For Papuan activist Yanto Arwakion, life behind bars has become all too familiar. He is just over halfway into a one-year sentence on charges of treason, his third stint in jail since 2012.

“Every day behind bars I only sleep or read books and the Bible,” he said in a Whatsapp message sent to Southeast Asia Globe from his prison cell in Timika, a city in Papua.

Describing jail conditions as spartan and run-down, Arwakion said that though having a mobile phone is forbidden in jail, prison guards are more concerned with money than rules.

“I was arrested and later jailed because I am the leader of an organisation that voiced the aspirations of the Papuans to the international community: that Papuans need to be independent because of history,” he said.

Papua refers to the western half of the island of New Guinea, and incorporates the provinces Papua and West Papua. Independence activists and many people outside of Indonesia usually refer to the entire region as West Papua.

The organisation Arwakion is referring to is a branch of the National Committee for West Papua (KNPB), a student-led rights group established in 2008 that campaigns for self-determination for the indigenous people of Papua.

The territory has officially been part of Indonesia since a UN-backed referendum on 17 August 1969, known as the “Act of Free Choice”. But out of a population of roughly 800,000, the Indonesian military picked just 1,026 people to vote, leading many Papuans to label it “The Act of No Choice”.

On the 50th anniversary of the vote, independence supporters such as Arwakion have no intention of giving up the fight.

“I am a native Papuan and therefore I have the right to fight for my life without any intervention from anyone or any country,” he said.

The raids, the arrests and the lawsuit

Arwakion said that he was preparing for a traditional feast and prayer to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Timika branch of the KNPB on 31 December last year at the group’s headquarters when Indonesian security forces stormed in and arrested him and two others while taking the building.

The activist’s lawyer, Gustaf Kawer, hit out at the raid and the subsequent arrests. “The police did not show any warrants and, in early investigations, [the accused] did not have a lawyer,” he said.

“They are currently being jailed in prison cells with poor conditions and their family members do not have proper access to visit them.”

The arrests were part of a series of raids on KNPB branches carried out as Indonesian security forces sought to clamp down anew on pro-independence supporters across Papua. The arrests came in turn after a bloody December in which the separatist West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB) killed over 20 Indonesian construction workers who were laying the Trans-Papua Highway, perhaps the government’s signature infrastructure project in the region.

The TPNPB was formed in 1973 and has since clashed regularly with Indonesian security forces, resulting in deaths on both sides of the conflict. The group has admitted to using child soldiers – a war crime under international law – but earlier this year vowed to end the practice.

“The security forces are acting as if they are above the law. They act as if West Papuans don’t have any dignity.”

Veronica Koman, lawyer

Veronica Koman, an Indonesian lawyer who represented the KNPB’s Arwakion during his trial, said “we have to make a clear distinction between [the TPNPB] and the non-violent groups such as the KNPB.”

Koman believes the KNPB has been targeted by Indonesian police because of its influence.

“They are the strongest, largest grassroots group in West Papua, that’s why they have become the most persecuted group in West Papua.” she told Southeast Asia Globe in a call. She said that the KNPB is not aligned with the TPNPB.

Koman hit out at the raid on the headquarters, saying it was “beyond my level of comprehension”.

“How could a 1,000-year-old cooking feast – older than Indonesia itself – be now seen as treasonous?” she asked.

A spokesman for the Papua regional police, Suryadi Diaz, told local media at the time that they were simply taking back the building which they had given to the local government and that the KNPB had been using.

Koman is now taking legal action against the police over the raid.

“It’s because the security forces are acting as if they are above the law,” she said. “They act as if West Papuans don’t have any dignity.”

Koman and Arwakion’s struggles are but fragments of the complex puzzle that makes up Papua’s fraught recent history.

The root of the problem

Papua is a former Dutch colony that by 1961 was gearing up for independence as the colonists headed home. The mostly Melanesian people of Papua settled on a flag, a national anthem and set up the New Guinea Council, meant as a precursor to an established government.

But Indonesia, led by its first President, Sukarno, had other ideas. It moved on the territory and claimed it as its own, leading in 1962 to the New York Agreement, negotiated over the heads of Papuans and between Indonesia and the Netherlands.

The deal temporarily transferred control of Papua to Indonesia with the proviso that a referendum would give the indigenous population the final say on their destiny.

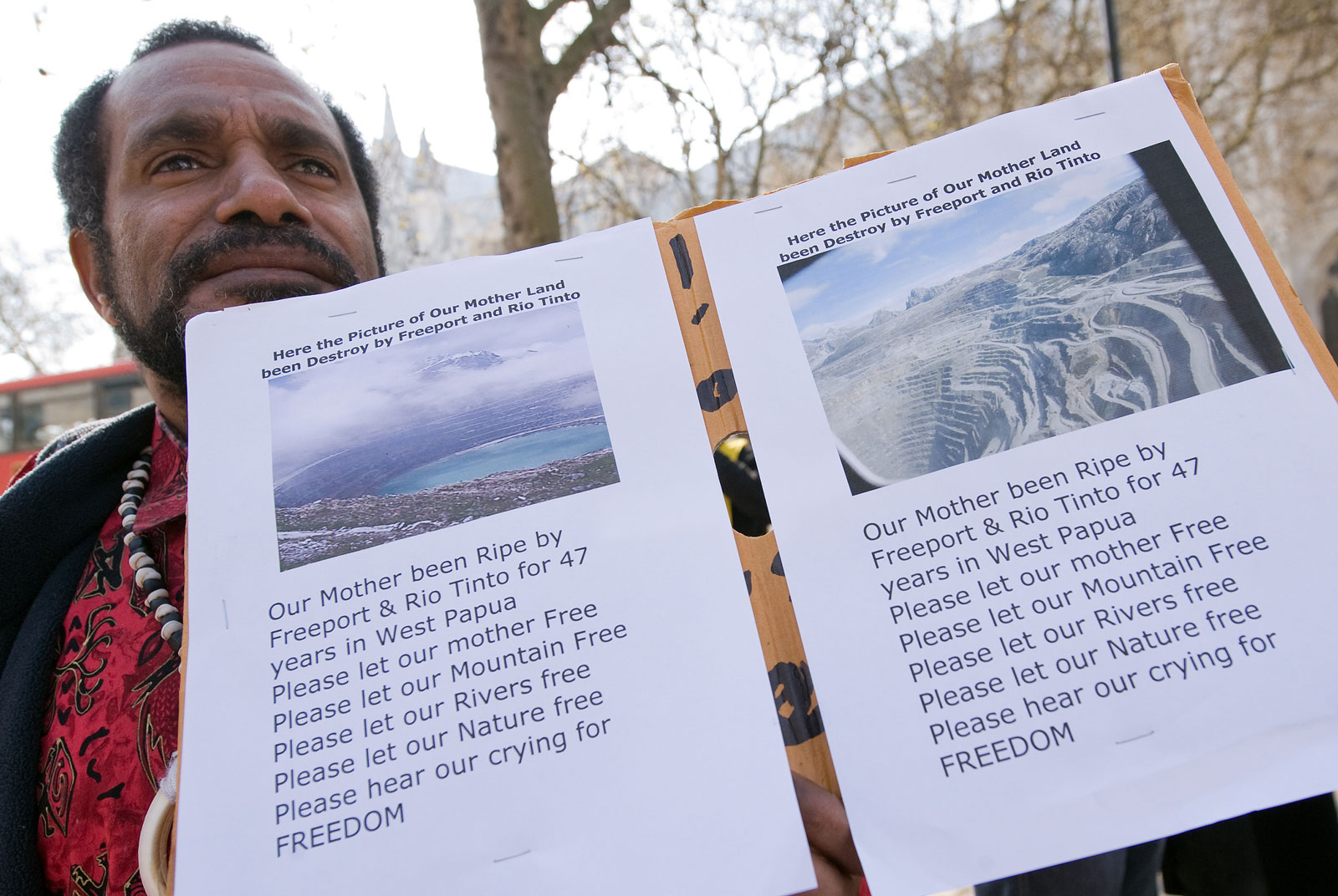

In 1967, two years before that referendum was held, Indonesia signed a deal with US mining company Freeport McMoran to mine copper and gold in the region. In 1969 the “Act of Free Choice” cemented Indonesia’s control of the region with the vote approved by the UN.

The Act of Free Choice “once and for all reaffirmed Papua is an irrevocable part of Indonesia”

Aloysius Selwas Taborat

Vanuatu, which gained independence in 1980, is one of the few UN member-states to publicly question the vote’s legality.

Foreign minister Ralph Regenvanu believes that the world had other considerations at the time of the “Act of Free Choice” – priorities beyond Papuan rights.

“The problem of the time was that it was the height of the Cold War. Indonesia was the ally that the US wanted to cultivate and so based on that, all other concerns are brushed aside,” he told Southeast Asia Globe.

Regenvanu said the situation was similar to Indonesia’s occupation of Timor-Leste, which, after a quarter-century struggle, gained independence in 2002.

When Vanuatu sought to raise support for Papua at the UN last year, Indonesia’s response was dismissive and blunt. Jakarta’s representative, Aloysius Selwas Taborat, said that Papuans had “once and for all reaffirmed Papua is an irrevocable part of Indonesia,” referring to the 1969 Act of Free Choice and lambasting the nation as “clueless”.

In the decades that followed the referendum, reports have surfaced of human rights abuses against the indigenous population by Indonesian security forces, including beatings, torture and extrajudicial killings.

A 2017 report by Amnesty International documented 69 cases of suspected unlawful killings by Indonesian security forces between 2010 and 2018. Added to this are reports of widespread environmental destruction and illegal land grabs.

The Indonesian government has repeatedly denied human rights abuses are taking place in the region. Southeast Asia Globe reached out to various ministries for comment but received no reply.

Verifying illegal activity has long been challenging in Papua, in large part due to a ban on foreign journalists and rights activists entering the region. In January, Indonesian President Joko Widodo invited the UN Human Rights Commissioner to Papua, though this visit has not yet taken place.

Ruth Ogetay is a Papuan who works for the Pantau Foundation, which trains journalists in Indonesia.

She said that the government’s ban on foreign media is a typical tactic of the Indonesian government.

“The rigour and reach of the [media] restrictions, in Papua as well as elsewhere in Indonesia, have varied with political developments in the country, [but] Papua has been deemed off-limits to journalists more often than almost any other region.”

Ogetay was based in Papua from 2015 to 2017, but returned to Jakarta because she didn’t feel safe. She said one day four soldiers showed up on her doorstep, demanding to know the whereabouts of Papuan activists. After this, the military followed her wherever she walked.

“They are monitoring every Papuan people because we want to be free,” she said.

The provinces of Papua and West Papua have the highest poverty rates in Indonesia, while Papua has the country’s lowest life expectancy and the highest child and maternal mortality rates.

Despite this, both provinces are staggeringly rich in natural resources. In 2018, Indonesia bought a majority stake in Papua’s Grasberg mine, one of the biggest gold mines and the third largest copper mine in the world, with reserves worth an estimated $100 billion.

Fadjar Shouten-Korwa, chair of the board of International Lawyers for West Papua, thinks this natural wealth is the reason that the Indonesia government has never countenanced granting independence to Papua.

“I think the root of the problem is the fact that in West Papua, there are a lot of trade interests,” she said.

But in 2014 Papua’s independence struggle changed drastically. A political group known as the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) brought several independence groups under one umbrella, promising to achieve self-determination for the region.

Unity is key

The ULMWP united Papua’s three main independence movements, including the National Parliament of West Papua, which incorporates the KNPB.

Its goal, according to the group’s international spokesman Jacob Rumbiak, is simple.

“ULMWP’s agenda for five years’ time is to educate our people to understand how to establish a legal nation state,” he said.

“Second, unity is the key. When you want independence, you need unity. We also must be united in our agenda,” he said.

Rumbiak likes to break topics down by numbers. While speaking, he repeatedly maps his points in orderly lists.

For him, the ULMWP is a chance to right the past mistakes of Papua’s independence movements.

“West Papua understands that we failed because for a long time we only struggle in military wings,” he said.

The ULMWP is different, he said. It will concentrate on four wings; politics, military, intelligence and diplomacy.

But to achieve independence, the ULMWP, according to Rumbiak, will not negotiate on Indonesian terms.

“We only want to use the UN mechanism because West Papua was transferred by the UN to Indonesia, and we want an international third party to hear what exactly West Papua wants,” Rumbiak said.

UN recognition requires the approval of nine of the Security Council’s 15 members to approve, including all five permanent members, while two-thirds of the 193 UN member-states must vote in favour.

Rumbiak and ULMWP are teaching the population about how the territory can gain UN recognition and about how to understand Papuan territory based on geography, as though Papua is made up of two provinces, there is some confusion around the extent of the territory claimed by independence supporters.

But territory is just one element, Rumbiak said. “Second is people, which we have. And third is government.”

“We [are] trying to shape up something, not copy from overseas, but we try to do our own,” Rumbiak said. “It comes from peace, not anger.”

He believes that if the group can gain support from more UN member-states, and particularly neighbouring Melanesian countries, then Indonesia will have no choice but to acknowledge Papua’s right to independence.

“We believe ULMWP will solve independence peacefully with UN mechanism,” Rumbiak said.

The Pacific Islands Forum, a regional body involving Melanesian countries as well as Australia and New Zealand, is meeting this weekend in Vanuatu, with West Papua likely to be discussed.

While the ULMWP’s far-reaching objectives mark it out as an important player in Papua’s independence movement, it is not the only group with such ambitions.

In April, a group of 15 mostly Papuan lawyers known as the Coalition of Lawyers for Truth and Justice of West Papuan People submitted an application to the Indonesian constitutional court challenging the legality of the 1969 referendum.

“In that specific law, it is stated that the ‘Act of Free Choice’ was properly undertaken and the people in Papua unanimously agreed to be a part of the Republic of Indonesia. So, that’s what we challenge,” Agus Sumule, a spokesman for the group, told Southeast Asia Globe.

Two hearings have been held and the group is expecting a third later this month.

For Sumule, it is about more than winning or losing.

“I personally know that by taking this to the court it will become a wake up call to many people in Indonesia,” Sumule said.

And according to Koman, the lawyer representing the KNPB, calls for Papua’s independence are getting louder.

“The movement inside Indonesia and West Papua and the international community as well, it’s only getting bigger,” she said, citing the example of the Indonesian People’s Front for West Papua, a group established in 2016 that is one of the few non-Papuan groups in Indonesia that campaigns for the territory’s independence.

But even as support for independence swells, the Indonesian government is taking steps to tighten its grip on the region.

Jokowi’s Papua

On being elected President in 2014, Widodo – commonly referred to as Jokowi – promised to develop eastern Indonesia’s economy through infrastructure projects. He has devoted a lot of attention to Papua, his most-visited region as president, outside of Java. After his re-election in April he vowed to continue investing in infrastructure across eastern Indonesia, including the Trans-Papua highway, which has been attacked by Papuan rebels.

Sumule acknowledged the president’s efforts, saying “I would be a liar if I said nothing has improved”.

“We understand that he has put in more money, especially for infrastructure and development. He came to Papua and really showed an interest.”

In 2016 Widodo lowered fuel prices in the poverty-stricken region in a bid to make transport more accessible.

However, Sumule was scathing of Widodo’s attempts to improve living standards for Papuans, suggesting that political issues were being ignored.

“When you talk about other issues like human rights, when you talk about the influx of migration coming to Papua, if you talk about the marginalisation of the people, if you talk about Papuans now being a minority in many regencies… then I think the government – under Jokowi’s leadership – hasn’t done anything at all,” he said.

“Allow the foreign media to come to lift the veil and let the light in so that we can assist to solve the situation or improve the human rights situation of the people living there”

Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu foreign minister

Sumule thinks that the only way the Indonesian government can put allegations of human rights abuses to bed and allay environmental concerns is to permit rights groups and journalists to visit Papua.

Widodo lifted the media ban on the region in May 2015 – the first time this happened since Indonesia took control. However Human Rights Watch’s deputy director of the Asia Division Phelim Kine questioned the scope of this access.

“Despite the rhetoric…the grim reality is journalists are still blocked from reporting there. Violations of media freedom for foreign journalists in Papua, along with visa denial and blacklisting of reporters who challenge the official chokehold on Papua access, continue unabated,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, Vanuatu is pushing Indonesia to honour its promise to allow the UN Human Rights Commissioner to visit the region.

Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s foreign minister, said that the onus was on Indonesia to prove it was upholding human rights – and it could do that, he said, by letting in rights groups and foreign media.

“Allow the foreign media to come to lift the veil and let the light in so that we can assist to solve the situation or improve the human rights situation of the people living there,” he told Southeast Asia Globe.

The anniversary

As the 50th anniversary of the ‘Act of Free Choice’ approaches, there is a quiet-but-persistent belief among independence activists that one day Papuans will have their own independent state.

“Sooner or later, Indonesia must address this conflict with West Papuan people as an equal,” Koman said.

The ULMWP’s Rumbiak also thinks it is just a matter of time.

“The movement is now well organised inside West Papua. So what can Jakarta do?” he said. “They will be under pressure to transfer West Papua to UN and later back to West Papua.”

Many observers from the outside, however, are less sure. With Jokowi pumping ever-more money into building up the region, it appears Jakarta is only going to strengthen its hold on Papua.

Andreas Harsono, a researcher for Human Rights Watch, said it would take a massive political shift internationally for Papua to achieve independence.

“For the time being I don’t see an end to this,” he said, “but I don’t know what will happen in the future.”

He said that the underlying issue is Indonesian discrimination – especially from Java – towards Papuans.

“The best solution is Indonesian… needs to understand that these aboriginal people suffer a lot under our rule,” he said.

For Arwakion, who still has six months left of his sentence, gaining independence will perhaps require divine intervention.

“God knows whether or not Papua will become independent during my lifetime,” he said.

“[But] God has bestowed me this quest for independence and I am working [on it] with all my heart.”