Led by renegade architect Michael Reynolds, Earthship Biotecture is trying to change the way people think about building by repurposing the world’s leftovers. They hope their current project will help rejuvenate a small Philippine village that was ravaged by typhoon Haiyan

By Rubén Cortés and Dene Mullen Photography by Federica Miglio

Michael Reynolds has beeeen called a lunatic, a garbage warrior and “a disgrace to the architectural profession”. His marriage broke down due to his passion for his work. But the creator of Earthship Biotecture hasn’t let such minor mishaps dampen his enthusiasm.

“We’re constantly evolving, but we’re starting to have success at having people replicate – and that’s the idea. We try to make a life for people that doesn’t require diesel fuel and all kinds of sewage being dumped into rivers,” said Reynolds. “Our buildings encounter the environment all over the planet and they help people make a life for themselves in harmony with that environment.”

An earthship is a solar building made of natural and recycled materials including tin cans and old tyres, and provides features such as a comfortable temperature without heating or air-con systems, potable water from rain and snow, clean energy and grey water to grow food. To get a good idea of where the organisation is coming from, Earthship’s mission statement includes its intention to “take small, believable steps towards slowing down and ultimately reversing the negative impact of human development”.

That Reynolds was treated as something of a madman for espousing such ideas in the 1970s is perhaps no surprise. But in today’s more enlightened times, his approach is not written off so easily, especially given that Reynolds ensures that his designs meet the stringent building codes in his native US. Earthships can currently be found from Canada and the Netherlands to Mexico and Georgia, but they might have the greatest impact in Asia. According to the Asia Business Council, every year more than half of the world’s new buildings are constructed in Asia, yet developers rarely implement efficient designs or take into account environmental impact. According to the Asia-Pacific Energy Research Institute, final energy consumption in Asia increased at a rate twice the global average between 1971 and 2004.

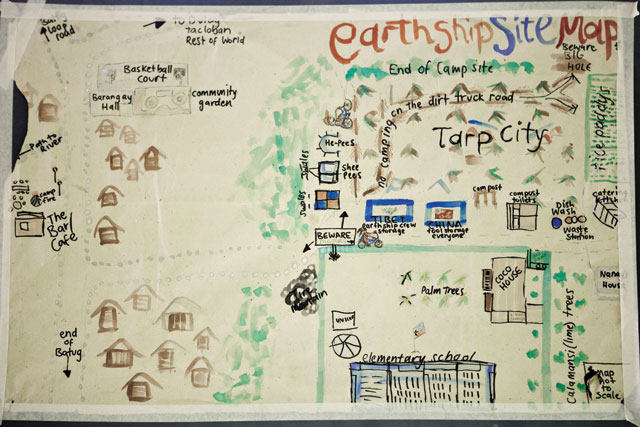

Southeast Asia’s first earthship was built in the Andaman Islands following the 2004 tsunami, and it was another humanitarian disaster that prompted the construction of the organisation’s most recent project. When typhoon Haiyan ripped through the Philippines in November last year, it displaced 660,000 people and devastated many small communities. Among them was Batug, a tiny village on Leyte island, close to Tacloban.

“It’s very important for this place that our building will not get blown away during their typhoon season,” said Phil Basehart, lead builder at Earthship Biotecture. “The locals told us they get about 20 typhoons a year of varying degrees, but the last one… just blew everything away. So we are trying to offer security right here.”

The organisation swept into Batug in February with 50 volunteers and, in a departure from their usual designs, completed the first phase of what has been dubbed the ‘Windship’. It will function as an aerodynamic storm shelter and school building for the community and will be finished in February, when the Earthship team will return to complete the building’s finishes and install the power and water systems.

“Shortly after the typhoon hit I was sat at my kitchen table making sketches on napkins of something that would withstand a typhoon,” remembered Reynolds. “Things fell together and people fell together and we ended up with 50 people here so the structure’s 95% done. It is a fortress against the wind and it’s got some new features because of that wind factor. It looks like something that we’ll be using all over the Middle Earth, 15 degrees north and south of the equator – this is a really good design for the tropics.”

Indeed, there has already been much interest from Philippine government officials in the replication of the Windship throughout the country in the hope of eventually providing a slew of typhoon-resistant, multi-use community buildings. Basehart feels that, in the Windship, the organisation has created not only a model for the Philippines, but one that has been tailored to many of Southeast Asia’s special requirements.

“This building is obviously not trying to get solar energy for heating. Quite the opposite; it’s trying to give shade and create spaces that will cool themselves and stay cool,” he said. “We have to look at cooling design aspects for this region. Just as important though, is to provide simple ways to filter drinking water. The quality of water that people drink is what eventually limits longevity.

“Water quality improves as you contain and treat wastewater so it doesn’t leech down into the water table. I doubt their wells are very deep here in Batug. They might even be hand-dug, so there’s not a lot of earth filtration happening. Therefore containing sewage and providing water filtration is definitely a big point – not just here but in many parts of developing Asia.”

Certain Asian governments are already being forced to import water from neighbouring countries and, according to the Asian Water Development Outlook 2013 report, 37 out of 49 countries assessed in Asia-Pacific have low levels of water security. With almost every social and economic trend indicating continued growth across Southeast Asia, the demand for water, sanitation, housing and affordable energy will continue to rise. This is where Reynolds feels Earthship comes in.

of the Windship’s main rooms. The material ensures the structure has a source of natural light. Photo: Federica Miglio

“The elements are always there. The sun is in Cambodia just like it’s in New Mexico,” he said. “At Earthship, we simply relate to the sun in a different way in each part of the world – we look at all the phenomena and adjust to wherever we are. The designs need to be tweaked but they are all the same concept: Sun and wind make electricity. Biology treats sewage. Water falls from the sky. This happens all over the planet. It’s simple.”

Keep reading:

“Face value” – Vietnam’s unrelenting belief in the power of rhino horn is causing the animals to be mutilated and driven to extinction