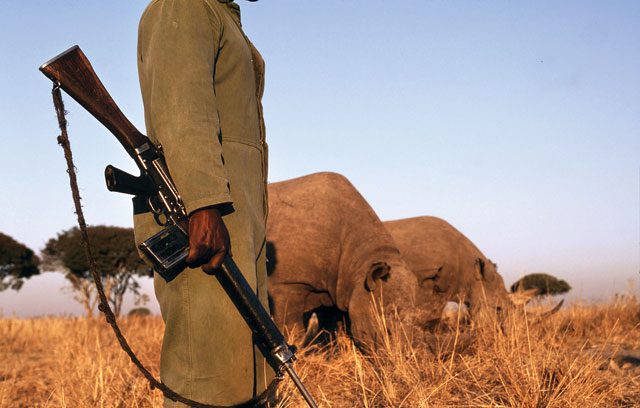

Three shots from a high-calibre rifle ring out across the bushveld. It is about 2am in Kruger National Park, South Africa, and a team of rangers have been hot on the trail of suspected poachers for the past two hours. A helicopter is scrambled and lands a special forces unit in Houtbosch Section. Contact is soon made, and a firefight ensues. Three poachers are apprehended, but one dies at the scene from his wounds. However, he is not the only one fatally wounded.

Nearby, “a white rhino cow was crying pitifully, its horns had been hacked off crudely, it was still alive, its eyes had been gouged out and the spine had been hacked. It could not move but kept trying to lift its head,” said Ken Maggs, chief operations officer of South African National Parks’ anti-poaching initiative. He has seen many horrifying sights, but none quite as bad as this.

Although Vietnam has signed up to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the implementation of it has been very patchy, with Traffic reporting that the market in the country for rhino horn is “growing and very open”. The highest levels of the government seem implicit in the trade, with its effectiveness in curing cancer supposedly originating due to an unnamed government official recovering from the condition. Vietnamese diplomats have also been implicated in the illegal rhino horn trade by the Environmental Investigation Agency, with diplomatic staff serving in Africa allegedly involved with smuggling.

He has seen many horrifying sights, but none quite as bad as this.

In the past few years, poaching has increased exponentially in South Africa, where most of the world’s rhinos now survive. As of September the number of rhinos poached this year stands at 704, compared to 668 for the whole of last year. South Africa estimates that, if the current trend continues, rhino extinction will occur around 2026.

Evidently, current measures to combat the trade are not working. Even as South Africa has tightened regulations, poaching has increased. From a very low level in the mid-1990s, rates increased before the introduction of trophy hunting – which is completely legal – where Vietnamese pay to take part in the hunts and then take the horn.

Poaching dropped after this, only to shoot up with the implementation of Threatened or Protected Species regulations in 2008, which made it very difficult for rhino owners to do anything without a permit and also leaked information to the crime syndicates involved in poaching. Rates rose further in 2009 with the moratorium that stopped internal sales of horn within South Africa. With these ‘legal’ routes closed, the price of horn has increased, leading to a knock-on increase in poaching levels.

Investigations by Traffic, the wildlife trade monitoring network, indicate that Vietnam is now the key country leading demand for rhino horn. This is evidenced in both the final destination of seized shipments and by tracing the trade chain following arrests of crime syndicate members.

Ironically, Vietnam used to have its own rhinoceros population. Back in 1989, a small group of Javan rhinos, the most critically endangered of the five existing species, was discovered in south Vietnam. This led to the creation of Cat Tien National Park about 150km north of Ho Chi Minh City. In April 2010, with the discovery of a rhino carcass, the population was declared extinct – all dung samples collected between 2009 and 2011 were from this animal.

Records of the use of rhino horn in Chinese pharmacopoeia go back at least 1,800 years, with it traditionally used to treat ‘hot’ diseases such as fevers, inflammation and toxicity. By the 7th Century, it was common for the nobility to have cups made from rhino horn due to the prevalence of assassination at the time and the ability of the protein keratin – essentially the same material as your fingernails – to detect poisons.

“Someone figured out that rhino horn drinking vessels were very good at detecting poisons because most poisons were alkaloids and when they were poured into these keratin cups they started to fizz and react,” says Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes, an independent conservation economist, who thinks this historical use may help explain the belief in the healing properties of horn.

Today in Vietnam the use of rhino horn appears segmented but is associated with the rich and famous. Not only is it used in the traditional way, but some people believe it is effective against cancer, and it has also become a party drug – used as a hangover cure. “Rhino horn is often given as a gift to curry favour with business relations and political officials. The key driver from our research is the emotional one rather than the functional,” says Dr Naomi Doak, Greater Mekong programme coordinator at Traffi

The highest levels of the government seem implicit in the trade, with its effectiveness in curing cancer supposedly originating due to an unnamed government official recovering from the condition.

South Africa currently has a stockpile of more than 18 tonnes of horns, in government and private hands, and is going to lobby at the 2016 CITES meeting for a one-off lifting of the trade ban. “People are gambling on the rhino’s extinction and are speculatively stockpiling,” says t’ Sas-Rolfes, who claims that poaching only becomes economically attractive at a certain horn price level.

John Hume, who owns about 900 rhinos, thinks that the answer is farming the rhino. “Whether rhino horn can be scientifically proven to work as medicine is most likely irrelevant to those who use it,” he says. “Ironically, there is no need to kill one single rhino for the consumers of horn as rhino horn is a renewable resource that can be easily harvested.” An African white rhino can yield as much as one kilogram per year, while a killed animal provides only three kilograms. In contrast, a living animal can offer as much as 60kg in its lifetime.

Such a move is not without precedent. The South American vicuña was hunted to near extinction for its wool, but with sustainable harvesting and giving the local community an economic incentive, numbers increased from about 10,000 to 421,500.

In South Africa, about three-quarters of protected areas are privately owned, whereas in Kenya the big game population dropped by more than 50% after outlawing such areas in the 1970s. This may sound anathema to conservationists, but “you don’t need a lot of rhinos to keep tourists happy. In South Africa, most of the expansion of the wildlife population has been driven by hunting,” says t’ Sas-Rolfes.Rhinos are teetering on the brink. Current measures to cut demand in Vietnam are not working and, unless a workable solution is found, an animal that has been around for up to 15 million years will go extinct on our watch.