Editor’s note: In 2018, Khmer Rouge ringleaders Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were finally found guilty of committing genocide – though not of the almost two million Cambodians killed by the regime, but the Kingdom’s ethnic Cham and Vietnamese minorities. Since then, though, the trial has stalled, caught in a gridlock with the local and international judges split over whether to proceed against lower-level members of the regime. But for many Cambodians who watched the once-untouchable architects of the nation’s ruin dragged from their lavish homes to answer for their crimes, the Khmer Rouge Tribunal has been a way for countless victims of the regime to see some small justice done. Now, for World Day for International Justice, we look back at our print archives from February 2008 to chart the court’s messy beginnings.

Cambodians can today see a light at the end of a long, dark and sorrowful tunnel. The trials of Khmer Rouge leaders at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal (KRT) have finally arrived after a three-decade long wait.

Once-shadowy figures responsible for the deaths of millions of others through overwork, starvation and forced migration will finally face justice when the UN-backed Khmer Rouge tribunal, officially called the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), begins long-awaited trials of the regime’s leaders this year.

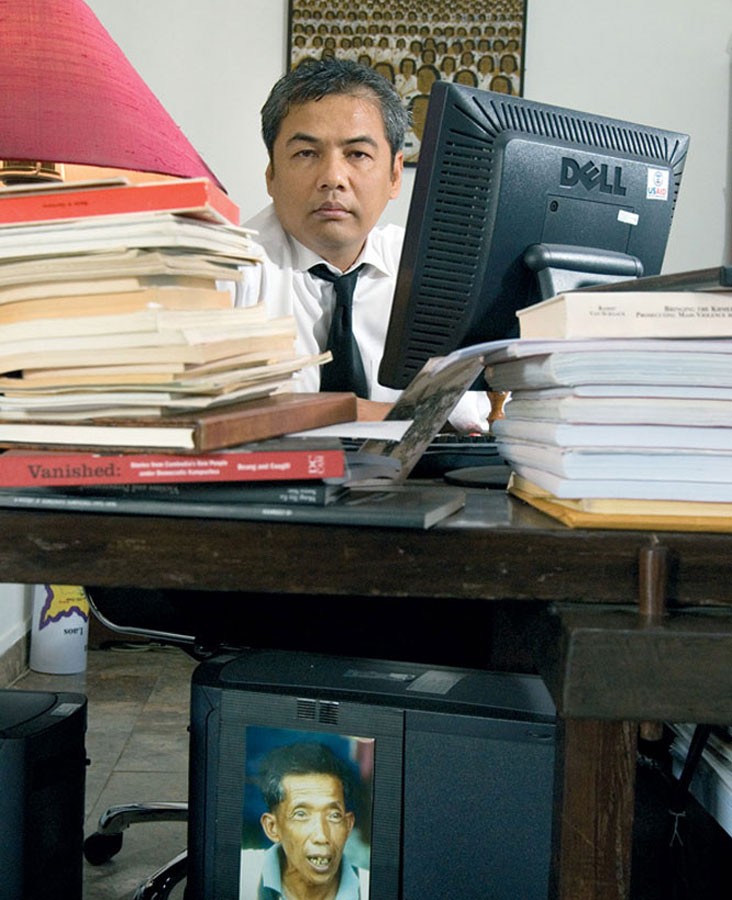

While the Khmer Rouge era should not be ignored or forgotten, the trials will give Cambodia the chance to address and maybe even overcome the legacies of its tragic and traumatic past, according to Youk Chhang, whose Documentation Centre of Cambodia (DC-Cam) has played a crucial role in collecting millions of Khmer Rouge records which will be used as evidence in the trials.

The young generation in Cambodia today are the children of survivors who have been traumatised and suffered under the Khmer Rouge. So it is unfair to say that they do not care

DC-Cam director Youk Chhang

“The tribunal will help the majority of people who are interested in prosecution and is an important foundation for forgiveness, and like it or not it is part of Cambodia’s future,” Chhang says.

“Cambodia is known to the world as the country of the killing fields, and the temples of Angkor Wat – you know Angkor and Angkar – one from heaven one from hell. We will make this horrible history become a piece of education to ourselves and also to the world,” says Chhang, whose work could see some of the Khmer Rouge’s methodology turned against itself in court as its leaders are confronted with evidence based on the kind of meticulous documentation that has long been a hallmark of totalitarianism.

It can often seem to outsiders that Cambodians are indifferent to their living history – that they have put up a wall between themselves and the unspeakable horrors of the not-too-distant past.

Chhang believes that Cambodians are not indifferent to the past, however. “The young generation in Cambodia today are the children of survivors who have been traumatised and suffered under the Khmer Rouge. So it is unfair to say that they do not care,” he says.

“With survivors there are many parts of the healing process, and while the tribunal is not going to please everybody, a lot of people are happy about it. Right now the tribunal is one of the most transparent and widely-discussed subjects in the country. The people have been given freedom of expression and are reclaiming their history,” he says – no small thing in a country with a history of formal and informal restrictions on freedom of speech.

“People can now talk about the King, the prime minister, the accused openly, without fear and intimidation. And in turn the King and prime minister also talk about this – everybody is talking about it. Just ten years ago the Cambodian people were afraid to even begin broaching the subject, because it was a political issue and security was still at the forefront of everybody’s minds,” Chhang explains.

“Now it is free and it is street talk. And as is their right some people are even saying: ‘Enough! I am done with this, I am finished and this is my closure.’ And though we can prompt them to talk, it is done for them, they are free.”

Freeing the country from the past has invariably meant ending the freedoms of its former oppressors. The arrests of former Khmer Rouge leaders – such as foreign minister Ieng Sary and head of state Khieu Samphan – has shattered the auras of invincibility and invulnerability that once surrounded the Khmer Rouge leadership.

Previously untouchable elites, whose lives were of soap opera opulence, have been humbled in the public mind after being seen arrested and awaiting trial

Revenge, much like the portrayal of luxury lifestyles, is another soap opera staple, but despite leading an organisation founded to create a permanent record of Khmer Rouge’s crimes, Youk Chhang bears no inclination toward revenge – even though he was imprisoned by a regime that killed several family members.

“As a person you don’t look at former Khmer Rouge cadres as tigers or crocodiles, these are people, when you look at them, you can see in their eyes that they simply lost their humanity and will do anything to get it back,” he says, explaining why even Khmer Rouge cadres are happy to tell their story to him.

The closed doors of the mind are now opening, Chhang says, and offering the former Khmer Rouge killers a chance to tell the truth about the regime maybe means a belated chance to clear a conscience or hope for forgiveness.

Getting people to talk is an indispensable aspect of post-regime healing, Chhang says. “I have told the UN (which backs the KRT) that even if one person refused to speak to me I would refuse to support the tribunal, not even one person ever has; because during that time everyone in Cambodia lost their self-respect, lost their identity, lost their humanity. By talking about their past they often feel they can gain some of this back.”

To Chhang, talking about the Khmer Rouge – and the tribunal – can make Cambodians feel whole, even human, once again, helping bypass the relatively recent horrors and reconnect with ancient Khmer glories.

“You know as children we were told Angkor Wat was made by the gods in gold, but now we can all go and see it is just made of beautiful stone. Just as this remarkable achievement was made simply by man, so were the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge simply the folly of man.”

While some survivors will always demand vengeance for those atrocities, Chhang concedes, he hopes all the same that others will be happy to get a day in court and see the regime’s leaders face justice.

One man who could not be blamed for seeking vengeance is Bou Meng. Shackled by the ankles to fellow prisoners in what become known as the regime’s most notorious death camp – the S-21 or Toul Sleng detention centre – his days and nights echoed with the screams of the tortured, and drawing breath meant imbibing the smells of faeces, urine and blood, detritus of the nail-pulling and electric shock and sleep deprivation chambers from where the damned were taken to be executed, often by a thudding blow to the back of the head while facing down into a freshly-dug grave.

I was tortured two times a day. They would beat me until I fainted…They used electric wires, and a long rope to whip me

Khmer Rouge survivor Bou Meng

Bou Meng had been arrested a few weeks earlier with his young wife Neary. Both were later accused of being enemies of the revolution, a virtual death sentence, but at the time the young couple believed they were being taken to teach at an art school, having no idea of the gravity of the charges they faced.

Dragged from a life of near starvation in a communist farming cooperative, the couple were subjected to the unrelenting and inescapable terrors of the regime’s torture centre.

Upon arriving at the centre, their jailers – meticulous as ever – took mugshots and added the couple’s details to the growing prisoner list.

It was last Bou Meng ever saw of his wife.

“I was tortured two times a day. Five or six Khmer Rouge guards come to beat me almost everyday. They would beat me until I fainted…They used electric wires, and a long rope to whip me,” he says.

Short in stature but of noble bearing, Bou Meng, now 66, was saved by his artistic ability – a tragic irony as the same ability was the reason why hundreds of others were murdered by the regime.

Before the Khmer Rouge victory he had painted the walls of wats (temples) with flowing Buddhist murals.

But it was a much different time when years later he saw the regime’s teenage jailers kill an elderly prisoner by jumping repeatedly on a defenceless old man’s chest.

Later the same boy killers asked if any of the detainees could paint Pol Pot.

Feebly, even foolhardily, Bou Meng raised a shaking hand.

This was in 1977, halfway through the Khmer Rouge’s reign of terror. It was time, as was the case with all dictatorships, to forge a cult of personality around the leader, meaning a need for statues and paintings of the man himself, the despot Pol Pot.

But most artists – bourgeois and Westernised and decadent, as the regime rhetoric went – had been executed, so the task was left to prisoners like Bou Meng to draw up some Pol Pot iconography.

“The KR first let me try to paint a picture of Lenin in front of them. They told me that I painted very well and asked me to paint a picture of Pol Pot. At that time in 1978, I did not know who Pol Pot was. They gave me some painting materials, asking me how long would I spend on painting one picture of the leader. I told them I needed three months for one picture. They said, ‘Ok you can paint it now.’”

“I painted every hair on his head very carefully,” he adds, in what must be one of the most ironic understatements ever made recalling Khmer Rouge rule.

During his long Khmer Rouge purgatory Bou Meng endured horrendous tortures – most of his teeth were smashed out, he has permanent hearing loss from blows to his head and his back has deep scars from bamboo canes – but he still smiles each day.

He can accept what he endured at the hands of his tormentors but finds it hard to forgive what must have been the gruesome torture and execution of his beloved Neary.

He uses the word revenge, but not in the sense of physical eye-for-an-eye retribution.

“I want revenge most of all for my Neary and the children that I lost under the regime, especially. But, my revenge will be peaceful and through the ECCC,” he says.

“I trust the ECCC as it has been joined by international judges. If there were no UN intervention in the trial, I wouldn’t believe that the court can bring justice for all Cambodian people and me. I need all the KR leaders to be brought before the court soon for justice because I am one among the many victims that suffered from the terror regime.”

For many Westerners it is inconceivable that you could live alongside someone who worked for a genocidal regime that killed your wife, but Bou Meng counts as a neighbour one Him Huy, a clerk at the Toul Sleng detention centre, who recorded many of the so-called confessions beaten out of bewildered and terrified detainees.

On the first day of his detention, Huy forced Bou Meng, a slight man not much more than 5 feet tall, to carry him on his back up a flight of stairs. A bizarre display of hierarchy and power under the regime, maybe, but not one worth bearing a grudge over, all things considered.

“I have met him [Him Huy] several times since. First in 2003 or 2004 when we were at the DC-Cam. I asked him if he knew where my wife was, ‘I don’t know’ he replied. I asked him if he killed my wife, he said, ‘No, I did not know anything about your wife. We should forget the past and think of today’.”

Obviously and unavoidably traumatised by ordeal, Bou Meng hopes the court will at least provide some outlet for his grief.

“I don’t want to think about it. But I feel traumatism, as I am very quickly scared at the slightest thing and I cannot hear everything clearly. I often dream the victim’s souls come to my mind and ask me to take revenge against the KR for them. I see them surrounding my house. Some of them are bleeding, some others look very sad or cry, they are all very thin.”

Some nights, he says, he dreams of his long-lost wife and the small gifts they gave each other and the many precious moments they shared when she was alive.

Bou Meng has twice taken the rickety ferry up the Mekong to visited the dramatic courthouse building built outside Phnom Penh to try the former Khmer Rouge leaders. He sketches courtroom scenes, his artwork interrupted by reporters and researchers who want to know how it feels to see the murderers of a young wife face justice after thirty years.

But not all survivors are content with mere judicial retribution. Res Halimas, a 57 year-old Cham – a Muslim community which suffered horrendously under the Khmer Rouge – cannot contain her anger.

“To satisfy me, who has suffered terribly from the regime, I would take my revenge by using physical violence. However, I am very happy to see the KR leaders come to the trial and hope justice and the truth will come in the near future,” she says.

Res Halimas lost her parents and in-laws during the Khmer Rouge era, with ten more relatives disappearing as well.

Her family lived in Phnom Penh’s Chrang Chamres district, where there are three big mosques and many other small ones.

“The KR strongly abused the rights of the Chams. I remember that one lunchtime, the KR cooked rice porridge mixed with pork. The KR knew that we were Muslim, but they still made us eat that porridge. We had to close our minds and unwillingly eat it to avoid being killed,” she says.

Perhaps one day her parents had enough and refused to give in, for that day, she saw the Khmer Rouge lead her parents off to their execution.

“Later I saw my parents’ clothes in the field. I felt very empty and sad.”

The Khmer Rouge was finally driven from power by the invading Vietnamese army, but to this day she asks why no foreign country came to help Cambodia earlier and prevent the murder of around a quarter of the population.

Helen Jarvis, the KRT’s public affairs officer, has made it her personal mission to ensure the tribunal takes place because she feels that people like Res Halimas deserve justice.

She first arrived in Cambodia to help rebuild the National Library, which the Khmer Rouge gutted and turned into a ground for pig-keepers.

“I’ve been concerned with this issue [the KRT] since the late 1980s. I began documenting the crimes in 1994, and in 1999 I began working with the Cambodian government. I’ve seen the process from a closer perspective than most and believe it simply must happen, they [the Khmer Rouge] must be held accountable for their crimes,” she says.

For Res Halimas, the arrests of the five suspects now in custody – Toul Sleng chief Khaing Kek Ieu (Duch), former acting president Nuon Chea (Brother Number 2), former head of state Khieu Samphan, former minister of social affairs Ieng Thirith and former foreign minister Ieng Sary – have given her some relief.

“The arrests were very professional and conducted without any incident or difficulty; they really take the court to a new level and lead us into the reality of the judicial process after all this time,” she says.

She disputes the view that Cambodians and the international community have different expectations from the tribunal.

“I don’t think you can generalise shades of opinion or shades of enthusiasm,” she says. “There are some levels of disbelief and skepticism on both sides but mostly Cambodians have a pressing concern that their suffering is going to be forgotten.”

The KRT had a rough start when negotiations between the government and the United Nations often broke down, something Res Halimas believes is secondary to the achievement of getting the tribunal up and running.

“Clearly the negotiations were protracted and the search for funds was difficult, but we have now achieved a great deal and the general population wants it. But it’s not going to be easy – we don’t wish to rewrite history and there are deep psychological scars that will no doubt be stirred”

The KRT’s forum has visited most provinces in Cambodia and most people seem keen for the hearings to proceed, after so many years of waiting. For Res Halimas, it seems Cambodians are taking a keen interest in the tribunal – echoing Youk Chhang’s view that the trials have become “street talk”.

“There’s no doubt it’s had an important impact on the nation, it’s on the radio, the TV, there are bumper stickers,” she says.

“In all the visits to the countryside I’ve never had a single negative reaction, the people are thirsty for information.”

This article has been edited for clarity.