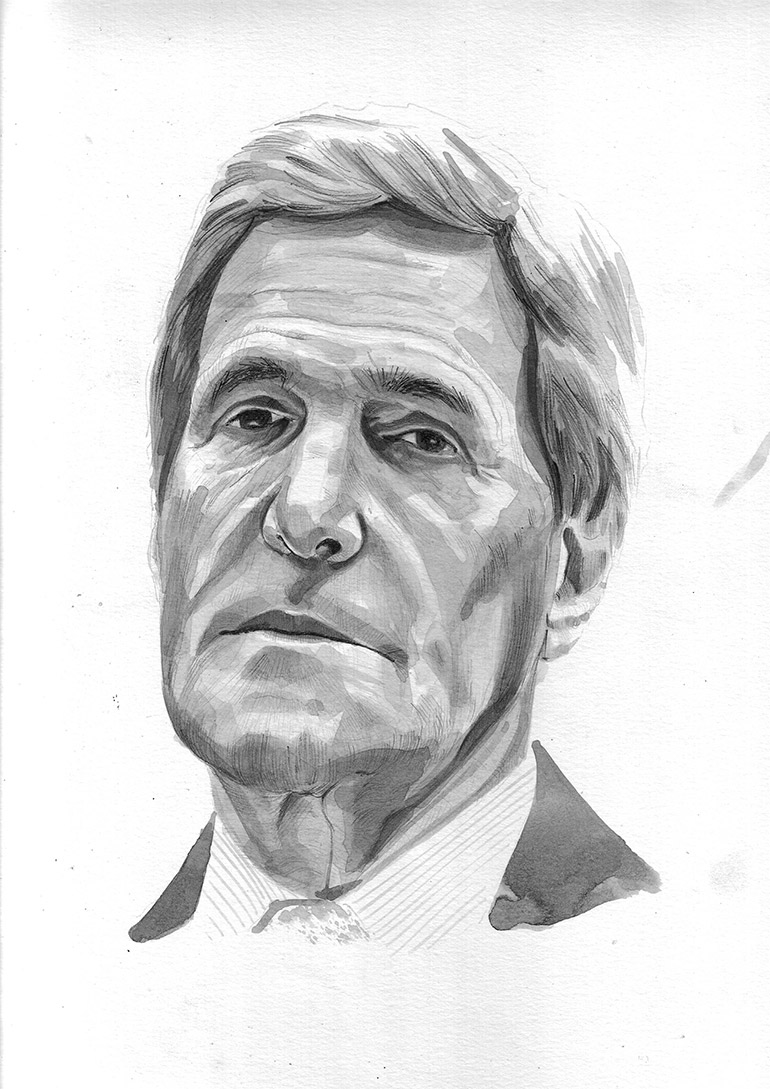

As US secretary of state John Kerry enters his final months in office, what has the Vietnam veteran achieved in Southeast Asia after almost four years of diplomacy?

If he had been ferried around the world on private carriers rather than US government jets, secretary of state John Kerry could have clocked up an impressive amount of loyalty air miles between taking office in 2013 and his scheduled departure from the job in January. At the time of writing, he had racked up 1.23m miles in-flight, meaning he has spent about 112 days on aircraft while in the job.

During this time, Southeast Asia has been no stranger to Kerry’s avuncular presence and jutting jawline. He has made no fewer than 18 trips to countries in the region, with every Asean country bar Thailand rolling out the red carpet for him. Vietnam and Indonesia have welcomed him three times, and Laos twice.

Kerry is a busy man for good reason, as he told the Aspen Ideas Festival in late June: “The United States of America is more engaged in more places with greater impact today than at any time in American history. And that is simply documentable and undeniable.”

While Southeast Asia is definitely on the US strategic radar, there is no doubt that Kerry has had more pressing issues to attend to on his watch, such as conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine. “There’s a limit to how much time an individual can spend on one region, especially someone as busy as the secretary of state, and in the US list of priorities and interests, Southeast Asia figures relatively low,” said Donald Greenlees, a researcher at the Australian National University’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre.

According to Brendan Thomas-Noone, a research associate at the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, the secretary of state’s focus in the region has mostly been on keeping “the boat balanced” by providing continuity from the legacy of his predecessor, Hillary Clinton, and the Obama administration’s strategic ‘Pivot to Asia’. Crucially, though, Thomas-Noone believes Kerry has never succeeded in making these initiatives his own.

“But he has largely kept up US interests in the region and pushed the US rebalance, mainly through the TPP [Trans-Pacific Partnership], one of his successes in the region,” Thomas-Noone said.

Indeed, the TPP, a free trade deal between the US and 11 Pacific Rim nations including Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia and Vietnam, is America’s most visible initiative in terms of countering the might of its biggest rival, China. Everything about the relationship between the US and Southeast Asian nations can be viewed through the prism of China, according to Greenlees. He believes that as Beijing has become more assertive, particularly in the South China Sea, some countries in the region, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, have edged increasingly towards Washington.

“I think a number of countries have quietly moved closer to the US and done more to bolster the military and diplomatic aspects of the relationship,” Greenlees said. “And there’s been a willingness to look at deeper economic ties with the US.”

Although Kerry may not leave an immediately tangible legacy in the region, his success in bringing Vietnam closer to the US is not insignificant. A veteran of the Vietnam War himself, his admission in August 2015 that the conflict “stemmed from the most profound failure of diplomatic insight and political vision” came ahead of only the third visit by a sitting US president to Vietnam since the end of hostilities. That visit was notable for Obama’s announcement that the US would lift a ban on arms sales to Vietnam.

However, Kerry has been unable to shepherd Asean into presenting a united front against China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, and it is this issue that will loom large for his replacement as 2017 dawns. And with no end in sight for military rule in Thailand, it might be time for a rethink of the relationship between Bangkok and Washington.

“[His successor] will have to deal with continued uncertainty in Thailand,” said Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. This was a situation, he added, that may precipitate “a need to move some of the US government agencies with regional headquarters in Thailand” out of the Kingdom.