Hate speech isn’t a new phenomenon in Myanmar. But it has intensified with the advent of social media, smartphones and affordable SIM cards.

“I’ve been called a kalar-lover [and] had my address, my ID card, ethnicity, native city, religion and address leaked,” said youth activist Khin Sandar, describing her experiences on the receiving end of hate speech on Facebook. She’s had to deal with the panic of reporting daily posts of abuse on the site that insult her religion, disclose her personal identity and threaten her safety.

Memes calling Muslims rats or dogs, or using the word kalar – a common racist slur against Muslims and Indians – are just some of the examples of hate speech that continue to be shared on Facebook, despite the scrutiny of activists and promises by the platform. Personal attacks like those Khin Sandar experiences are still slipping by Facebook’s monitoring team, several sources have confirmed to Southeast Asia Globe.

Facebook defines hate speech in its Community Standards as “a direct attack on people based on protected characteristics – race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, sex, gender, gender identity, and serious disability or disease.” But, while its standards are clear, its detection of breaches falls short, say critics.

The other major problem is that social media is a new information delivery technology with a steep learning curve. In Myanmar, Facebook is so dominant that it’s seen as the internet itself, said one activist. Most Myanmar people use Facebook as a search browser and their primary news source. Internet literacy is extremely low in the country, as a new generation leapfrogs from a time under the military regime when only the elite could afford to buy a SIM card that cost up to an astounding $1,500, to a new generation of smartphone users who can now buy SIMs for just $2 each.

Myanmar is not alone. As one Sri Lankan analyst told the Guardian, while Sri Lanka enjoys high literacy, it suffers from a lack of information literacy: “It means the population can read and write but tends to immediately believe and uncritically respond to that which they see on social media.”

At a peace march in Yangon in May, around 300 activists held signs with doves on them as they called for an end to all military skirmishes in the country between government forces and ethnic minorities like the Kachin in northern Myanmar. The demonstration was shut down after some civilian Buddhist nationalists showed up and started attacking protesters as the police looked on. When police finally decided to intervene, it was to arrest the protesters who were under attack.

Khin Sandar was one of those activists. She pulled up a screenshot of a Facebook post showing a photo of her being arrested by police at the protest. The Burmese comment that went with it translated roughly to: “These people earn dollars and are creating unrest by associating with rebels and kalar.” The post was shared again and again, often with comments calling for violence and even death threats against Khin Sandar.

The population can read and write but tends to immediately believe and uncritically respond to that which they see on social media

Khin Sandar said she reported the post to Facebook as hate speech. Twenty-four hours after the protest, she checked her phone to find that the post was still up – and was clocking hundreds of shares. She was scared, so she alerted family and friends.

“I was at risk and my friends were trying to help me,” she said. “Friends were reporting the post through their accounts and others were trying to email Facebook administrators directly to alert them to this serious case.”

It took 48 hours for Facebook to review, respond and delete the post. By then, it had been shared nearly 1,900 times. She felt helpless.

Critics say Facebook’s slow response time to hate speech increases the danger to those at which it’s directed.

Although Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg pledged to commit to a 24-hour review and removal of hate speech at the landmark US Senate inquiry in April, Myanmar activists say the average response time is closer to 48 hours.

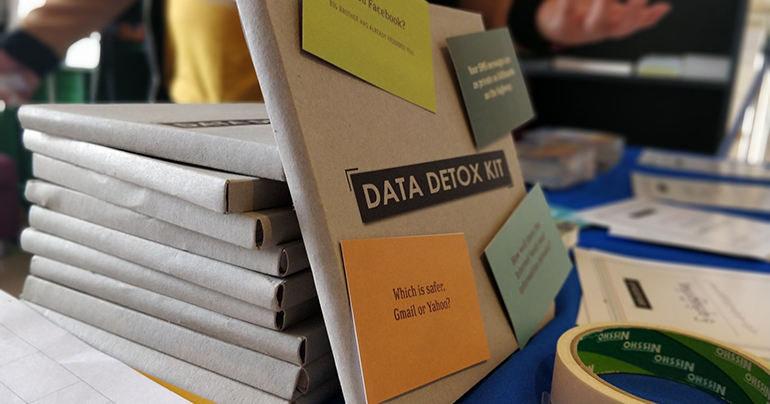

“The problem of hate speech has not gone away,” said Htaike Htaike of the Yangon-based Myanmar ICT for Development Organisation (Mido), a group that teaches internet literacy and monitors hate speech. Mido launched its Safe Online Space (SOS) curriculum in 2016 to teach people the basics of social media and the internet, how to report hate speech on Facebook and how to identify hearsay versus actual news. Through its “training of trainers”, Mido is developing a network of people to pass on this knowledge across Myanmar.

Htaike brought out her laptop and showed the data Myanmar activists have been collecting of serious hate speech posts that have been reported to Facebook. Next to each post was a column showing how many hours it took for it to be removed. The most common wait time was 48 hours. But Htaike said these few posts represented a tiny fraction of the thousands of hate-filled posts Mido has tracked.

This slow response time has not improved since March, when the UN called the social media giant a “beast” for its alleged role in fuelling the violence against the Rohingya – in part by allowing hate-speech posts to be shared online.

These Facebook posts included lists of well-known activists and Muslim community leaders who were vocal on the Rohingya issue, with links to their Facebook accounts. Some posts called for activists to be assassinated. One post depicted the purported corpse of a Rakhine Buddhist woman with ripped clothes lying in the grass, with the suggestion that she had been raped and murdered by Muslim men – an old story that led to deadly violence in Rakhine State in 2012.

Two chain messages – one to incite violence against the Muslim community and a separate message mirroring the words of violence against the Buddhist community – were shared hundreds of thousands of times leading up to 9 September last year. They ordered people to take up arms, warned of jihad and encouraged an anti-kalar movement.

Since the crisis that led to over 700,000 Rohingya fleeing from Rakhine State to Bangladesh – described as ethnic cleansing by the UN – hate speech only continues to escalate.

“We know we’ve been too slow to respond to the developing situation in Myanmar,” admitted David Caragliano, a Facebook content policy manager, during the company’s first visit to Myanmar, in May.

When they brought in the blanket ban of the word kalar, it became a joke because it didn’t work

A team of five Facebook staff visited the country for one week for a whirlwind of meetings with Myanmar-based civil society organisations, activists and the government.

The Facebook rep insisted the company is improving as a hate-speech watchdog. Referring to the same protest in Yangon, Caragliano vaguely suggested they were able to respond to some reports during the protests within 24 hours: “We removed numerous pieces of threatening content towards activists within three hours and a video depicting graphic violence.”

These examples are not enough, said Burmese activists.

“Two out of how many hate-speech posts?” asked Ei Myat Noe Khin of the Yangon-based tech accelerator Phandeeyar, which helped Facebook translate its Burmese-language community standards. Despite her group’s repeated requests, she said Facebook had not shared any information or metrics with Myanmar groups to show how it is monitoring posts – or how many posts it had removed and how quickly.

Herein lies the problem at the heart of the hate: no evidence or transparency of country-specific Facebook reports. So activists from Sri Lanka, Vietnam, India, Syria, Ethiopia and Myanmar formed the Global South coalition in May to hold Facebook accountable for failing to put adequate protections in place.

Wirathu, Myanmar’s most notorious hardline Buddhist nationalist monk – who has been charged with inciting anti-Muslim riots – finally had his Facebook account suspended in late January this year after he had been repeatedly caught breaching Facebook’s community standards with hate-filled posts.

Yet Htaike Htaike said monitoring by Mido has found that bad actors like Wirathu are still active on the platform, sometimes using fake names. And even if Wirathu and his ilk are locked out, they have plenty of followers to carry their hate torches high. Wirathu’s hardline nationalist group, the Patriotic Association of Myanmar, abbreviated in Burmese as Ma Ba Tha, thrives on Facebook pages and in multiple groups.

Reporting and deleting of posts is not enough, say activists – better detection is sorely needed. Facebook’s Caragliano said the platform is getting tougher in its approach to hate speech by implementing systems to “proactively detect this kind of content”, but Myanmar cybersecurity groups say they are still seeing these blacklisted figures online.

Caragliano admitted it is hard for artificial intelligence to identify hate speech with the same precision with which the platform identifies nudity, terrorist propaganda and spam. In Myanmar, the challenge for Facebook to build systems that detect hate speech in the Burmese script-based Zawgyi One and unicode fonts isn’t as simple as taking down posts with key words.

When Facebook suddenly banned the slur kalar last year, Htaike Htaike said it was a Band-Aid solution: “When they brought in the blanket ban of the word kalar, it became a joke because it didn’t work.” That ban didn’t establish a process, Htaike explained. It was a shortsighted decision that meant phrases like kalar page (lentil beans) were also suddenly taken down. Facebook said its review system now considers context.

Another roadblock is detecting hate speech on closed pages and in private messages. One improvement Facebook has made is to provide a reporting button in Messenger, but group members of pages are not likely to report hate speech if they are in a group that aligns with their beliefs. To combat this, Facebook said it has “updated our guidelines and now have more nuanced rules that help us take down abusive groups that have bad intent”. But Facebook hasn’t shared any data to back this claim.

Activists say that instead of these narrow policies that target words, Facebook should invest more in a language team in the region that can react in real time.

“We are still doing the reporting, [but] they can’t keep relying on us,” said Htaike. “They ask us for data, which of course we will provide, but for longterm data collecting, they need a better team.”

She stressed that the job of monitoring hate speech is extremely risky in Myanmar: “I am in a dilemma about having a Facebook in-country team as I am very concerned about security aspects, because even community civil society organisations like us are harassed and cyber-bullied just for having a relationship with Facebook.” Her group Mido has been harassed when something goes wrong, as with the “lentil beans” fiasco.

But anyone Facebook hires to do this job should be based in Myanmar, said Htaike, who is concerned that the site recently advertised a position for a Burmese analyst to join its team, but that that person would need to move to Dublin. “They at least need to be in the same time zone,” she said.

Facebook said it is hiring three new people a week, at the time of this writing, to work on Myanmar hate-speech reviews, but would not reveal the size of its Myanmar team.

Caragliano would say only that “we have added dozens more Myanmar-language reviewers and we hope to double that number by the end of this year.”

In July, Facebook announced that it had hired the San Francisco-based nonprofit Business for Social Responsibility to conduct a human rights impact assessment, which Myanmar activists and the Global South welcome. Yet questions remain unanswered about what exactly the report will reveal or how it could help things on the ground.

“We are waiting to know what their methodology will be and what they will actually enforce after the assessment,” said Ei Myat Noe Khin of Phandeeyar.

Without solid sustainable improvements from Facebook to tackle the hate-speech problem, the Global South coalition said that online inequality will continue to widen as Facebook expands to capture emerging markets without proper investment in monitoring and protections.

The Global South is blunt in its assessment of the power held by social media in the nations that make up the coalition: “The coalition countries include the world’s largest democracy, the first social media–enabled genocide, state-sponsored troll armies and the devastation of the Syrian war. In each of our countries, Facebook has been weaponised by bad actors against our citizens.”

In its press release announcing the new coalition, Global South accused Facebook of failing to invest in the “basic contextual understanding, local language skills, and human resources needed to provide a duty-of-care for users in sometimes repressive regimes”.

Myanmar activists seem reluctant to put much hope in Facebook’s promises since it hasn’t been able to tackle a problem that first erupted in 2014 in Mandalay, the country’s second largest city. In July that year, an unsubstantiated story circulated online that claimed a Buddhist employee of a tea shop had been raped by her Muslim employers. The resulting riots spun out of control, taking two lives and shattering the calm of a nation taking baby steps into the promises and dangers of the gilded information age.