Editor’s note: Elephants have long been a symbol of might and majesty across Southeast Asia. Six years ago, Southeast Asia Globe travelled to the faded halls of Myanmar’s royal white elephants, kept in chains to prop up the collapsing junta’s so-called divine right to rule the nation. This World Elephant Day, we’re sharing their stories here.

Shaded by a gilded three-tiered pavilion, they rock from side to side, taking two steps forward, then two back, each futilely pulling against a short chain tethered to their right foreleg. “Weaving,” veteran Swiss elephant keeper Georges Frei writes, “is a surrogate activity caused by boredom, frustration and desolation.”

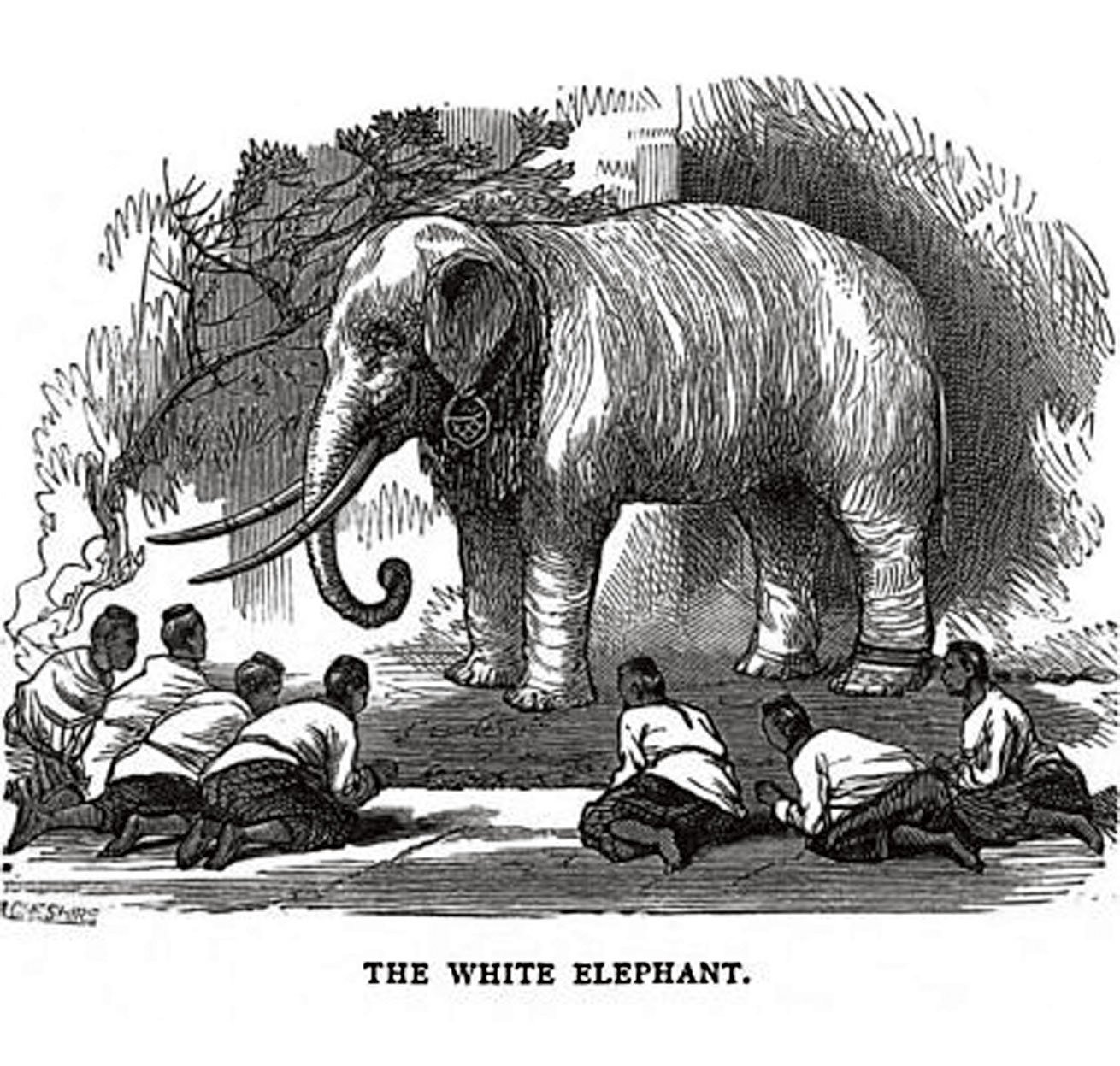

Occasionally, an elephant handler (known in Myanmar as an ‘oozie’) in a longyi and undershirt approaches the animals with pieces of sugarcane. The squat, dust-pink female on the far left has been trained to kneel and beg for her treats. There is a thick band of scar tissue on her left hind leg, perhaps from when she was ensnared in the remote jungles along the Myanmar-Bangladesh border. The other elephants – a large male tusker, slate-grey with irregular light splotches, and a young salmon-coloured female – are fed at trunk’s length.

“The white elephants are a sign of the good future awaiting our country,” U Ottama says. The elderly monk, who lives south of Yangon, comes to the Royal White Elephant Garden whenever he visits the city.

Ma Nu, 45, manages the viewing pavilion’s small concession stand. “I work here because my husband captured one of the elephants,” she says. For his efforts, the family was given $70 and a $90-per-month job selling snacks, soda, juice, water and Thailand’s Chang beer – twin white elephants basking under the limbs of a golden Bodhi tree on the perspiring green cans – to locals, and the Chinese and Thai bus tourists that visit the site.

Ma Nu lifts a plastic basket of cigarettes off her stand to show me silver rings, bracelets and amulets threaded with a thick strand of pale elephant hair. She claims that the charms, which start at $10, ward off evil spirits and help ease childbirth. Apparently, they are very popular with Thais.

“I don’t particularly like working here,” Ma Nu says, “but I believe in the power of the white elephants.”

When Ma Nu’s husband captured the mottled male in Rakhine state in 2001 – the first white elephant seen in the country in nearly four decades – state media proclaimed that the animal would bring the country “peace, stability and prosperity”. In a lavish ceremony, the eight-year-old bull was given the name Yaza Gaha Thiri Pissaya Gaza Yaza – or, ‘Royal Elephant that Bestows Grace Upon the Nation’.

For centuries, Southeast Asian monarchs have coveted white elephants as embodiments of a divinely sanctified rule. “Politically, socially and economically, they are signs of positive change,” fortune-teller Min Kyaw Khaung says from his cramped office near Yangon’s Maha Wizaya Pagoda.

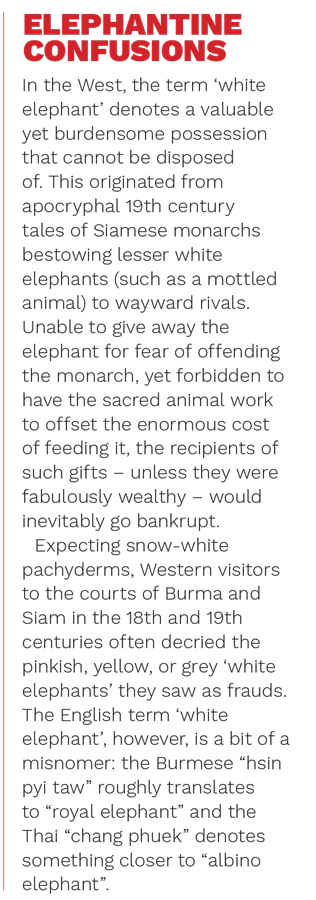

Expecting snow-white pachyderms, Western visitors to the courts of Burma and Siam in the 18th and 19th centuries often decried the pinkish, yellow, or grey ‘white elephants’ they saw as frauds. The English term ‘white elephant’, however, is a bit of a misnomer: the Burmese “hsin pyi taw” roughly translates to “royal elephant” and the Thai “chang phuek” denotes something closer to “albino elephant”.

Considered necessary adjuncts of royalty, wars have even been fought to obtain them. Burmese King Bayinnaung, for example, invaded Ayutthaya in 1563 to rob Siamese monarch Maha Chakkraphat of his pale pachyderms. In 1583, Venetian merchant Gaspero Balbi saw Bayinnaung’s bounty whilst visiting the present-day town of Bago: “When [the King] goeth to his recreations solemnly, or in his Robes, four white Elephants go before him vested with Gold, having their teeth inclosed in a sheath wrought with Jewels.”

Kings boasted of their possessions. The vanquished Maha Chakkraphat had styled himself ‘Lord of the White Elephant’. In 1820, Thai King Rama II celebrated his possession of three white elephants by adding one to his country’s flag. Burma’s King Sagaing Min confidentially referred to his royal self as ‘Lord of All White Elephants’, and for its part, the government of Myanmar released a 5,000-kyat note emblazoned with a white elephant in 2009.

White elephants represent the greatness of the king, queen or government that possess them.

Min Kyaw Khaung

If possessing a white elephant was a sign of good fortune, to lose one was to be doomed. Following the death of a young white elephant, 18th century missionary Vincentius Sangermano describes Burma’s king as being “overcome by the most abject fear, expecting every moment to be dethroned by his enemies, and imagining that there remained to him but a few days of life”. Thibaw Min, the last king of Burma, seems to have ignored such ancient misgivings. In 1885, he sanctioned the sale of a white elephant to American circus proprietor Phineas Taylor Barnum; less than two years later, Thibaw’s kingdom was conquered by the British and the monarch was exiled to India.

ALL THAT GLITTERS… AND GOLD

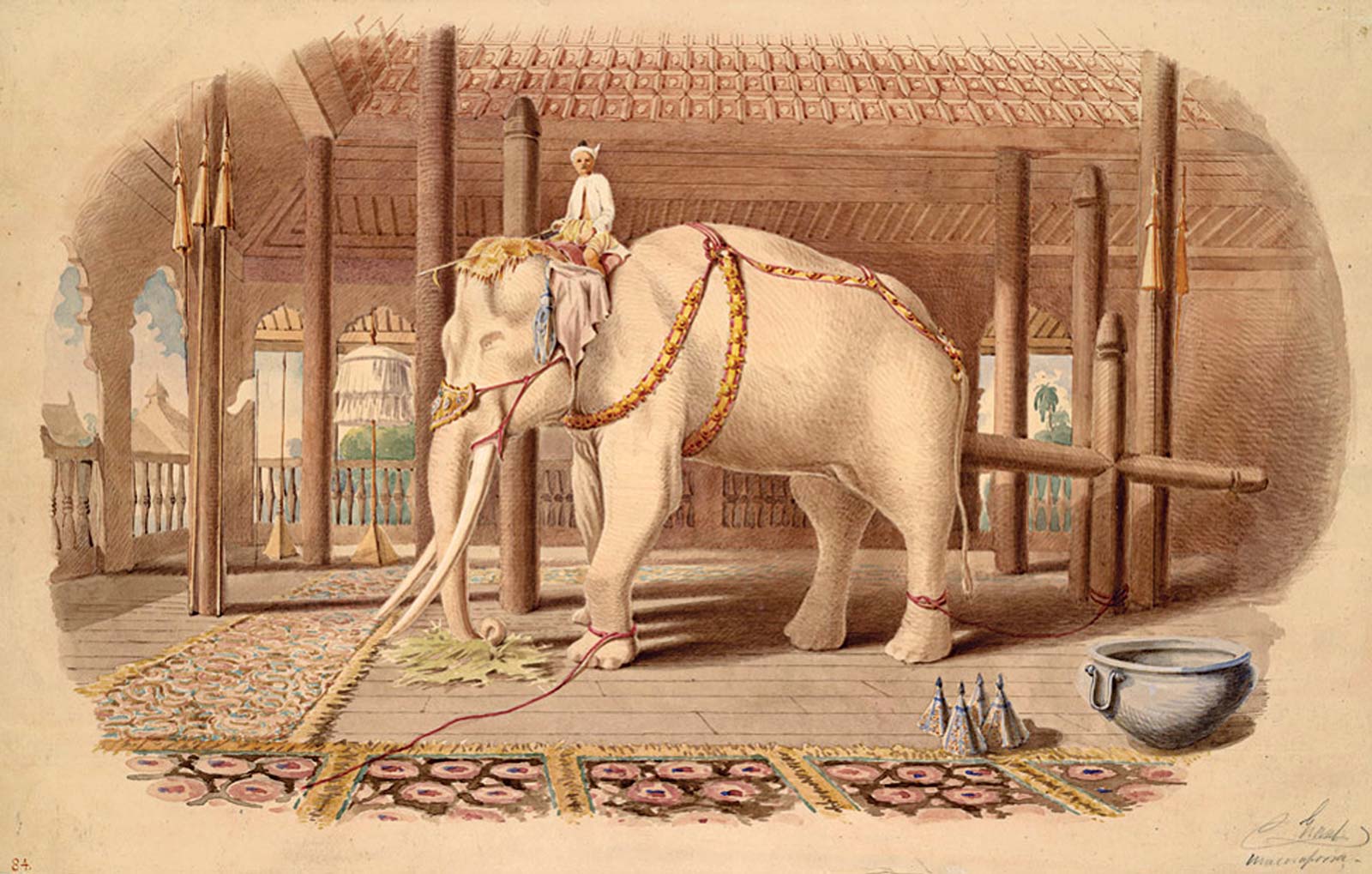

The extravagant ways in which Southeast Asian monarchs have doted on their white elephants has sometimes bordered on obscene. The following firsthand account of a Burmese white elephant comes from British journalist and colonial administrator James George Scott’s 1882 book, The Burman: His Life and Notions.

“In his young days [the white elephant] was suckled by women, who stood in a long row outside his palace, and the honour was eagerly sought after… A hundred soldiers guard his palace, and the Sovereign of the Golden Throne himself makes offerings and pays him reverence… Every day he is bathed with scented sandal water, and all his vessels and utensils are made of gold. Troupes of the palace coryphées dance for his pleasure, and there are choruses of sweet-voiced singers to lull him to sleep.”

The 2001 capture of a white elephant by Ma Nu’s husband was followed by the discovery of two pale females in the same region in 2002. With their monarchical trappings, it is unsurprising that the deeply superstitious leaders of Myanmar’s military, then fronted by the brutal General Khin Nyunt, considered these animals to be particularly auspicious. The country’s last white elephant, after all, had died at the age of five in 1963, a year after the coup d’état that saw the Burmese army wrest control from a democratically elected government. Back in the 1960s, this was seen as a bad omen from the new junta’s point of view.

General Khin Nyunt planned to build a golden palace to honour the animals that blessed his reign. His dreams, however, were dashed when he was ousted, charged with corruption and placed under house arrest in 2004. In the aftermath of the internal coup, the general’s portraits were removed from the Royal White Elephant Garden, the animals’ assault rifle-wielding guards were reposted, the artificial waterfall built to soothe the restive creatures was switched off and the site fell into rusted and overgrown disrepair. Myanmar’s military elite, moreover, stopped bringing daily offerings, and the once-plentiful throngs of pilgrims dwindled to today’s trickle of curious locals and package tourists.

The neglect of the site was by no means an indication of growing secularism among the country’s leaders. A May 2010 article in The Irrawaddy suggests that General Than Shwe, the hardliner politician who seized power after orchestrating Khin Nyunt’s overthrow, implicitly discouraged his subordinates from visiting the animals that glorified his rival’s rule. Intensely superstitious himself, it seems that Than Shwe dreamed of having his own white elephants – perfect pale jewels to crown his newly minted capital, Naypyidaw, some 390km north of Yangon. When a white elephant was spotted in Rakhine state in 2008, a massive search was initiated, with soldiers, oozies and veterinarians scouring the region’s jungles alongside legions of coerced and unpaid villagers.

From the summit of the hill on which the Uppatasanti Paya stands, one can see the wide, empty boulevards and expansive construction sites of Naypyidaw stretching into a hazy and parched horizon. This city – the ‘Abode of Kings’ – replaced Yangon as the country’s capital in 2005. It is an artificial city, half-completed, concrete, and sterile; grandiose in vision, yet tacky in execution with its towering grey and white façades and manicured gardens – like a piece of American suburban sprawl transplanted to a sweltering plain, then accented with Asiatic flourishes.

Uppatasanti Paya, the golden centrepiece of the city, is a tawdry replica of Yangon’s magnificent 2,600-year-old Shwedagon Pagoda. Positioned at the foot of Uppatasanti’s eastern entrance, twin gilt-and-green pavilions overhang a small, forested ravine. A tall steel fence and a young policeman with a new Chinese assault rifle guard the three-tiered pavilions. Behind them stand Naypyidaw’s five white elephants.

The first two, both females, were captured in June and September of 2010. That November, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (a political party composed of former junta generals who traded their olive uniforms for dark business suits) won an overwhelming majority in the country’s “historic” and widely condemned general election.

In October 2011, two more white elephants – a male and a female – were snatched from their forest homes. All of these animals are perfectly pink, and all but one – much to the chagrin of the fiercely independent local Arakanese population – hail from Rakhine state. The country’s eighth white elephant, another female, was born in November 2011 to the animal caught the previous June.

Religious spectacles marked each of these animals’ arrivals in the new capital. Official statements declared that they heralded “improvement in the country’s foreign relations”, a successful “democratic transition” and that they are “a good omen when the State is endeavouring to build a peaceful, modern and developed nation”.

WHITE ELEPHANTS TODAY

The Thai royal family is thought to have at least ten white elephants in its possession. These elephants, which are rarely seen in public, might soon be joined by another – in April of this year, a young white male was spotted in the country’s Kaeng Krachan National Park.

With Laos’ last white elephant dying in Vientiane Zoo in 2010, Myanmar is now the only place where one can easily see these sacred animals.

Both Myanmar and Thailand currently possess more white elephants than at any time in history. Some see this as a sign of both countries’ promising futures; others believe that technological advancements and widespread deforestation are making it easier to flush out these pale creatures.

The Naypyidaw elephants appear docile, almost content with, or resigned to, their confinement. All but the calf are chained, yet none display their Yangon cousins’ nervous behaviour. The adults placidly pace as far as their fetters allow them. In its small pen, the energetic infant rushes about under its tranquil mother’s gaze, occasionally stopping to play with the dark grey elephant chained beside it for contrast.

The oozies in Naypyidaw seem intimate with their charges. They approach the elephants without trepidation to hand-feed them bits of sugarcane, caress their trunks and bathe them.

Elephant-wrangler Kyaw Aye, 23, captured the September 2010 elephant in his native Rakhine state. For his efforts, he was awarded a house in the new capital and a $120-per-month job caring for the animal. In past eras, men like Kyaw Aye were given land, money and titles and were exempt from taxation.

“I’m just happy to be living here with the white elephants,” Kyaw Aye says. “I make a good salary, and I can send money home to my family… This job is much easier than capturing wild elephants in the jungle.”

Steady streams of visitors come to observe the animals: pilgrims, bureaucrats, soldiers, businessmen, politicians, visiting diplomats and monks. The oozies supplement their incomes by selling laminated photos of the animals for about a dollar apiece.

U Aung Yin, 57, travelled more than 300km with a group of pilgrims to be there.

I’m glad to see them, but I also feel sorry… They were once free, but now they will never be able to go where they please.

U Aung Yin

Like the animals in Yangon, Naypyidaw’s white elephants spend their days on display and their nights roaming the small, forested grounds surrounding their pavilions. Unlike eras past, there are no gold adornments, no prostrating masses, nor are offerings of money, food and incense made. Still, one can’t help but think of the irony of these sacred beings – precious accoutrements of Myanmar’s new royalty trumpeted as celestial heralds of the country’s new beginning – being forced to live their lives in chains.

“They’re just diseased or genetically abnormal animals,” says Saw Yan Nhin, a renowned Yangon astrologer and numerologist. “They have no effect on the country.”

In his book-lined office near Shwedagon Pagoda, Saw Yan Nhin creates intricate maps of his clients’ lives and fortunes. Some, he claims, hold prominent positions in government.

“Traditionally, kings collected white elephants to promote themselves.” He believes that by glorifying its white elephants as signs of progress, the current government is taking advantage of the country’s uneducated masses.

“Education, sincerity and goodwill,” the mystic says, “are the only things that will improve this country.”