A recent report rates Southeast Asian electoral integrity the worst in the world, but does it matter?

Southeast Asia is a mixed bag in terms of democracy. From monolithic one-party states through to newly authoritarian regimes, autocratic systems and countries emerging from years of dictatorship, it takes all sorts to make this region.

But even when citizens in Southeast Asian countries are given a ballot paper to mark, studies show that the region is not a shining example of probity at the polling booth.

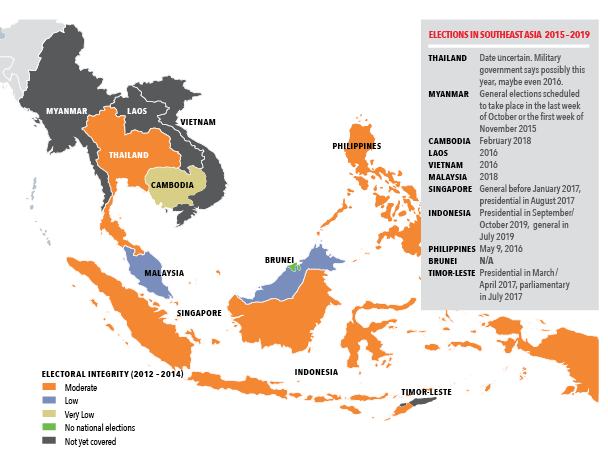

A recent report called Year in Elections, 2014 – the Electoral Integrity Project (EIP)’s global survey of domestic and international election experts – said that Southeast Asia has earned the dubious distinction of being the weakest region in the world in terms of electoral integrity.

According to Max Grömping, a researcher for EIP at the University of Sydney and one of the report’s contributors, “none of the Southeast Asian countries hold elections of ‘high’ integrity”.

Of all the countries in the region, EIP – a joint venture by Harvard and Sydney universities – found that Malaysia and Cambodia “were evaluated well below the global average” across all stages of the electoral cycle.

In Malaysia, Grömping saw the delineation of electoral districts as the largest problem. Rural constituencies – strongholds of the ruling party – contain far fewer voters than urban ones, meaning that although the opposition coalition won the majority of popular votes in the 2013 election, it did not get enough seats to win power. “This meant that rural votes were effectively weighted more than urban ones,” he added.

Over in Cambodia, according to a coalition of Cambodian human rights NGOs in their Joint Report on the Conduct of the 2013 Cambodian Elections, the poll was marred by missing or duplicated voter names and voting by foreign nationals, along with the electoral campaign period’s bias in favour of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party.

One essential component of holding a free and fair election is the selection of independent, impartial and professional election commissioners to run polls. “[It] is not an easy process, but having smart, independent people in place that are sincere with their intent to carry out clean elections goes a long way,” said Ryan D. Whelan, campaign and advocacy coordinator at the Asian Network for Free Elections (Anfrel).

But, some may say, why hold representative elections in the first place? Singapore has prospered without having a structurally independent election authority and with the overwhelming influence of the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) for 50 years now.

That is not the point, however, contends Whelan. “I can show you far more countries that have the authoritarian model that are poorer because of it than you can show me countries that have authoritarianism that are richer because of it,” he said. “In terms of conflict resolution and peaceful transition of power, [free and fair elections] are still the best model we’ve got.”

If a government is elected as a result of a well-run election it will be perceived as legitimate in the eyes of the public, said Pippa Norris, a comparative political scientist at Harvard. Her book Why Electoral Integrity Matters argues that poorly run elections will, by and large, lessen the public’s positive sentiment about the legitimacy of a regime. Legitimacy, she wrote, is important in adding to stability and lessening the likelihood of violent conflict.

Some contend that Singapore is indeed a legitimate democracy, pointing to its regular elections and the fact that opposition parties do take up seats. Others argue that the ruling PAP holds all the cards with its dominance of the media and legal system.

Simon Springer, assistant professor at the University of Victoria, Canada, is sure that there is only one reason elections in the region are held at all: they do not really make a difference.

“There is an expression that says: ‘If elections changed anything, they’d be illegal,’ and I really think that is the mindset that many governments are unfortunately working in across Southeast Asia,” he said. “The only reason that elections are tolerated is because they have very little impact on the ebbs and flows of political power.”

In Grömping’s mind, countries that push for economic liberalisation but keep the brakes on political reform may well be economically successful.

“It is very clear that political liberalisation is not in the interest of any authoritarian ruler. We have seen that an economic liberalisation and capitalist development can work very well without political liberalisation,” he said, singling out Pinochet’s Chile, the Gulf states and China as examples. “At the same time, economic liberalisation is most likely to benefit the already privileged class within a country that already holds political power. Myanmar showcases this nicely.”

Still, Southeast Asian countries continue to go to the polls and, according to the EIP report, there are some brighter democratic spots in the region. Elections in Indonesia and the Philippines – in 2014 and 2010 respectively – resulted in peaceful transfers of power. In Indonesia, the country’s independent electoral commission, the Komisi Pemilihan Umum (KPU), committed to open election data before the 2014 vote. Subsequently, in cases where rival politicians both claimed victory, ‘citizen pollsters’ analysing the data quickly identified the losing side. One website, kawalpemilu.org, was able to transcribe and verify 97% of the votes within five days.

Another country making moves is Timor-Leste, which – according to Grömping – appears to be on a “remarkable and fast trajectory towards liberal democracy”. He puts this down to the fact that it scores well on all standard indicators used to measure democratisation. The country has its next elections scheduled for 2017.

In general, there is reason to be cautiously optimistic. As Asean moves towards increased integration, the onus will be for it to speak as one voice and move towards having equal standards. But it will be a slow road, according to Whelan.

“Asean has a lot of good people within the organisation but they face real challenges because so many of their members are nowhere on electoral democracy,” he said. “So there are a lot of challenges to having real change in elections.” This is perhaps most starkly borne out, Whelan said, by the conflicting statements and initiatives – or lack thereof – on democracy produced by whichever country happens to be chairing the bloc at the time.

But it is not elections themselves that guarantee better governance. Other factors come into play, such as the rule of law, the extent of corruption and the competency of state institutions. A government may have been elected freely and fairly, but that does not mean it can necessarily deliver decent roads, schools and hospitals. Better elections will not automatically lead to better governance in Southeast Asia but “it would however lead to better opportunities for accountability and possibly legitimacy of governments”, said Grömping

But, according to Springer, there is a sea change under way. He believes that people are moving away from trust in the traditional electoral model, with pressure instead coming from a grassroots level in an “implicit recognition of the limitations of electoralism”.

“People are increasingly willing to become involved in social movements and public protests to communicate their ideas, find their voice and bring attention to their demands,” he said. “This will put pressure on governments to make real and meaningful change.”