This article is the second part in our two-part look at practical solutions to the global plastic crisis. You can read the first part here.

Finding a practical use for all the plastic scraps choking our planet is an urgent step forward in addressing what has become a global crisis. In Southeast Asia, one company has elected to take the road less gravelled in search of a solution.

In China, developed countries had a dumping ground for their plastic waste for decades, with the country receiving nearly half the world’s output since 1992. Those days are over. In January 2018, China closed its doors to imports of non-recyclable waste, much of it plastic. The move was a game-changer for ASEAN, which has since “become the world’s new dumpsite,” Shanya Attasillekha from Greenpeace Thailand told VOA.

By the numbers, Asia is home to the world’s five top plastic-polluting countries: China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines. A 2015 study by the Ocean Conservancy and McKinsey Center for Business and Environment entitled Stemming the Tide concluded that if waste management were improved in these countries, the amount of global plastic hitting the world’s oceans could be reduced by 45% by 2025.

As it stands, Southeast Asian countries face a triple whammy of waste: exports from developed nations, debris washing up on its shores, plus its own domestic waste – all without the infrastructure it needs to deal with it.

The result is unsanitary waste littering roadsides and waterways, much of it everyday items like water bottles, which take up to 450 years to break down. Even waste that makes it to landfill sites can take a toll, with many landfills around the region being no more than open dumpsites.

The rising tide of plastic is a situation which countless communities across Southeast Asia face, and countries across the region are taking action: shipping waste back to senders by the ton and imposing bans on new imports. But while these measures have reduced the amount of waste piling up to a degree, they seem like little more than a drop in the ocean.

Take Indonesia, where plastic waste is estimated to reach 9.5 million tons this year to make up 14% of the country’s total waste. Government data shows that the country experienced an increase of some 140% in plastic waste imports in 2018, fast replacing China as the world’s number one destination for plastic. But no one country can fill China’s shoes when it comes to volume, according to Arnaud Brunet, head of the Brussels-based Bureau of International Recycling (BIR). “The problem is that the quantities involved are huge,” he told AFP.

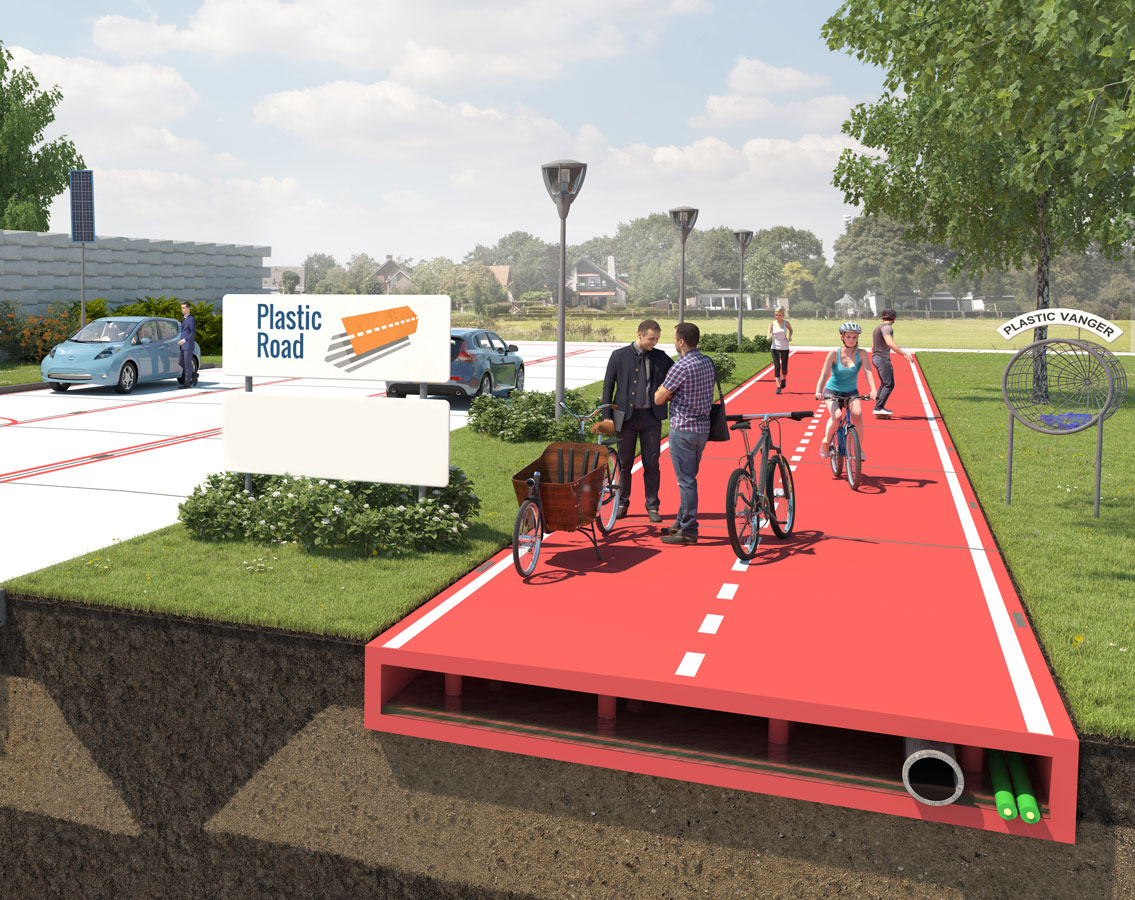

But one company has a novel use for all that surplus plastic: roads.

In 2017, American multinational chemical giant Dow Chemical company came together with the Indonesian government and four players from manufacturing, recycling and research to pave a road using plastic waste. Later that year, 3.5 tons of plastic was shredded, melted down and combined with asphalt to pave a 2km road in Depok city, West Java.

This was the first plastic road laid in Southeast Asia by Dow Chemical, who have to date paved a total of 100km of roads across the United States, India and Thailand.

Whereas Dow Chemical is laying plastic roads throughout Southeast Asia, the innovation first came from Rajagopalan Vasudevan, an Indian chemical professor who hit upon the idea of turning plastic into roads in 2001.

In Europe, the idea has been taken up by a handful of companies, including UK-based MacRebur and Netherlands-based Plastic Road EU.

Credit where it’s due; MacRebur CEO Tony McCartney admits he got the idea from watching waste pickers in southern India fill potholes with plastic they had retrieved and set alight. A common sight across Asia, these informal waste management workers sift through piles of scrap in search of material that can be sold for recycling. According to their website, MacRebur have since gone on to pave plastic roads from Australia to Dubai.

In Southeast Asia, the few kilometres laid by Dow Chemical in Indonesia could be the answer to the country’s bid to reduce its plastic debris by 70% by 2025, as pledged at the first UN ocean conference in June 2016. According to Dow Chemical, Indonesia’s total plastic waste could pave 190,000km of new roads across the nation.

Dow Chemical staff based in the region said that plastic roads were an elegant solution to the problem.

“The technology behind these new plastic roads has proven simple enough for wide scale application in Indonesia’s transport infrastructure,” said Bambang Candra, Asia Pacific commercial vice president, Dow packaging and specialty plastics in a December 2017 press release. “We are confident it will help manage the sheer volume of plastics waste the country produces.”

Dow intends to build on its proof-of-concept in Indonesia elsewhere in the region.

“We want to leverage the success in Vietnam,” Nguyen Hoai Son, the company’s corporate affairs manager in Vietnam, told Southeast Asia Globe in a phone interview.

It’s early days yet, with a memorandum of understanding signed in April this year between Deep C, the operator of an industrial park in Hai Phong on the outskirts of Hanoi, to complete a one-kilometre road by September 2019. The Deep C park will play host to the Vietnamese experiment and would constitute the first plastic road in the country, says Hoai Son.

As roads to redemption go, it’s a start. In Vietnam, Dow Chemical are perhaps best known for their part in the development of Agent Orange, the chemical defoliant which the US military dropped on Vietnam during the Vietnam War. According to the Vietnamese government, Agent Orange caused serious health problems for 3 million people, not to mention untold environmental damage to the 30,000 sq km which were denuded.

This may explain why Hoai Son insisted on the company’s national presence to be referred to as Dow Vietnam.

“When the bathtub is overflowing you don’t grab a mop, you turn off the tap”

GAIAs Claire Arkin

Today, the multinational ranks in the top three largest chemical producers, manufacturing plastics, chemicals, and agricultural products. The chemical giant claims to be in the business of minimising their environmental impact, says Nathan Kerns, senior marketing communications specialist at Dow US.

“We are working across our industry,” he said in an email to Southeast Asia Globe, “to find ways to make plastics themselves more environmentally sustainable and keep them out of the environment.”

In Vietnam, as in Indonesia and Thailand before, Dow will do this by leveraging the informal waste-picking sector and technology to scale up waste management efforts, and help rid Vietnam of its plastic scourge. Laying the road is expected to divert almost four tons, or one million pieces of flexible plastic packaging, including snack bags and pouches which might otherwise litter the environment or sit in landfill. The packaging will be supplied by Dow customers living near the industrial park, as well as from local waste pickers.

Kerns described the process from start to finish. “Waste pickers first gather waste, separate the hard-to-recycle plastic items and send those items to a recycler who shredded the plastic material into small pieces,” he said. “Those shredded plastics then are sent to local asphalt plants where they are added into the asphalt mixture.”

The plastic in the mix can displace 8-10% of the asphalt normally used, said Hoai Son. The asphalt is more expensive than plastic, with the savings for roads paved with plastic adding up to $1,000 per kilometre.

Plastic Free Southeast Asia founder Sarah Rhodes said that while plastic roads were new to her, her understanding was that when processed, the plastic converts to the exact same chemical makeup as bitumen. “If that’s true, then I think that it’s a good idea. It really depends on that,” she said.

But Robert Crocker, author of several books on waste and deputy director of the China Australia Centre for Sustainable Urban Development, thinks that paving roads with plastic is just kicking the can down the road.

“The chemical composition of the plastics and their additives can still leach into the environment,” he said. “Even if ‘sealed’ for ten years or so.”

Though still in the lab testing phase, things are looking good so far for Vietnam’s first plastic road, said Hoai Son. “The result is very good; better than a conventional road.” And according to Kerns, third-party research has found that roads enhanced with plastics are 15-33% more durable.

“Additionally,” he said, “by extending the service life of the road, they also reduce resurfacing frequency which can lead to less traffic interruption and additional reductions in energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions.”

Not everyone’s convinced. When it comes to emissions, environmentalists have raised concerns about toxic substances which could be released from plastic residues melted down to create the new paving mix. Indian chemical professor Rajagopalan Vasudevan, who first hit upon the idea of turning plastic into roads, attempted to allay these fears in an interview with the Guardian in July 2018.

“Plastic decomposes to release toxic fumes only if it is heated at temperatures above 170C,” he explained. “So there is no question of toxic gases being released.”

Hoai Son said that two types of plastic do not make it into the mix on health grounds. “We don’t use a PVC [or] plastic with aluminium inside,” he said.

But every other type of plastic is eligible for processing into road surfactant, including the ubiquitous shopping bags which are the scourge of Southeast Asia’s waterways.

The acceptance of pesky plastics is key, said Dow: it benefits Vietnam’s informal waste pickers, who currently cannot sell these non-value plastics. Rather than discarding these plastics back to landfill or openly dumping them, the waste collectors have a buyer in Dow, making plastic roads win-win.

“We not only turn non-value plastic waste into a value product,” Hoan Soi said, “but also show that the related stakeholder, the asphalt blender, [and] the investor can save money.”

When it comes to cutting costs on processing plastic, now is the time. The price of plastic waste hit rock bottom following China’s import ban as Hiroshan Hettiarachchi, an academic on civil engineering and sustainability at the United Nations University in Germany, told Southeast Asia Globe.

“So if there is anyone interested in investing in plastic processing it’s a good opportunity,” he explained. “Because the raw material is cheap now and the labour is inexpensive.”

“I am sure more circular initiatives are always good, and we really need more environmentally friendly plastics. But I am sceptical that corporations making plastic can solve this problem”

Robert Crocker, deputy director of the China Australia Centre for Sustainable Urban Development

Falling costs of production could pose a major threat to the environment, in Crocker’s view.

“Increasing efficiencies in production over time lower costs – and, eventually prices and margins – encouraging both more consumption and more volume production for consumption,” he said.

Paving roads with plastic breaks the mould when it comes to addressing plastic pollution. Up to now, efforts have focused on one of three categories, known as the three R’s: reduce, reuse and recycle, the last being the most dominant R in Southeast Asia. But heads of the recycling industry say that from now on, the name of the game should be a new R: recover.

In Brunet’s words, Western countries should “invest in research and development of more detailed and efficient sorting systems” which can churn out useful raw materials.

Emerging solutions to plastic pollution are welcome, said Crocker, though he still had reservations.

“I am concerned that many of the projects I have seen [such as paving roads with plastic] simply ‘park’ the plastics in an existing material and then, supposedly, turn it ‘green’,” he said. In reality, he said, this plastic would remain “parked… until the end of the life of the roadway, and then the same kind of problem emerges”.

Dow has set its sights on expanding plastic roads elsewhere in the region, working up technical capacity in Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia alongside governments to development guidelines on how to make plastic roads.

Paving roads with plastic seems a step towards fulfilling Dow’s self-professed sustainability goal of creating a circular economy, in which no plastic is wasted at any point in its life cycle, by 2025.

To this end, Dow Chemical is one of 36 global companies in the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW), an organisation investing over $1 billion and aiming to raise another $1.5 billion to develop and scale solutions to minimise and manage plastic waste the world over. Dow Chemical is one of several plastic producing companies in the Alliance which also includes waste management giant Veolia, beverage multinational PepsiCo and three multinational oil and gas companies: Shell, ExxonMobil and Total.

Crocker had mixed feelings about the AEPW. “I am sure more circular initiatives are always good, and we really need more environmentally friendly plastics,” he said. “But I am sceptical that corporations making plastic can solve this problem.”

Claire Arkin, communications coordinator for the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, had similar reservations.

“The companies in Alliance to End Plastic Waste are the same companies responsible for the out-of-control production of single-use plastic,” she said. “They have invested $1 billion in this project while at the same time the industry has invested over $200 billion in the US alone to expand plastic production infrastructure.”

For Crocker, real change issues from the seat of government. “The role of economic incentivisation and regulation cannot be underestimated,” he said. “And companies do not usually want to support these more structural, policy-driven initiatives.”

While initiatives like AEPW may have a role to play in addressing plastic pollution, it may not be enough. Plastic production is expected to quadruple by mid-century, according to 2016 data for the World Economic Forum – and if today’s trends continue, most of that will wind up in Asia.

What’s more, Grand View Research, a market research and consulting company based in San Francisco, finds that global demand for plastics is expected to increase by a third between 2013 to 2020, from some 200 to 300 million tonnes.

“These and other investments are aimed to quadruple plastic production by 2050,” said Arkin. “When the bathtub is overflowing you don’t grab a mop, you turn off the tap.”