Jim Plamondon has a vision for a legal cannabis industry in Thailand. He thinks the plant will be legalised there for both medical and recreational use in a few years. He sees small farmers’ salaries being quadrupled. Small farmers could band together to form collective fields in which uniform varieties of cannabis are produced using large-scale agricultural equipment. He sees a range of products that could be developed, and said his company is in talks with Red Bull to produce an infused energy drink. He’s already thinking about merchandising, from vaporiser pens to bongs, plus dedicated Thai research into the plant and an expansion of the country’s already-strong medical tourism to include medical marijuana.

But most importantly, he sees a big market for exports.

“The goal is to dominate the global industry,” said Plamondon, vice president of marketing for the Thai Cannabis Corporation (TCC). For a decade, TCC has functioned as a think tank, conducting research on the potential medical and economic benefits of cannabis – currently an illegal substance in the country, punishable by a fine or up to five years in prison for possession of even small amounts.

Last month, the government made its first steps towards cashing in on the cannabis industry when the cabinet signed off on a draft law allowing cannabis to be used for medical and research purposes.

Globally, the medicinal cannabis industry is projected to be worth $55.8 billion by 2025, according to US consultant Grand View Research. If Thailand legalises, the country’s Ministry of Public Health would oversee a five-year pilot programme for legal medical cannabis, which could make Thailand the first nation in Asia to legalise – creating a dramatic financial boost.

“I’m doing this because it’s an opportunity for Thai people,” Jet Sirathraanon, chairman of the National Legislative Assembly’s standing committee of public health, told Agence France-Presse after he submitted the draft bill to the assembly in October. “Thailand has the best marijuana in the world.”

Jet is not the first to laud the quality of “Thai stick”. Thailand has long been known for its high-grade cannabis, which for centuries was used as a traditional Thai medicine before being criminalised globally in the US war on drugs. In the 1980s, it was among the top cannabis exports in the world. To this day, Northern Lights, a hybrid of Thai and Afghani landrace strains – indigenous, unaltered varieties of cannabis – is one of the most famous varieties of indica cannabis.

Straining to reach the top

Globally, cannabis is increasingly accepted as a treatment for ailments ranging from cancer and epilepsy to arthritis and migraines.

“The potential for cannabis-based medicines is increasingly clear as more clinical research emerges – so on that front, the argument for legalisation is simply one of access to medicines that have been shown to be effective, or to facilitate research to establish whether they are effective or not,” Steve Rolles, a senior policy analyst for Transform Drug Policy Foundation, told Southeast Asia Globe. “The problem has been that historically, drug war politics has hampered both research and access, a situation that is now, thankfully, beginning to change.”

While Europe and North America have been dipping their toes into legal cannabis – in October, Canada became the second country to legalise possession and recreational use of cannabis after Uruguay – Rolles said there remains a significant untapped market.

“Opportunities will no doubt grow as the market opens up, and those countries who are involved early will be able to establish an advantage going forward,” he said. “Thailand has the climate, workforce and technical knowledge to develop a significant medical cannabis production capacity if it chooses to. It would be able to do important research that would benefit patients around the world, and would be able to establish itself as a regional, if not world, leader in the field.”

“This is a tropical climate. This is where the stuff is supposed to be growing”

Jim Plamondon

Early in the legislative process, some government officials have seen the light. The Office of Narcotics Control Board previously granted permission for Rangsit University to possess and research medical cannabis, and the health ministry’s Government Pharmaceutical Organisation (GPO) is among those lobbying for legalisation.

“The best strains of cannabis in the world 20 years ago were from Thailand,” Dr. Nopporn Cheanklin, then-head of the GPO, told Bloomberg in July. But Canada’s legal market has had a chance to modify and improve strains, surpassing the gold standard once held by Thailand. “That’s why we must develop our strains to be able to compete with theirs.”

He added: “Thailand is not a country that likes to be the pioneer in the medical industry… but we certainly will not be the last country to do it.”

But Plamondon claimed the Thai government has been secretly preserving and improving 19 classic Thai landrace strains over the 40-plus years of the US-led war on the drug, putting Thailand in a better position to enter the market than the public might realise.

Even without that leg up, he said, Thailand’s production costs could give it a significant advantage over Canadian companies already leading the global market in cannabis production. Canada’s three leading cannabis companies, Aurora Cannabis, Hydropothecary and Aphria, were spending between 96 cents and $1.53 on production per gram of cannabis as of May, according to SmallCapPower statistics. Thailand’s projected production is 5 cents per gram, Plamondon said – “and we think in the long run, we could get it down to under 1 cent a gram…. That’s a tremendous advantage, and it’s not just because the cost of labour is low. It’s because this is a tropical climate. This is where the stuff is supposed to be growing.”

Thailand could be exporting $20 billion of cannabis by 2025 if exports are made legal

Proper sunlight and temperatures throughout the year would reduce electricity costs and allow for smaller plots of production year-round rather than the large single summer yields of North America and Europe. At the same time, Thailand’s minimum wage of roughly $10 a day significantly undercuts wages of farmers and trimmers in North America, where workers are often paid that rate or more per hour, he said. While creating the legal framework across international boundaries would be complex, Thailand could be exporting $20 billion of cannabis by 2025 if exports are made legal, Plamondon estimated.

The road to legalisation

The global cannabis sector is moving quickly, and Thailand must act soon if it wants to be a leader in the field, said Rolles of the Transform Drug Policy Foundation.

“There is no reason why Thailand could not produce and trade cannabis-based medicines internationally, as North American and European countries, for example, already do,” he said of medicinal products containing cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychoactive constituent of cannabis. “The longer Thailand, indeed Southeast Asia, more broadly, waits to enter the market, however, the more established the markets in the Global North will be, and the harder it will be to build market share against established corporate players.”

To go through the full legislative process could take up to three years, said Pascal Tanguay, an independent drug consultant who has worked on drug policy reform in Asia for 15 years. After parliamentary hearings, the plan would go to the Council of State, which reports to the office of the prime minister, for approval. If it passes this level, public hearings would be held before the prime minister’s office makes a decision, a process Tanguay said could quickly squelch the law’s passage.

“There’s a lot of reactive non-evidence-based beliefs that the average Thai holds about drugs,” said Tanguay, pointing to the country’s past approach to drug education, which has focused on demonising drug use. “That means that just the public hearings are likely to be a nail in the coffin.”

But even if domestic use is not yet cracked open, there is legal precedent to begin harvesting and trading cannabis internationally amid still-stringent domestic policies. Kratom, an opiate analog plant species native to the region heralded for its medicinal benefits – including its use by addicts to wean off of heroin – is included in the same draft law for medical use and research in Thailand. It is currently illegal to possess and consume across Southeast Asia. But Indonesia has created an exception that allows domestic production and exports, for which the US is a major buyer. In 2016 alone, kratom sales by 10,000 US vendors surpassed $1b, according to the Botanical Education Alliance. World Health Organisation guidelines on harvesting and dispensing medical plants help regulate the kratom industry.

“[Indonesia has] got a really cool model, because they’re essentially supplying the US. There’s about 40 million habitual kratom users in the US, and all of the kratom that goes to the US is sourced from Indonesia,” Tanguay says. “Once the model, the tools, the guidelines, the mechanisms are in place for one plant, it’s not that difficult to replicate for another plant [like cannabis].”

If medical use moves forward domestically, low-bar estimates place the value of that cannabis market at about 10% of all medical spending by patients in Thailand, said Kitty Chopaka, a representative for Thailand-based cannabis advocacy group Highland Network.

The country’s healthcare sector is exploding, buoyed by increasing medical tourism. In 2015, it was valued at $19 billion, and is expected to reach $28.5 billion by 2020, according to Alliance Experts.

But if domestic use is not pushed forward quickly, Thailand could miss out on becoming a medical cannabis hub – and it could hurt its medical tourism overall.

“If we’re taking too long, a neighbouring country may look into legalisation first, just for medical purposes or even production…. That means that we will lose out,” she said.

While the legislation is currently focused only on medical use and research, Chopaka said recreational cannabis could follow medicinal in a few years: “Let’s [take] Uruguay. Cannabis was legal countrywide for recreational use six years… before you [could] actually use it, because they couldn’t produce it or they didn’t come up with all the rules yet, and it takes time having all those in place. So Uruguay took six years, Canada took two years. I don’t know – Thailand can take between three and five.”

Rolles said wider legalisation would address issues that have grown alongside the prohibition that has failed to deter users: “It is an expensive and failed policy model that has only served to enrich criminal groups, make cannabis more risky due to the lack of labelling and quality control, and criminalise otherwise law-abiding citizens – in many countries, fuelling a prisons crisis and putting a huge burden on already overstretched law enforcers.”

According to research by Tanguay, government bodies from the Royal Thai Police down to the probation department reported spending upwards of $3.3 billion on compulsory and correctional drug treatment, drug prevention or reduction, and drug treatment in 2015. Of that, $2.99 billion was for drug enforcement – a huge chunk of Thailand’s annual $2.58 trillion national budget.

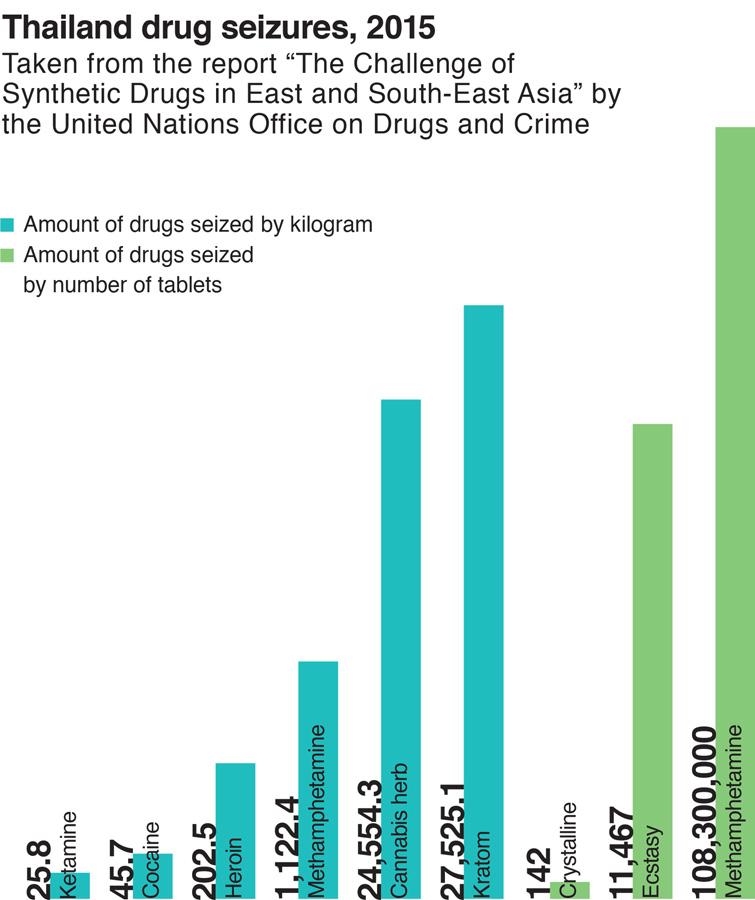

According to UN data, 7.2% of drug treatment admissions in Thailand in 2015 were cannabis-related. That same year, police seizures of cannabis totalled roughly 24,500kg – compared to 27,500kg of kratom, 200kg of heroin, 45kg of cocaine and 25kg of ketamine.

Set alongside methamphetamine – 1,100kg and an additional 108.3 million tablets, according to the same source – cannabis control is clearly not the government’s main drug issue, Tanguay said. “But still, cannabis would be the second or third most important drug in terms of seizures.”

Tanguay said that while the exact figure spent on cannabis enforcement isn’t clear, an estimate can be prorated based on these seizures and treatment admissions. If roughly 10% of arrests are for cannabis, he said, legalisation or decriminalisation would make around $300m currently spent on cannabis law enforcement available for drug treatment, prevention and “evidence-based response to drug control.”

By fully legalising cannabis, recreationally and medically, he said the government could also benefit from taxation. He pointed to UN reports of the $450m in tax revenues each year from cannabis coffeeshops in the Netherlands.

Regardless of how Thailand chooses to move forward, said Tanguay, one thing is clear: “The profit margins are huge.”