On a humid night in August 2017, Myanmar government troops, aided by Buddhist militias, swept through Rohingya villages in Rakhine State, also known as Arakan, and opened fire on villagers. The army had launched what the government has called “counter-terrorist operations” in response to an attack on border police posts by Rohingya militants.

Their targets were members of the state’s Rohingya Muslim minority, a people denied citizenship in their home country by a government – led by Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi – that continues to label them illegal Bengali immigrants. The ensuing violence has resulted in the forced displacement of more than 640,000 Rohingya as of December 2017, according to OCHA, the UN humanitarian affairs agency. It is the biggest exodus of refugees since the 1994 Rwandan genocide, and the UN has described the violence as “ethnic cleansing”.

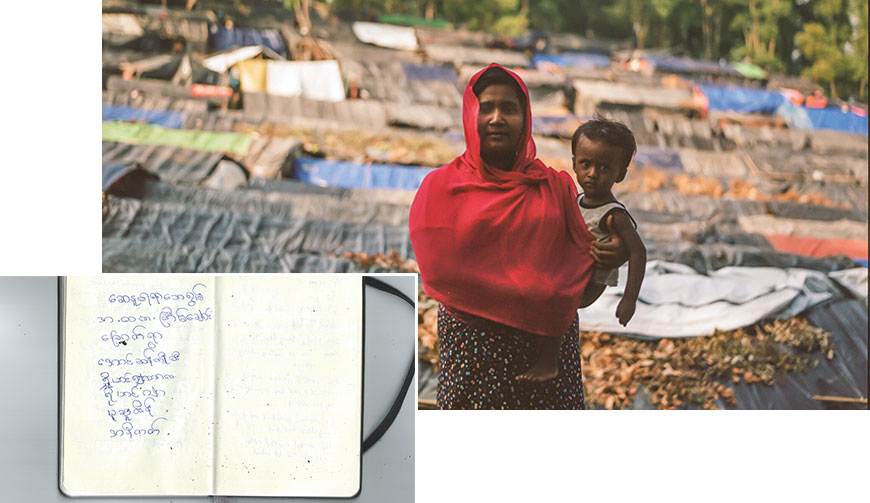

Currently, most of the displaced live in the muddied hills of Cox’s Bazar in neighbouring Bangladesh. Across the choppy waters of the Naf river, the natural boundary between Bangladesh and Myanmar, villages could previously be seen burning from fires set by the military and militias. All day and through the night, thick plumes of smoke bellowed up, mixing with the heavy monsoon clouds. Small fishing boats shaped liked crescents would glide in, packed with newly arrived and exhausted Rohingya, many of whom had trekked for days to reach the overcrowded camps. The shelters here are made out of bamboo and dug into the hills by the Rohingya themselves.

The monsoon weather brings with it the risk of waterborne diseases, and there is inadequate medical treatment to help with the scale of psychological trauma from witnessing and being victims of the violence perpetrated by the Myanmar military. Many of the accounts of the people Southeast Asia Globe spoke to corresponded with testimonies in interviews conducted by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, which have documented village attacks, mass shootings and rapes. In this portrait series, some of the Rohingya living in camps along the Myanmar border recount their ordeal and voice their anger at the Myanmar government and the international community in handwritten letters.

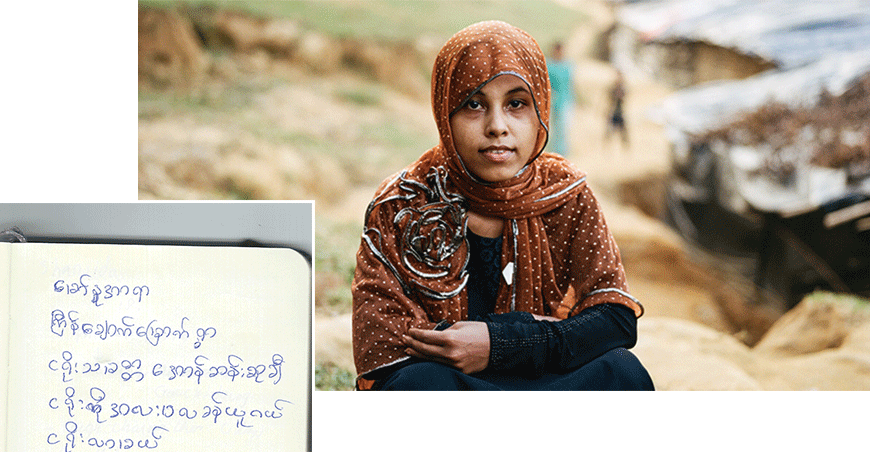

Mohammed Shofi, 20, from Buthidaung

The military raided Mohammed’s village and doused petrol over houses. Women were taken into a large house, and they started to scream. Outside, men were lined up and shot. Those who survived the initial shootings were executed by the Buddhist militia. Afterwards, the house, which contained a few hundred women from the village, according to Mohammed’s estimates, was shot into and then set on fire. Mohammed crossed the border into Bangladesh via the Tombru border post.

Army came to my village and started to round up and shoot many men and women. I want the world to call for justice for what happened and for action to be taken for the people who died.”

Munwara Begum, 20, from Boli-Bazar

On 24 August, the army and Buddhist militias came to Munwara’s village. She saw bullets raining down throughout the night outside in the jungle, and the next day she saw a helicopter dropping soldiers down by rope to the fields outside her village. Her uncle was shot by one of the soldiers, and they then raided the houses next to hers. While they went through the houses across her street, she fled with her son and husband.

I am Munwara Begum from Boli- Bazar, Myanmar. I fled on August 25 to Bangladesh fearing for my life and came with my young children.”

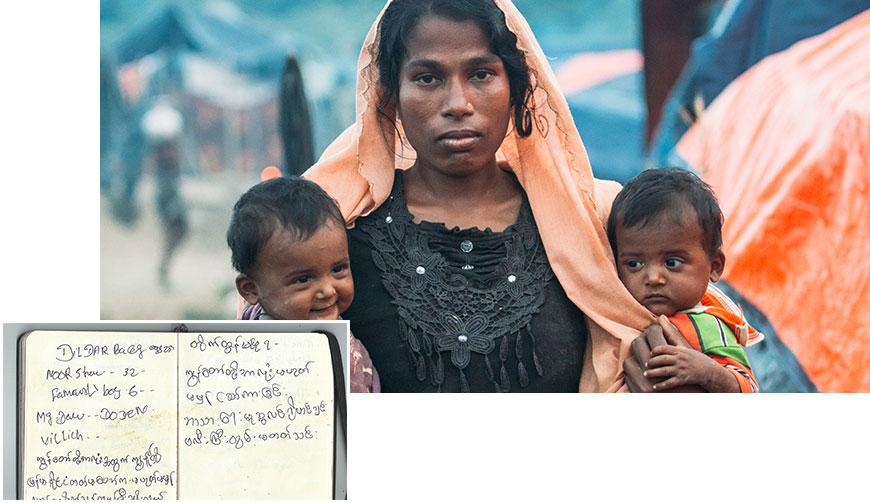

Noor, 32, from Maungdaw

Noor is a mother of six-month-old twins. Her husband, Dildar, worked as a shopkeeper in their village in Maungdaw. Typically, women in Rohingya villages in rural areas do not attend school for many years. Her husband wrote her message.

We are citizens of Burma. Aung San Suu Kyi can save our citizenships and keep us in our land, but she gave power to the army chief Min Aung Hlaing, and in doing so gave him the power to kill us. When the military find us in the open, they shoot at us. Old people, children, women, everyone gets hit by the bullets… They raped the women. They burnt our villages to the ground. The villages are gone. We are Rohingya; our home is Arakan [Rakhine]. We will only go back if they [the government] can accept us as Rohingya.”

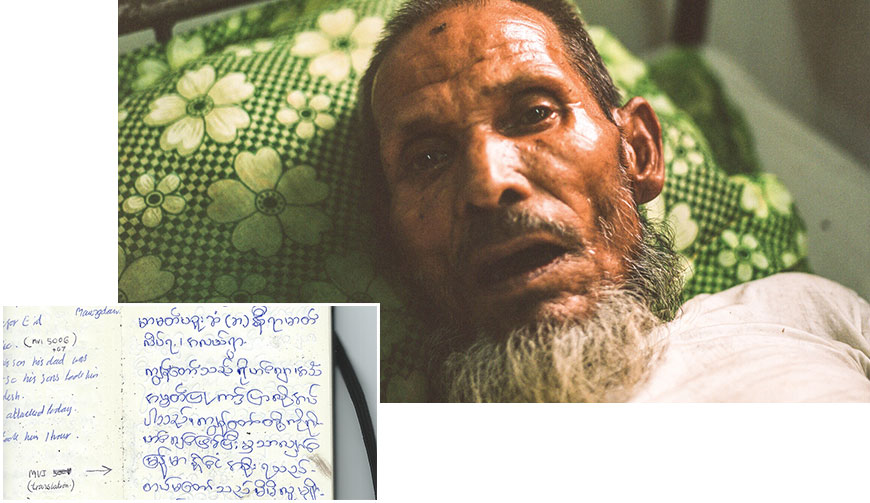

Nur Mohammed, 75, from Maungdaw

Nur worked as a fisherman in his village. When the army launched attacks there on 30 August, he was fishing. As bullets flew over his head from the nearby houses he ran for his life and then saw a helicopter hovering above him. It circled around the village before flying directly over him. He saw grenades being tossed out of it, and one of the grenades ripped apart the sides of his legs. His wife managed to escape but fractured one of her hands.

A while back, the government gave us assurance that they will give us citizenship rights, but they lied. We demanded that citizenship rights should be granted to our Rohingya identity, but they denied it and they tortured us cruelly. We cannot have our Rohingya identity in Myanmar, but others outside accept us as Rohingya. Myanmar has always been our home. And now as we ask for the right to our identity again, the government launches attacks on us. They burn our villages, they force us to leave our land – even Aung San Suu Kyi does not accept us.”

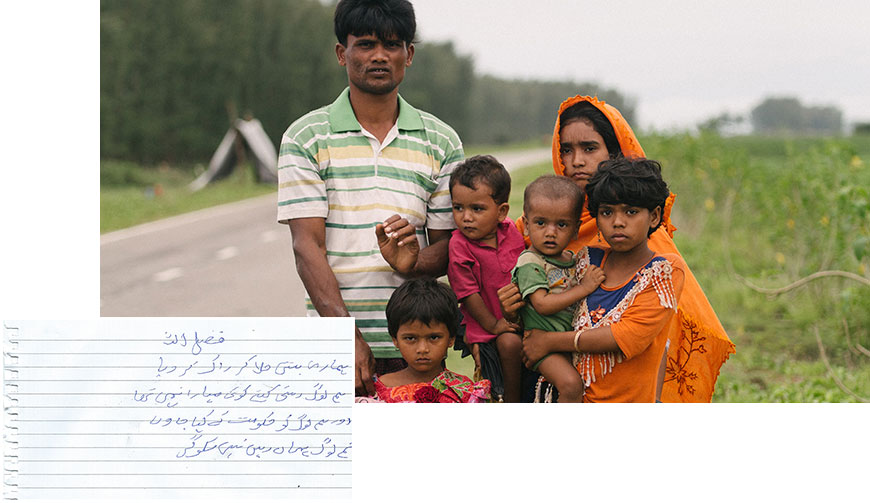

Mohammed, 36, from Rathedaung

Mohammed fled with his family after the army started burning homes and shops in their village. The journey, which largely involved fighting through dense jungle and wading through thick mud across paddy fields, took them four days. They carried all their belongings as they fled with their children aged eight, three, two and one. They estimate that about 200 people in their village were killed, including Mohammed’s father who had his stomach slashed open by the Buddhist militia.

The military burnt my house down and then told me that Myanmar is not my country. They told me to get out of their land, but I don’t know anywhere else that is home. Now my family and I don’t know where else we can go.”

Nesaru, 38, from Maungdaw

Nesaru’s village was attacked on 1 September on the day of Eid. She saw men from her village having their throats slit by the Buddhist militias. Her nephew was one of those killed during the attack, as well as her son-in-law. She used to take care of the animals on her farm before the atrocities and was forced to leave them all behind as she escaped to Bangladesh where she lives in the Kutapalong refugee camp.

I never want to go back. Aung San Suu Kyi promised we would be safe the last time the violence broke out, and she failed to stop it. I never want to go back.”

Sanwara Begum, 26, from Boli-Bazar

Sanwara fled her village with her two sons: Mohammed Yusuf, aged one (pictured), and Saiful Islam, aged ten. Her husband followed them, and together they live in the Kutapalong refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar. Sanwara used to be a shopkeeper, selling mobile phone credit and other goods, before the Buddhist militia and the army arrived in her village on 25 August, setting up military outposts on the perimeter of their village and often beating people in the markets.

I am Sanwara Begum from Boli-Bazar, Myanmar. I have two children and a husband and fled from the Mogh [Buddhist militias] who came to our villages and started shooting.”