This article is the first part in our two-part look at practical solutions to the global plastic crisis. You can read the second part here.

“Imagine yourself sitting on a beach. Feel the waves lap up against the shoreline, feel the wind rustle through the palm trees overhead,” said Marianne Teoh, Cambodia marine programme manager at conservation organisation Fauna & Flora International (FFI). In early 2019, Teoh was the keynote speaker at an event organised by the European Chamber of Commerce (Eurocham) in Phnom Penh to speak about private sector solutions to the plastic challenge.

“Now open your eyes.”

Worldwide, an estimated 8 million tons of plastic end up in our oceans each year. Ton-for-ton, said Teoh, that’s the equivalent of “over 26,000 Boeing 747 planes running into our oceans every single year”.

This throw-away ethos is adding up – and fast. By 2025, there will be one tonne of plastic for every tonne of fish in our oceans, says a 2016 World Economic Forum report. By 2050, there will be more plastic than fish.

And people are starting to get the message. Concerned consumers the world over have taken matters into their own hands by shunning plastic bags and packaging in favour of earth-friendly alternatives.

As the science mounts, so does alarm about the hazards of plastic on land and at sea, where it leaves a particularly toxic trace: microplastics. These minute particles are all that remain of larger pieces of plastic, including microbeads in beauty products and microfibre towels.

The reality is hard to swallow. New analysis by researchers from the University of Newcastle in Australia commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) suggests people are consuming about 2,000 tiny pieces of plastic every week as these microplastics enters the food chain through fish, seafood and crops. To put that in perspective, that amounts to about five grams, or the weight of a credit card, each week – more than 250 grams every year.

While the jury is still out on precisely what impact microplastics may have on your health, it is known that eating and drinking out of plastic containers can wreak havoc with our hormones, with stark consequences on our reproductive systems.

Speaking at the Eurocham event, ecological economist Taber Hand was more forthright about health impacts, taking aim at single-use plastics.

“Until plastic as a single-use entity is classified as a toxic material,” he said, “we’re not going to get too much farther on stopping the use of plastic.”

When it comes to plastic pollution, it’s not just people that suffer. Ocean plastic is having a significant impact on marine creatures. And it’s hard to overstate how wide the problem reaches.

“Plastic bags, nets, sandbags and concrete bags [are] underwater smothering coral reefs and killing these vital ecosystems,” said Teoh.

Ultimately, it’s not only ecosystems which pay the price of marine plastics, but the planet’s climate as a whole. According to a new report, Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet in May this year, the world’s oceans absorb as much as 40% of all carbon dioxide produced by humanity since the start of the industrial era.

“A small but growing body of research suggests plastic discarded in the environment may be disrupting the ocean’s natural ability to absorb and sequester carbon dioxide,” stated a press release from the Center for International Environmental Law, one of the report’s authors. Together with other emissions sources, it said, this could threaten “the ability of the global community to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°C degrees”.

Meanwhile in Southeast Asia, scenes of putrid pollution and beached marine creatures bloated with plastic continue to prompt international outcry.

While the crisis is worldwide, the problem is primarily Asia’s, which has become the destination for 75% of the world’s waste – much of it plastic. In light of this, and the region’s meagre waste infrastructure, it’s not surprising that countries in Asia are the biggest ocean plastic polluters.

What’s more, the world over, only a tiny amount of plastic ever makes it to processing facilities – ever. According to Claire Arkin, communications coordinator for the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), “of all the plastic that’s ever been made… a mere 9% has been recycled.”

Organisations like GAIA, which is made up of some 800 grassroots groups, NGOs, and individuals from over 90 countries, are calling out the real plastic polluters. “Countries like the US, Australia, and the UK generate much more plastic waste than countries in Southeast Asia,” explains Arkin. “They have also been exporting their waste abroad for Asian countries to deal with under the guise of ‘recycling’, passing both the burden and the blame for the resulting pollution.”

“Incinerators need to be fed a large diet of waste in order to survive. Once built, they are built to burn waste for decades”

GAIA communications coordinator Claire Arkin

So while waste is out-of-sight-out-of-mind for developed countries, Southeast Asia is saddled with the pollution, which takes a serious toll on people and planet.

And while sending waste back, as Cambodia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia have started doing, sends a strong message to plastic-exporting countries, it chiefly covers newly arrived plastic stuffed in shipping containers – much of it mislabelled. What about the plastic waste already out there?

Waste not, want not

For Holger Borchert, founder of the Hong Kong-based social enterprise Asian Plastic Opportunity (APO) this is where technology comes in.

Globally, waste-to-energy is a nascent industry rapidly picking up speed. Proponents argue that returning waste materials to the sum of their parts could lay the foundations for a circular economy, a closed economic system which minimises waste while maximising resources. In the case of plastic, the energy locked up in plastics materials can be used multiple times, without the need to extract more fossil fuels.

While Borchert recognises the need for nations to clean up their act, for him current efforts to reduce, recover and recycle plastic waste are not enough. The most important thing, he said, is to “take care of the plastic waste that is already out there”.

“If it’s not treated well, it will end up in the sea,” he said.

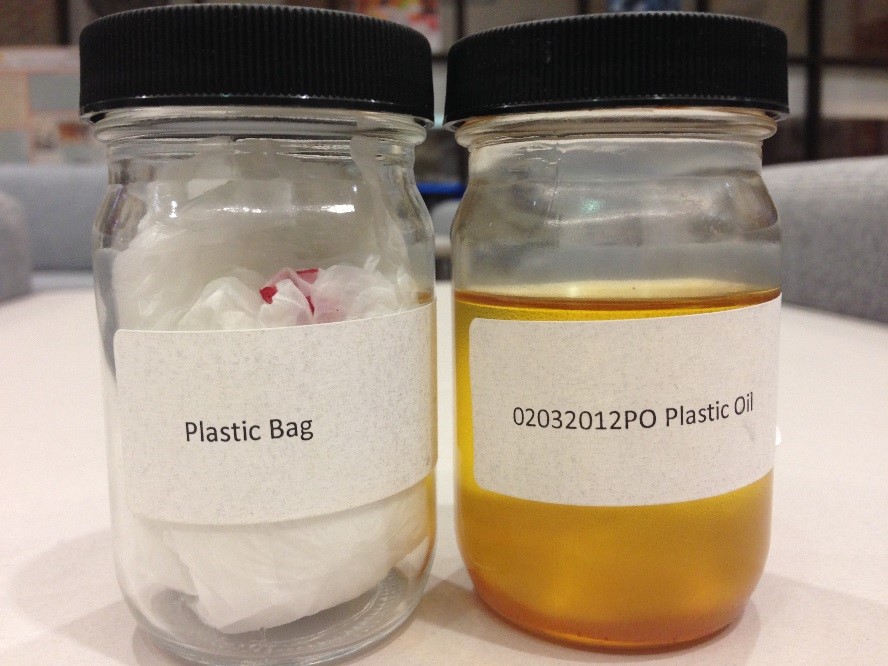

So rather than sending plastic waste back to whence it came, the answer lies in returning the plastic itself to its raw materials: fossil fuels. By reducing plastic to its components, these raw materials are made available in the form of gas and oil.

This means first collecting plastic waste before sorting, cleaning, drying, and treating materials at high temperatures to yield liquefied natural gas or methane which can be used in household cooking, among other things.

And APO has plans to deliver custom self-contained units to the site where pollution occurs, bringing jobs into waste-stricken communities who can take waste collection and management into their own hands.

“Local waste treatment will avoid this heavy pollution in the future, as waste becomes a source of income and energy for local communities,” he said.

But it all starts with cleaning up waterways – something which Borchert’s APO and German NGO One Earth One Ocean (OEOO) of which Borchert is a member, have been active in.

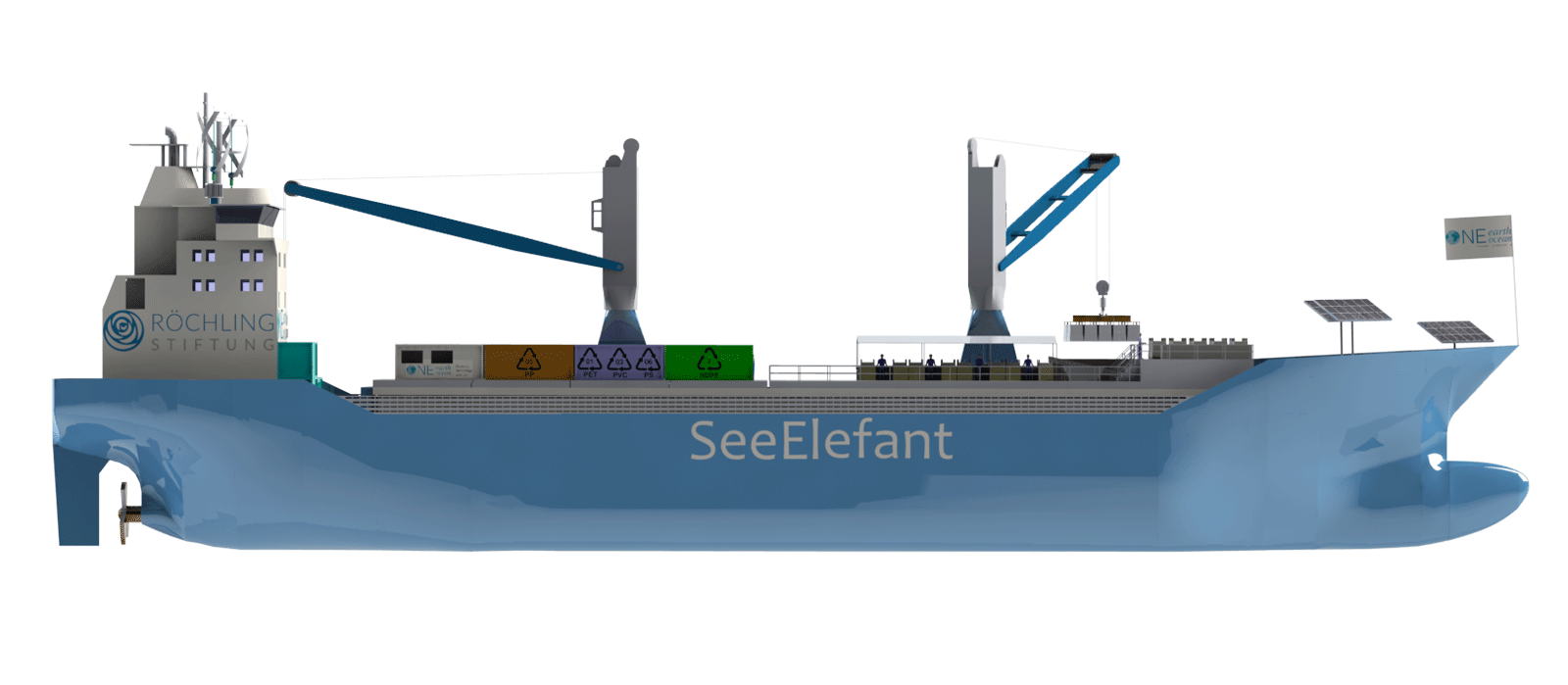

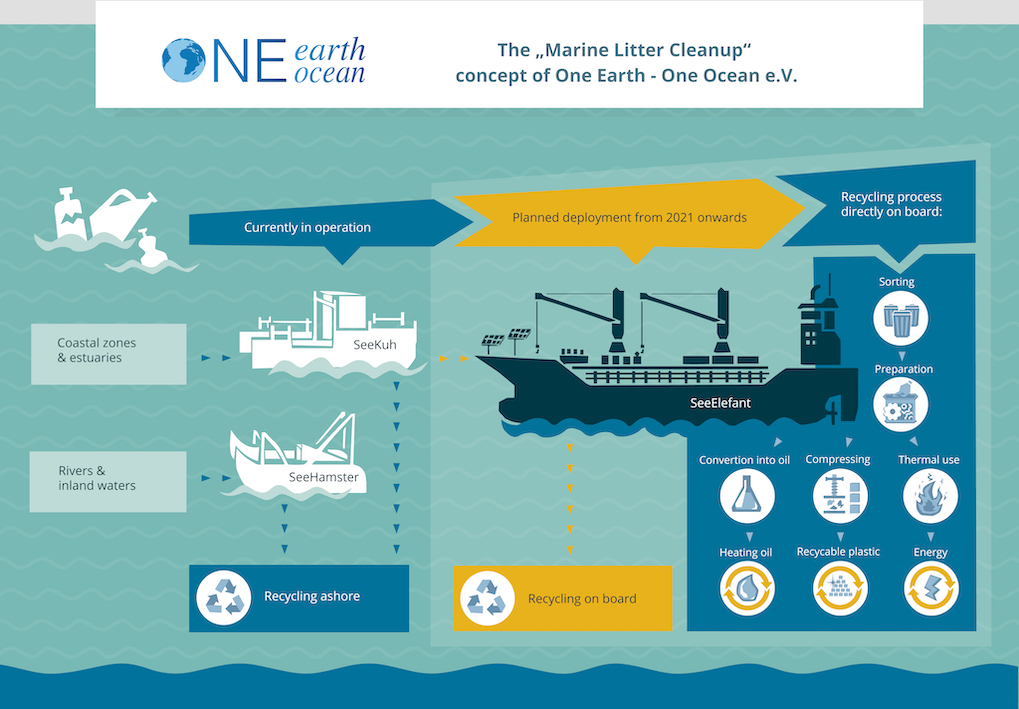

OEOO aims to eliminate pollutants from water bodies worldwide – including plastic – with the help of specially designed waste collection boats. The first of these was trialled in European waters back in 2012. Six years later, the custom built “SeeKuh” catamaran sailed into Hong Kong harbour at the beginning of 2018 and spent the next six months removing waste from the surrounding waters.

The custom-built catamaran takes its name from the distinctive dugong or “sea cow”, a majestic marine mammal that has all but disappeared from Hong Kong’s waters. At its peak, the SeeKuh fished out close to 50kg of waste in five minutes, Günther Bonin, OEOO founder told Southeast Asia Globe via email.

“But our work in Asia must be continued,” he said.

The city of Battambang in northwest Cambodia is OEOO’s next stop. Home to almost 200,000 people, the city sits on the banks of the Sangkae river, which feeds the Tonle Sap lake and in turn the Mekong river, waterways which tens of millions of people rely upon. OEOO sees Battambang as “one of the most important projects worldwide to proof the feasibility of marine litter cleanup”.

The Sangkae river will be a testing ground for their SeeHamster, a “small waste collecting ship for rivers and inland waters” that doubles as a transport tuktuk on land. According to Bophaphal Sean, head of operations at OEOO’s local partner organisation, German-Cambodian NGO COMPED, the SeeHamster crew can pull out around 200kg of waste per day from the river, which is then separated into different plastic types.

This is just the beginning. OEOO has plans for a so-called SeeElefant, which Bonin described as “a multi-purpose ship with recycling equipment on board” capable of processing around 20 tons of plastic waste, with hopes to one day increase this ten-fold for commercial operations.

This larger ship would be a world first, according to OEOO’s naval architect Lennart Rölz. He told Southeast Asia Globe that the ship could work in harmony with the SeeKuh and SeeHamster.

“The smaller collection vessels can completely be electrically supplied via the SeeElefant,” he said. That’s because, like APO, OEOO are planning to recycle they collect onboard the ship itself, producing oil to power the rest of the fleet – as well as keeping the ship itself afloat. “Our calculations show that about 60% of the required energy of the SeeElephant can be obtained from the plastic,” said Rölz.

According to Bonin, the key is thinking of plastic waste not as an insurmountable problem, but merely “a raw material made of crude oil”.

This kind of thinking is troubling for both the people and the planet, said Arkin. According to Arkin, the technology behind waste-to-energy projects like those outlined by APO and OEOO involves incineration, which produces toxic emissions which “could threaten human health and the environment”.

Waste incinerators are by no means a new technology. A 2001 Greenpeace report raised the alarm on their health hazards, finding that people living near incinerators in England, Spain and Japan were exposed to cancer-causing dioxins, also linked to birth defects and immune system damage, as well as mercury, which is known to disrupt the nervous system and affect brain development in children.

The report challenged the belief that incinerators eliminated waste, stating that “incinerators do not destroy waste but convert it into other forms – gases, ash and dust particles.” Incineration technology has come a long way since the turn of the 21st century, but a 2010 study by German researchers found that even the latest incinerators released high levels of dioxins.

What’s more, if the aim is to avoid planetary crises, such as plastic pollution and climate change, incinerating plastic should be avoided along with fossil fuels, said GAIA’s Arkin.

“At a time when we desperately need to keep fossil fuels in the ground, these processes are merely a more convoluted way to burn them,” she said.

Incinerating plastic “is the worst waste management method for plastic from a climate perspective,” she continued, adding that the practice results in “almost one ton of greenhouse gas emissions per ton of plastic burned.”

In fact, when it comes to impact, the environmental impact of plastics is not too dissimilar to that of coal. “In 2019 alone,” Arkin explained, “the production and incineration of plastic will add the same amount of pollution as 189 new 500-megawatt coal-fired power plants”.

This pollution could soon rise if Indonesian President Joko Widodo has his way: while announcing a radical shift in national energy policy to “start reducing the use of coal” at a cabinet meeting held on 8 July, eight days later he decried the lack of progress in constructing waste incinerators.

Waste-to-energy plants seem like a way for Indonesia to kill two birds with one stone: reducing the use of coal at the same time as reducing the volume of waste which ends up in the sea by 70% by 2025. But Widodo is thinking only of the latter. “This isn’t about the electricity,” he said in a government-issued statement following a 16 July cabinet meeting. “We want to resolve the trash issue; the electricity comes afterward.”

The energy ministry plans to have 12 waste-to-energy plants up and running by 2022, which would collectively burn 16,000 tons of waste a day to generate 234 megawatts of electricity.

A lost opportunity?

Borchert argues that in addition to the social and environmental costs, our current management of plastic means we’re losing out on the materials’ potential.

“Since plastics have an energy value higher than coal,” Borchert said, “the landfilling of end-of-life plastic waste constitutes a loss of an important energy resource.”

But the high temperatures required to unlock the gas and oil within plastic make incineration an energy-intensive process – and therefore a dead end, said Cambodia-based Hand.

“The idea of taking plastic and burning it to produce energy or to produce oil is, from an energetic context, not very smart thing to do,” he said at the Eurocham event. “And if we’re talking about a sustainable world, that’s not a practice we should follow.”

And the energy-intensive nature of waste-to-energy endeavours actually throws up a barrier to their execution. “Incineration practices like gasification and pyrolysis are incredibly costly,” said Arkin. “Our research has shown that they tend to fail financially, and are also prone to technical failure.”

Sure enough, both APO and OEOO are facing financial hurdles. Bonin explained that while the technology exists and is being used already in Germany, it isn’t scalable to an industrial level yet, and the vessels need refinement – not to mention investment – before they can be dispatched to remote parts of the world.

Ship builder Rölz detailed the cost of the pilot SeeElefant: €12 million, or $13.5 million. A small price to pay, he said, compared to the €13billion, or $14.5 billion which marine litter costs in economic damage every year.

So for now the SeeElefant remains a dream, with the first prototype planned for 2021, said Bonin.

But help is on hand for cash-strapped waste-to-energy prospectors. While Indonesia has voiced support for projects, the Thai government has gone one step further by establishing subsidies and tax incentives for a diversity of waste-to-energy plants, including those which rely on incineration.

Nationally, the installed capacity stands at just over 200 megawatts (MW), with licenses granted for a further 500MW waste-to-energy plants. Both APO and OEOO are eyeing up Thailand as a possible base of operation for future industrial recycling plants. In neighbouring Cambodia, APO plans to install their first plant at the beginning of 2020, with a scheduled capacity of 20 tons per day. “In the end,” Borchert said “we plan to operate a plastic recycling unit and another plastic to oil/gas aggregate.”

Despite the challenges, he remains resolute about APO’s plans to take on plastic pollution.

Passed down for generations

While Borchert was quick to acknowledge the hazards of plastic, which he described in a phone interview as “the most harmful product on earth,” he stuck to his guns about the merits of removing and recovering value from plastics which otherwise would be “out there for generations”.

The problem is that investment in incinerators would likewise last generations. “They need to be fed a large diet of waste in order to survive,” said Arkin. “Once built, they are built to burn waste for decades.” Waste-to-energy technology may represent a shift, but not one in the right direction, she added. “Incinerators are an investment in the status quo – making, taking, and wasting… We don’t have any more time to waste on this polluting system.”

Bridget McIntosh, Cambodia country director of EnergyLab, agreed that waste-to-energy was not the way to go.

“In my opinion, waste-to-energy is the last solution to our resource and waste system,” she said.

For her, the key lies in smart design.

“The circular economy concept starts by designing products well to last long and be modular to easily replace parts or repurpose or recycle parts,” she said. “If it can’t be fixed, shared, repurposed, reused or recycled then it should be used for energy or lastly landfill.”

But efforts to address plastic pollution in the region are gaining traction. On 22 June, ASEAN issued the Bangkok Declaration calling on member states and partners to “prevent and significantly reduce marine debris, particularly from land-based activities, including environmentally sound management”.

While Greenpeace applauded this display of regional action on a common challenge, the environmental organisation remained skeptical. “The issue is not how to manage plastic waste so they don’t end up as marine debris,” the organisation said in a statement “but how all nations must focus upstream, and drastically reduce plastic production.”

With this in mind, “techno-fixes” like incineration are “at best distractions from the real problem – over-production and consumption of plastic,” said Arkin.

“The solution [is] to drastically reduce the amount of plastic in the world,” she said.