ON 20 JANUARY 1959, a ten-year-old Sam Rainsy watched as the police raided his family home in search of his politician father, Sam Sary, who had been accused of treason. Sary had already fled Cambodia, the police soon learned, making the length of rope they brought for the occasion useless. They had planned to do to Sary what they had done to another politician accused of treason, Dap Chhuon.

“After being shot, [Chhuon’s] body was dragged through the streets of Phnom Penh at slow speed by a military vehicle. The blood-covered corpse slowly disintegrated until nothing recognisable remained,” Rainsy wrote in his memoir, We Didn’t Start The Fire, in which this story appears on the very first page.

On 13 November 2015, a 66-year-old Rainsy was faced with a similar, albeit far less perilous, situation. The president of Cambodia’s largest opposition party, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), was meeting with supporters in South Korea when a warrant was issued for his arrest in connection with a seven-year-old defamation case. With the subsequent addition of more charges in separate cases, he faces up to 18 years in prison.

Rainsy has long employed self-exile as his form of habeas corpus, and he decided, yet again, to remain abroad rather than return to stand trial. This is the fourth time he has made such a choice, including a stint spent mainly in France between January 2010 and July 2013.

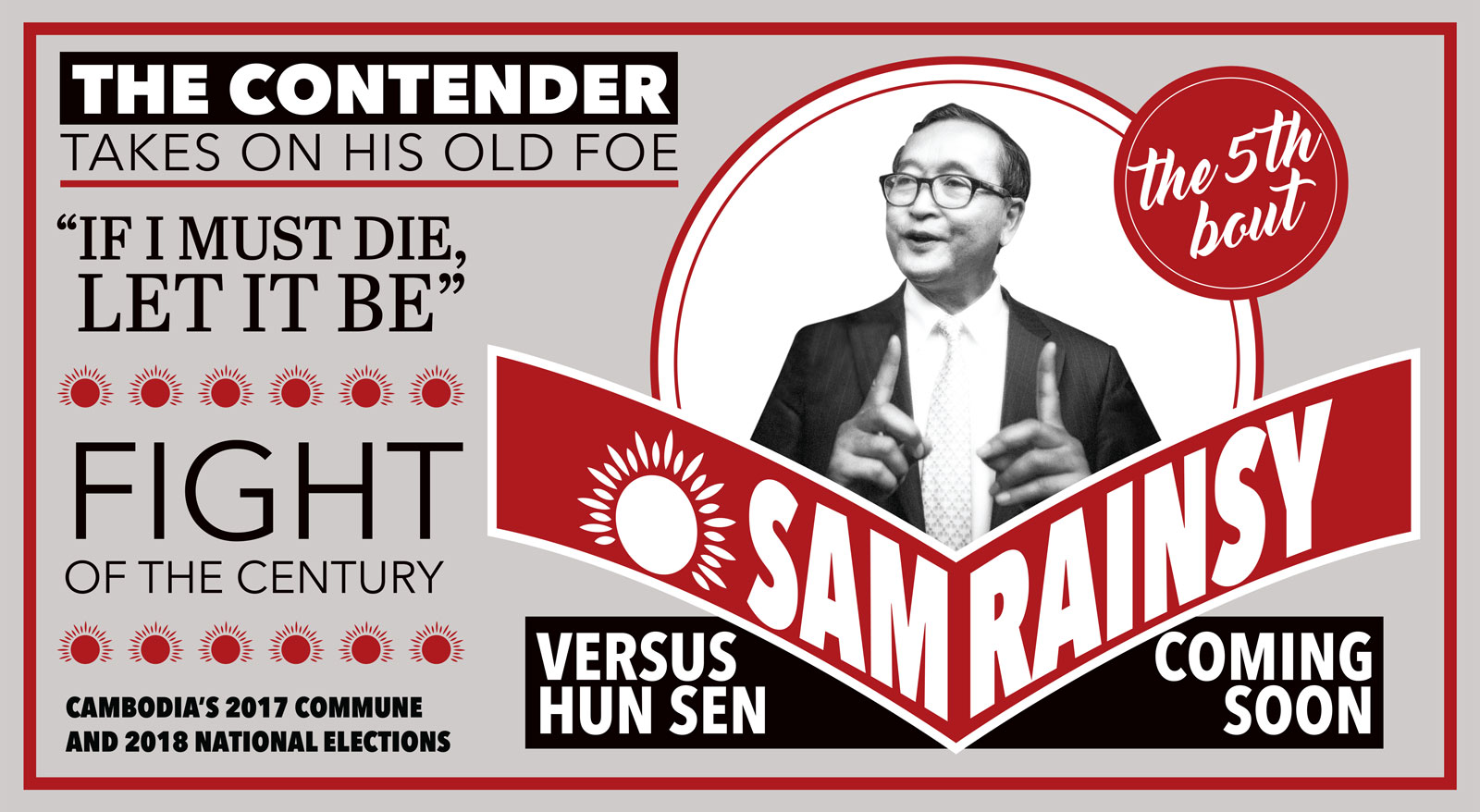

Sok Eysan, a spokesman for the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), derided him as a “coward”, according to the Cambodia Daily, though the opposition leader was probably not helped by his own volte-face. The day after his arrest warrant was issued, he announced: “I absolutely must go back and rescue our nation,” before adding, “If I must die, let it be.” Two days later, he declared he would not be returning and, instead, set about touring the world, taking occasional selfies aboard yachts and with foreign dignitaries.

However, self-exile has worked well in the past for Rainsy. Weeks after returning to Cambodia in July 2013, his CNRP secured 55 seats at the national election compared to the CPP’s 68. The CNRP faithful still claim the vote was rigged, but the result was an undeniable success in a country where all opposition parties combined won just 33 seats in the previous election.

Mu Sochua, a CNRP member of parliament for Battambang province, claims that Rainsy’s departure has had little impact on the party. “The party structure continues to work as usual,” she said, adding that when CNRP politicians visit supporters across the country, laptops are regularly set up so Rainsy can still communicate directly with the people he hopes will vote for his party at the commune elections in 2017 and the national elections in 2018.

“Rainsy’s exile has become a common thing in the Cambodian political arena. It’s not too surprising,” said Preap Kol, executive director of Transparency International Cambodia. He added that Cambodians are “getting used to the scene of Tom and Jerry”.

Furthermore, most commentators agree that Rainsy’s disappearing act is a mere sideshow in the CNRP’s much larger, inefficacious performance.

“The CNRP has no real platform, no real structure in place to take power and no real policies,” said Ou Virak, a political analyst and founder of the Future Forum think tank. “There are promises, but there are no people who have focused on policies and become experts. So there’s no possible minister of health, education, transport, energy, et cetera. That has long been a problem.”

The CNRP would deny this, as Sochua did, pointing to the seven-point platform on which they campaigned at the 2013 election and adding that the party will announce a new one soon. The points included raising the wages of garment workers and civil servants, lowering fuel and electricity costs, introducing universal health care, reforming the judiciary and ending corruption.

However, Cambodian politics have shifted in the intervening years. “The CPP was so arrogant and out of touch with the public that it ignored any calls from the public for change [before the 2013 election],” Virak said.

In fact, the CPP’s reaction to coming close to losing the election has been a recognition of its faults and the emulation of the opposition’s strengths.

In October, the government raised garment workers’ minimum wage to $140 per month, effective from 1 January this year. In November, Prime Minister Hun Sen announced that the wages of civil servants will increase each year, reaching $250 a month by 2018 – despite comments in 2013 that this would be impossible. In January, new legislation for comprehensive health insurance for formally employed workers was signed. The government has also made strides to reduce fuel and electricity prices, such as a proposed fuel-pricing mechanism to create a government-calculated price limit on petrol at the pump.

“The CPP was smart: they saw the CNRP’s promises drew a huge amount of support to the opposition. So, naturally, they’ve moved to steal their thunder,” said Sebastian Strangio, journalist and author of Hun Sen’s Cambodia. “But the CPP, unlike the opposition, is actually in a position to improve people’s lives right away… By appropriating the opposition’s promise, the CPP has bolstered its claim to legitimacy.”

The CPP’s wooing of opposition voters does not end there. Hun Sen’s avuncular efforts to appeal to younger Cambodians via Facebook have intensified in recent months – on the day of writing, his two million-plus followers were feted with photographs of him clad in khaki shorts and shirt, watering the flowers in a park just outside his palatial residence.

For many years, social media was the opposition’s terrain, allowing them to connect with their core voters – the young and urban. By the 2018 election, more than 60% of Cambodia’s population will be aged under 30, and this is a key demographic the CNRP has long assumed is on its side.

Imitation might be the sincerest form of flattery, but it could cost the CNRP votes and its chance at winning power in 2018. According to Virak, while the CPP shows some signs of reform, similar efforts to move on from 2013 are not being made by the opposition. “They need to redouble their efforts to catch up, or else they might lose their position,” he said.

“The CNRP is not perfect, but we are optimistic about the future and trying to make changes,” said Long Botta, a veteran politician who served in the cabinet of Norodom Sihanouk in the 1960s and, now, a CNRP member of parliament for Battambang province. For the past few months, he tells Southeast Asia Globe, he has been preparing for next year’s commune elections.

Typically, these are dominated by the CPP. At the 2012 commune election, where villagers vote for their local representatives, 1,592 out of 1,633 village chiefs elected were from the CPP.

However, Botta is confident ahead of 2017. “We would be happy with 40% of votes,” he said. “But with the widespread fraud and corruption of the CPP at commune level, it’s more difficult for the CNRP to win the communes than the legislative.”

The opposition is selecting fresh candidates – as many as 40% will be new, according to Botta – as well as intensively vetting them for commitment and “good behaviour”. Botta added that while the ruling party has tried to appeal to traditional opposition voters, and might succeed in winning some over, the reverse is also true. “The CPP is still doing land grabs, deforestation and corruption, which angers people, so we will win some voters from them, too,” he said.

While commentators say that the CNRP would benefit from serious introspection, actually winning the next national election and taking power might be out of its hands.

“There are two questions,” Strangio said. “Would the CNRP win a free and fair election, and would the CPP permit it to take power?” He added that the former might be possible, but expressed scepticism about the latter.

One major issue is a lack of separation between the state and the CPP. The 1991 Paris Peace Accords tried to enforce a separation, so that appendages of the state, such as the military, police and judiciary, would not be controlled by the CPP. This attempt, commentators say, failed.

Kol said that many Cambodians, particularly those in the countryside, do not understand the difference between the state and the CPP. When schools or hospitals are built using state funds, for example, they often bear the name of the prime minister or other CPP nomenklatura. The purpose of the state to provide for its citizens is, therefore, confused with merit-earning handouts from the CPP.

There are also allegiances to consider. As Chea Dara, a four-star general, told military commanders in July: “Every soldier is a member of the People’s Army and belongs to the CPP.”

Hun Sen said in an October speech that if a CNRP government tried to remove the CPP loyalists in charge of the armed forces there would be an “internal war”. Similar threats were made if a victorious CNRP attempted to prosecute CPP-aligned tycoons accused of land grabs and corruption.

“It’s to do with the patronage system of Cambodian politics, which inhabits and subsumes organisations,” Strangio said. “Assuming the CPP permitted the CNRP to win [an election] and take office… [CNRP] would face huge challenges in eradicating this patronage network that has been built over 30 years, creating their own patronage networks or creating a more rational civil administration. I cannot see how they would solve it.”

“Cambodians deserve better,” Virak recently wrote in the New York Times of the country’s political system. The commune and general elections will be the real test for the CNRP, and opinion is divided over the outcome. Virak feels that the momentum that secured the CNRP 55 seats in 2013 is fading, but the CPP’s energy is not.