The CIA arrived in Moung Cha, an untamed area of forest on the slopes of Phou Bia, the highest mountain in Laos, looking for somewhere secluded from where they could wage a secret war. It was the early 1960s and, as the conflict in Vietnam was escalating, there was growing concern that a communist uprising might also take place in Laos.

An intermittent civil war had begun in 1954 between the US-backed Royal Lao government and the communist Pathet Lao; a battle that alternated between political and armed struggle.

In order to curb the Pathet Lao and to stop the flow of North Vietnamese supplies along the so-called Ho Chi Minh Trail in eastern Laos, between 1964 and 1973, US planes dropped more than two million tonnes of bombs on the landlocked country during almost 580,000 raids, according to Martin Stuart-Fox, emeritus professor of history at the University of Queensland and author of numerous books on Laos. This equates to almost one planeload of bombs every eight minutes for nine years.

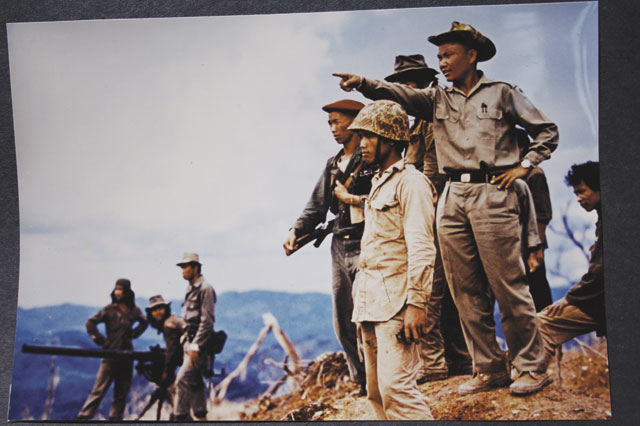

But it was not only bombs that the US used to combat the Pathet Lao and its Viet Cong allies. Unlike in Vietnam, the US did not send ground troops into Laos – this was a ‘secret war’ that violated international agreements. Instead the CIA carried it out with the support of the Hmong people, a hill-dwelling ethnic minority of whom many had been fighting on the side of the Royal Lao government since the beginning of the conflict.

“While many Lao people and other upland groups also fought in this secret army, the Hmong were arguably the most important group of fighters,” explained Ian Baird, an assistant professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and expert on Lao political history. “Approximately two-thirds of Hmong people were involved in the ‘secret war’ on the side of the royalist government.”

In Moung Cha, the CIA established a secret military base at Long Cheng. There, under the command of Vang Pao, a major general in the Royal Lao Army and de facto leader of the Hmong guerrillas, the ‘secret war’ was fought against Lao and Vietnamese communist forces.

According to Stuart-Fox, the Hmong were motivated to fight by a combination of factors. “They feared domination by the communist Pathet Lao, and thus the Vietnamese, and feared they would lose the autonomy they enjoyed within their mountain villages – both of these were emphasised by American operatives,” he said. “They were also paid and fed by the CIA in return for agreeing to fight for them.”

After years of bitter fighting, the conflict came to an end in February 1973 when a peace agreement was brokered between the Pathet Lao and the Royalists. A coalition government was established and the CIA began withdrawing from the country. However, the Pathet Lao began to gradually violate the peace agreement and overthrew the royalists from the government two years later.

While Vang Pao and a number of his officers and their families were airlifted by the US to Thailand, tens of thousands of Hmong soldiers and their dependants were left behind. Some were able to sneak into Thailand and large numbers eventually made it to the US and France while others kept on fighting, although a significant number were killed.

“When the Americans left Laos, the Vietnamese and Lao armies tried to control the country and accused us of having worked for the CIA,” remembered Soua Cheng Her, who was a leader of the Hmong resistance in the Vang Vieng area. “‘You collaborated with CIA, now you are CIA,’ they used to say”.

Like many Hmong fighters, Cheng Her remained in the mountains in fear of his life. “We had to shelter and hide,” he explained.

For almost three decades after the war, he commanded a group of 400 families that hid in the jungles. “We didn’t have anything, no weapons, and little food and clothes.” During that time, Cheng Her’s families ate yams, fruits, bamboo shoots and hunted small animals. Occasionally, they obtained rice from villagers who supported them secretly. “We had to move constantly – every few days. The Lao Army used planes and heavy weapons, so if we stayed for too long, they’d kill us,” said Cheng Her.

“The Pathet Lao promised reconciliation, but the Hmong who had fought for the Royal Lao government feared retribution – if not mass murder along the lines of the Khmer Rouge, then incarceration in re-education camps,” explained Stuart-Fox. “So many of those who stayed feared surrendering and fought on. The Pathet Lao in turn feared that continuing Hmong insurgency would increase anti-communist support, so they were determined to suppress it.”

Of those who fled Laos, a significant number established groups opposed to the new communist government from their bases in the US and France. “The Hmong and Lao overseas got organised; the largest resistance group was led by Vang Pao, called the United Lao National Liberation Front, or Neo Hom,” explained Baird. The Neo Hom channelled money and arms to exiles in Thailand, who then smuggled them into Laos.

However, in 2007 Vang Pao was arrested in the US for allegedly plotting to overthrow the Lao government and of smuggling weapons into Thailand – a violation of the US’ Neutrality Act – even though the US government had turned a blind eye to resistance organisations for many years prior to the arrest. The charges were later dropped and Vang Pao died four years later. According to Baird, in recent years many of the opposition groups overseas have dropped their explicit aims of overthrowing the Lao government and have focused on shedding light on human rights violations in Laos.

Today, only one armed resistance group remains in Laos: the Chao Fa. Inspired by a Hmong religious leader who was assassinated in Laos in 1971, a hundred or so Chao Fa soldiers continue their armed struggle against the government in the Moung Cha area. Many are starving, under-equipped and exhausted. Most are the children or grandchildren of the Hmong soldiers who fought during the ‘secret war’.

“We need help; a lot of Chao Fa children and old people are dying,” explained Chong Lor Her, president of Chao Fa.

An attempt was made to reach Moung Cha to interview Chong Lor in person, however, Lao authorities had placed a ban on all foreigners travelling there. When Southeast Asia Globe’s contact later visited the area, he was ambushed and two people in his convoy were killed. Chong Lor was, however, available to speak via satellite phone.

“The Lao government coordinates its military in all regions, from the south to the north, in an attempt to come and kill us,” he said. “They also use Vietnamese soldiers. Last November, they ambushed my people north of Moung Cha and now they continue attacking the region. They also use airplanes to fly over our region and spray chemical agents to kill us.”

It is not known how many Hmong have died in combat since the 1950s, although according to the Congress of World Hmong People, an organisation based in the US with links to the Chao Fa, at least 200,000 Hmong people have perished – this figure is, however, contentious.

Many have given up the fight. Cheng Her is one of them. “There wasn’t any other choice. We didn’t have weapons for protection, food, medicines or clothes,” he said while sat in a small hotel room in Thailand that he fled to several months ago following an attack on his guerrilla unit, in which several fighters were killed.

Chong Lor said he understands why people made the decision to stop fighting. However, he insisted that the Chao Fa fighters who are still standing will continue their struggle.

Unlike other resistance movements, such as the Neo Hom, the Chao Fa does not fight in order to remove the communists from power and restore the exiled Royal government.

“We cannot live in the Lao nation any more,” explained Chong Lor. “We are defending our Hmong freedom. Our claim is that peace must come from the international community recognising [the Hmong] as a nation of people. We feel no betrayal by the CIA, it was a good cause and a golden opportunity for the Hmong to unite and exercise self-determination.”

However, while Chong Lor and the hundred or so remaining Chao Fa fighters call for an autonomous Hmong nation, a significant number of Hmong people who remained in Laos after the conflict learned to adapt to the new government.

According to Baird, it is important to remember that as many as a third of all Hmong combatants fought on the side of the communist Pathet Lao during the civil war. “For these, there have been rewards. Some of them are now senior members of the government,” he said.

In 2011, Pany Yathotou, the daughter of one of the Hmong communist leaders, became both the first female and the first Hmong person to be appointed as president of the Lao National Assembly.

Stuart-Fox added that while many Hmong continue to suffer in modern-day Laos – they are regularly forced off their land to make way for foreign mining, damming or agricultural companies – and still face discrimination in the area of religious rights, these are problems shared by other ethnic groups in Laos too.

“Hmong tend to be hard-working and entrepreneurial, and some have definitely thrived,” he said. “There is a relatively large Hmong population in Vientiane and, in general, they are not discriminated against any more than are other minorities.”

As Laos undergoes big economic and social changes, a number of Hmong people, often the younger generation born abroad, are beginning to return to Laos.

Daniel Vang is one such returnee. In 1975, his parents fled the country just before the Pathet Lao came to power and were fortunate enough to eventually make it to the US, where they set up home in California. Now, 40 years later, their youngest son is living in their homeland and said that he was just one of many.

“I know quite a few people like me, children of migrants, who have returned,” Vang explained. “At first, I was interested in visiting Laos to know more about my roots. That was about ten years ago, and on my third visit I decided to stay.”

According to Vang, 28, his parents were initially unhappy with the decision but understood his reasons.

“I didn’t do too well at school and back in the States the only work I could find was in a factory for six bucks an hour. But over here, I’m considered middle class,” he said.

Like many of his fellow returnees, Laos’ economic boom has been a significant factor in the decision. For the past decade, the economy has enjoyed average annual growth of 8%, while GDP increased from $2.7 billion in 2005 to $11.1 billion in 2013, according to the World Bank.

Vang has now been in Laos for three years and has become something of an entrepreneur, running two successful mobile phone shops in the capital, Vientiane. When asked about his Hmong heritage, he was hesitant.

“Maybe if I was a poor farmer in the countryside I’d be treated differently,” he said. “But here [in Vientiane] I don’t think anybody cares and I’ve never had problems. I think the times have changed.”