasai. Their hands lightly clasped, they stood in front of a portrait depicting a man dressed in Buddhist robes and thick makeup in a style more commonly seen in a nightclub than a monastery, his eyes and lips touched in bright hues.

Exhibit curator Chatvichai Promadhattavedi, a life-long resident of Bangkok, is no stranger to gay art, nor local LGBTQ lifestyles. He was at ease in his gallery and didn’t believe the exhibition as a whole would be controversial to local viewers. Still, he allowed the Shoaowanasai piece – which had been the subject of past controversy for its subversive use of religious imagery in heavily Buddhist Thailand – could be the likeliest magnet for dissent.

“We don’t know what we’ll get, quite frankly,” he mused. “We might get a protest.”

Much of the work on display had a similar artistic relationship with traditional forms, including one of the first pieces to greet visitors at the exhibit entrance. Titled Der Nang Der, it is based on the “ling dao” puppetry found in the country’s northern Isan region.

With a suspended hodge-podge of small dolls, each connected to a mate by a glowing tube of green and pink neon, this puppet show might be slightly different than the ones found in the countryside. Many of the figures have prominent genitals – nearly half the size of their bodies – which bulge into space or suggestively link to to others.

For Chatvichai, the piece has a logical place here.

“If you take Thailand, it’s traditionally much more relaxed,” he explains, “So folk art and tradition is actually a good ally to this contemporary art.”

The historic familiarity with gender fluidity is still apparent in Thai culture, but the current political situation might dampen the links between past and present.

Besides her interest in free expression, politician Tanwarin is also working to introduce gender-neutral language into law to automatically extend legal inclusion to Thais with non-binary or transgender identities. She’s also opposed to Thailand’s recent tentative moves toward legalising same-sex unions – a move regarded in some circles as a progressive step – on the grounds that the legally separate category artificially separates these couples from their heterosexual peers.

And while equality under the law is a key point for both Tanwarin and Kath both women maintain the struggle of queer people is directly tied to broader fight for democracy under military rule.

“We want human rights, not LGBTQ rights,” Tanwarin said. “The power here is not with the people, but with the soldiers. That’s why we need to fight for the equality of the people.”

The Sunpride Foundation funded the Globe’s travel and expenses to cover the Spectrosynthesis II exhibition at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center.