What happens when children begin to realise that their parents are following a different path? What happens when that path ends behind bars? Or on the receiving end of a bullet? What happens in the minds of children whose parents are terrorists?

Khairul Ghazali had plenty of time to think about these questions when he was in prison – six years, exactly, the shortest sentence among his comrades convicted for terrorist activities in 2010. He had plenty of time to think not just about the children killed in the bombings carried out by the terrorism organisation he was a part of, but also those whose parents were sitting in cells near his.

He thought not about changing the roots of terrorist organisations in Indonesia but changing the seeds, so to speak. He thought about digging up those susceptible to perpetuating Islamic militancy and re-planting them in a new, healthier plot of land.

This ultimately ended up being 30 hectares near Medan, the capital of North Sumatra, now the site of Ghazali’s Al-Hidayah Islamic Boarding School.

Ghazali was born into a family that was part of Darul Islam, an Islamic group founded by militias that fiercely believed in turning Indonesia into an Islamic state. As a teenager, in 1984, he joined Indonesia’s Jemaah Islamiyah, a separatist terrorist organisation borne from Darul Islam. As a young adult, Ghazali helped carry out bombings and bank heists around the country before being jailed in 2010.

When officials from Indonesia’s National Agency for Counter-Terrorism (BNPT) visited the prison where he was being held, Ghazali shared with them his vision to stunt the future of Indonesian terrorism through education, to give children whose parents have been involved in terrorist activities an emotionally safe place to learn, a place where they weren’t exposed to violence. The school would be an embodiment of the shift in his definition of jihad.

“This school is to prevent radicalism from touching the children of terrorist families”

By the time he went on parole in 2015, word of his idea had spread among national and local government, and the governor of North Sumatra sent a plea to the Minister of State-Owned Enterprises on Ghazali’s behalf to grant him the land. With the help of friends and family, he realised his vision and built Al-Hidayah.

With round cheeks sandwiched between a tuft of beard and thick-rimmed glasses, Ghazali brims with joviality, his wrinkle-free 52-year-old skin hiding the turmoil of his past. “This school is to prevent radicalism from touching the children of terrorist families,” he says. “I chose a place somewhat away from the crowd or in the suburbs in order to have the land and soil for children to learn life skills.”

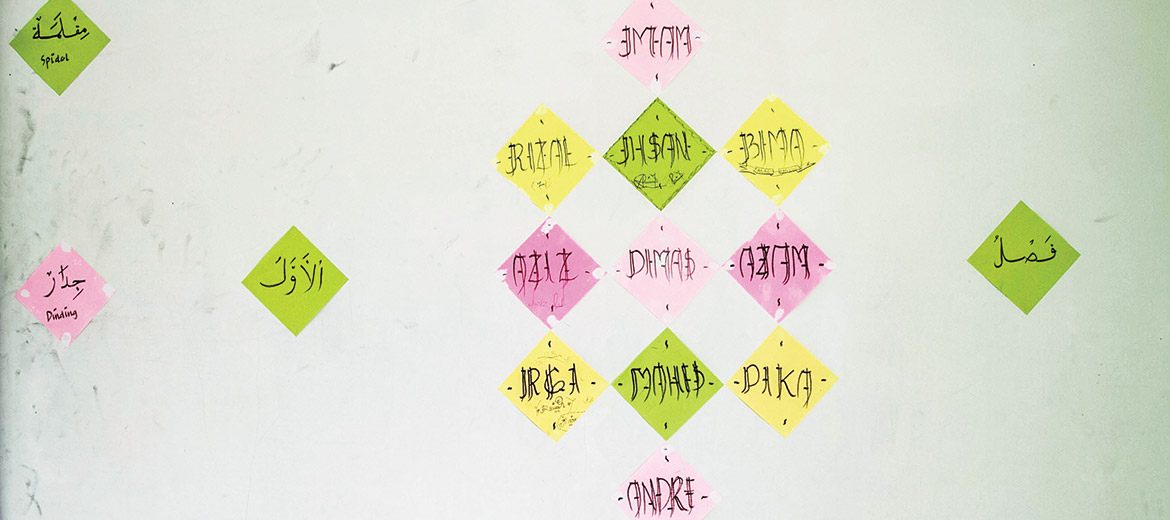

The 20 male students currently enrolled live on campus and learn the standardised Indonesian school curriculum supplemented with lessons in English, Arabic, entrepreneurship, agriculture and psychology. Some have fathers behind bars; others have witnessed their father’s death. But this is not a rescue mission, and although Ghazali visits the homes of the students, they must come with the consent of their parents or guardian. The school’s religious ethos follows rahmatan lil ‘alamin, teaching Islam through a lens of peace and tolerance. On one occasion a student was withdrawn when his parents returned to radicalised beliefs.

Al-Hidayah’s key goal, however, is to surround students with others who come from similar homes, who see each other as normal, who are taught why and how to step off the path they might have unknowingly been on and support one another along the way.

“Being different from other children is not easy, and these students have to be counselled on how to cope with mockery from other kids, how to develop their self-esteem, how to think they are equal compared to other ‘normal’ children,” says Hamdi Muluk, a professor of psychology at the University of Indonesia who has researched and published extensively on the psychology of terrorism. “Children also might not understand what terrorism means. This can make them feel confused, not confident, fearful of being rejected. And if they feel frustrated, they might convert this to revenge or hate. This can become a serious problem when they reach their teenage years. Someone has to explain to them realistically what happened to their parents.”

While terrorist activities in Indonesia are currently few and far between, Ghazali was a prime contributor during a period when they were at an all-time high. When he joined Jemaah Islamiyah, Indonesia was under the administration of President Suharto, a military dictator who pursued the archipelagic country’s unity through the doctrine of Pancasila – a five-pillared ideology that promotes coexistence of multiple religions – over Sharia law. There was no tolerance in Suharto’s regime for radical Islam, and their desire to flee from this oppression pushed Ghazali and others into Malaysia and Thailand, often using time abroad to equip themselves with bomb-making and weaponry skills.

When the regime finally fell in 1998, Jemaah Islamiyah returned to Indonesia to carry out terrorist activities around the archipelago. The Bali bombings in 2002 and 2005 killed 202 and 20 people, respectively, the 2003 Jakarta bombing at the Marriott Hotel killed 20, the 2004 bombing of the Australian embassy killed nine and the 2000 bombing of the Philippine embassy killed two. There was also a 2010 bank heist in Medan in which an estimated $44,000 was stolen. Two days later, a midnight attack on the police headquarters in Hamparan Perak, North Sumatra, left three officers dead.

Following this final attack, and knowing they were being pursued by the Indonesian Special Forces’ counter-terrorism squad known as Densus 88, Ghazali took his comrades to his home in Tanjung Balai, about five hours east by car from the scene of the crime. Their hideout was quickly discovered and, a month later, Densus 88 raided Ghazali’s home, ending in the death of two terrorists and prison sentences for the rest.

The bedlam of Ghazali’s former life could not be in starker contrast to his current surroundings.

The school is a simple and peaceful place, comprising two classrooms with pastel lemon-and-lime-coloured walls, a mosque, a couple of offices, a workshop space, three outdoor play areas and dorms. Tuition is free, the eight teachers all work as volunteers and funding comes from Ghazali himself, as well as a cohort of high-ranking government officials who got behind the project: the head of BNPT, Suhardi Alius; National Police chief Tito Karnavian; and the police chief of Medan, Mardiaz Kusin.

Alius was one of the first government officials to become aware of the school, hearing about it from members of his staff who visited Ghazali in prison, and is now the school’s most active supporter. While such a place certainly aligns with the goals of BNPT, the school moved Alius on a personal level and he fundraised among his friends to help build the school’s mosque without touching government money.

“These children are victims,” Alius says. “They’re often ostracised and experience social punishment, and as they get marginalised and secluded they might get closer to their parents’ ideology. But here, they’re loved and given attention and put in society instead.” He’s made the trip from his base in Jakarta to visit the school three times, and BNPT now develops Al-Hidayah’s curriculum as part of its annual task list.

“There was stigma; we were considered to be producing child terrorists. We were reported to authorities who eventually came to see me and saw we were not printing future generations [of terrorists].”

Despite the uplifting nature of his idea, Ghazali has struggled to re-socialise himself and establish his school as part of the local community, which initially opposed the project on suspicion that its ethos was a sham and that Ghazali was using it as an undercover way to continue working for his former organisation.

“At first I was opposed by the community,” Ghazali says. “There was stigma; we were considered to be producing child terrorists. We were reported to authorities who eventually came to see me and saw we were not printing future generations [of terrorists].”

Despite such accusations, rejection is just as strident from the other side too. His former comrades now view him as a traitor – a puppet of the government and a doll of Densus 88 and the BNPT.

Soon, though, the brother of one of the Bali bombers will be establishing a similar school in the East Java village of Tenggulunan, which will also be supported by BNPT and the local government. Alius says there might even be a third school on the horizon.

Ghazali would never claim that Al-Hidayah is a perfect model but, for the students who stay, his new form of jihad seems to be working.

“I’ve studied here since August 2016,” says Ahmad Irgi, an 11-year-old student who had dropped out of public school after fifth grade. His father died in prison in 2015. “My mother brought me here to study religion and skills so that I can be a pious and able son. Now I have a lot of friends. And many of them have shared my same fate.”

And what, exactly, does Irgi hope his future holds? A career as a police officer.

Photography by: Albert Ivan Damanik