When Nicole arrived at her hostel in the Vietnamese capital Hanoi on a warm February afternoon, exhausted but excited, she presented her Chinese passport at the check-in counter and was promptly told that her booking had been cancelled and she could not stay there.

“I asked the reason for it, and they said, ‘All the rooms are booked now.’ And I checked immediately [on my phone] and they had four rooms available,” she explained.

When Nicole – whose name has been changed upon request – booked a ten-day vacation in Vietnam from January 26 to February 6, she expected a lively adventure. But like many Chinese people living, working, studying and travelling in Southeast Asia (as well as across the globe) in recent weeks, she has experienced rejection and hostility as sinophobia has grown following the coronavirus outbreak.

Reported incidences have impacted a range of people – from small children in England, to university students in Canada, to the elderly in Australia– in countries with small Chinese communities and huge, longstanding diasporas. Given the region’s proximity to China, somewhat inevitably strong responses have also been seen in Southeast Asia.

A petition in Singapore calling for the government to ban mainland Chinese nationals from entering the country has garnered 25,000 signatures, while in Malaysia, a similar petition received almost half a million signatures in just a week. According to the Associated Press, Indonesians also held a march near a hotel in early February calling on its Chinese guests to leave, and in the Philippines, Abner Afuang, a former town mayor and police officer, stood in front of the National Press Club in Manila and burned a Chinese flag to protest China’s impact on the country and other Southeast Asian countries, including coronavirus.

In Vietnam, with its shared border with China, the government has implemented some of the most robust measures in response to the virus. These have included a ban on all flights to and from China, calls for the quarantining of workers who have recently returned from China, schools and universities being shut down, and most recently the quarantining of the 10,000 residents of Son Loi commune just outside of Hanoi.

Whether the measures are proportionate or not, at the local level, Chinese visitors and residents are struggling in this securitised environment fuelled by fear and scrutiny.

One user on a Hanoi expat Facebook group complained of being told by a prospective landlord that Chinese residents were not permitted in the building, providing screenshots of the incident. His is one of many such cases in the country that have occurred as fear of the virus has grown.

Shan, whose last name has been withheld to protect her identity, has been travelling since 2018. She relocated to Hanoi for a while and then eventually moved to Da Nang in central Vietnam for work a few months ago.

The 25-year-old from Shenzhen told Southeast Asia Globe her countless positive experiences in Vietnam have been overridden recently by unsettling incidences. Drivers with the popular ride-sharing app Grab have been scared of her, and on buses, she hears whispers that drift in her direction. These days, she says, she’s “scared to say I’m from China, scared to talk to other Chinese people in public”, even though she feels like she has skirted the brunt of it.

“Some people are scared to talk,” she added, pointing out the backlash many Chinese people are receiving online for speaking out about their experiences. “But I don’t want to be that kind of person.”

While in Vietnam the government’s response has been robust and very public, in contrast, Cambodia, a country with increasingly close political and economic ties to Beijing, the outbreak has been notably played down.

In late 2018, a piece in The Diplomat linked an influx of Chinese tourists and expats to “increasing anti-Chinese sentiment among Cambodians – who are becoming increasingly angered by the perceived bad behaviour of these newcomers and fear their country is being sold off” – but at the state level Hun Sen is keen to foster a different image of the nations’ ties.

The Kingdom has only had one confirmed case of coronavirus, a man who has since fully recovered, and Hun Sen has been vocal about his unwillingness to turn his back on China, instead encouraging investment and partnership between the countries.

He was also the first head of state to visit China during the crisis, labelled a “special visit”, with Chinese President Xi Jinping calling this a demonstration of “unbreakable friendship and mutual trust” between the nations. The prime minister even offered to go to the epicentre of the virus in Wuhan.

In another show of solidarity, on Thursday morning, the MS Westerdam cruise ship – which was rejected by five ports, including in Thailand and the Philippines, despite having no diagnosed cases of coronavirus on board – docked in Sihanoukville, with Cambodian ministers of health, transport and tourism present to greet it. The ship was filled with 1,455 passengers who will now be transferred on chartered flights to Phnom Penh and allowed to travel home from there.

“We must work together to save those stranded in cruise ships regardless of their races,” Hun Sen said yesterday in an interview with state-aligned outlet Fresh News.

The WHO’s Ghebreyesus praised Cambodia for this approach, saying, “This is an example of the international solidarity we have consistently been calling for.”

But an alternative explanation is Cambodia’s increasing economic reliance on Beijing, which could explain the government’s desire to downplay fears surrounding coronavirus, with Hun Sen arguing that cancelling flights to and from China would amount to economic suicide for the Kingdom.

Initially labelled online as the “Wuhan virus” during its early days, on February 11 the World Health Organization (WHO) officially named the virus COVID-19. The WHO intentionally avoids associating illnesses with places, people or specific animals in its naming to avoid stigmatising a geographic area or a population group.

One prominent example of the ill-effects of doing this is AIDS. Before it received its official name, it was unofficially dubbed GRID, or Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, a name which bolstered homophobic fears while failing to highlight the vulnerability of intravenous drug users and people seeking blood transfusions to contracting the disease.

It’s a common phenomenon … With outbreaks and epidemics along human history, we’ve always tried to vilify certain subsets of the population

Rob Grenfell, director of health and biosecurity for CSIRO

“Having a name matters to prevent the use of other names that can be inaccurate or stigmatising,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General, said in a statement on COVID-19 this week.

“It’s a common phenomenon,” Rob Grenfell, director of health and biosecurity for Australia’s science and research agency CSIRO, told AFP. “With outbreaks and epidemics along human history, we’ve always tried to vilify certain subsets of the population.”

“Sure [coronavirus] emerged in China, but that’s no reason to actually vilify Chinese people.”

As academic Aruuke Uran Kyzy pointed out, there may be a wider political and economic underpinning to this vilification of the Chinese, one that signifies this sinophobia may not fade with the end of coronavirus in Southeast Asia.

Kyzy, a researcher with TRT World and a journalist who regularly contributes to news and analysis to The Diplomat, has been studying the Central Asia region for years. In October, months before the first coronavirus cases were reported, she wrote a piece that aimed to explain why anti-Chinese sentiment was on the rise.

“For now, the ‘Chinese question’ provides a kind of catharsis – a focal point for frustration and tension built up over the, at times rapidly changing and tumultuous, last three decades in Central Asia,” Kyzy wrote. “But it is also within this context of intensified animosity toward China that Beijing now struggles to find the means to both further and then protect its own national, strategic, and economic interests in Central Asia.”

Moreover, as China moves to expand its Belt and Road ambitions and cleave Chinese industry into the entire Southeast Asian region, Kyzy says, the country has taken on the role of “scapegoat for local grievances”.

In Vietnam, a country which shares a 1,281km border with China, there is a torrid history with its neighbour to the north. In the late 1970s, Vietnam repelled China in a border war that killed 50,000 people, and nationalistic Vietnamese hold memories of bouts of colonisation and conflict with the Chinese over the centuries. To this day, they continue to clash over maritime and territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

So while coronavirus is not the origin of much animosity towards the Chinese in Southeast Asia, it may just be giving new life to old grievances.

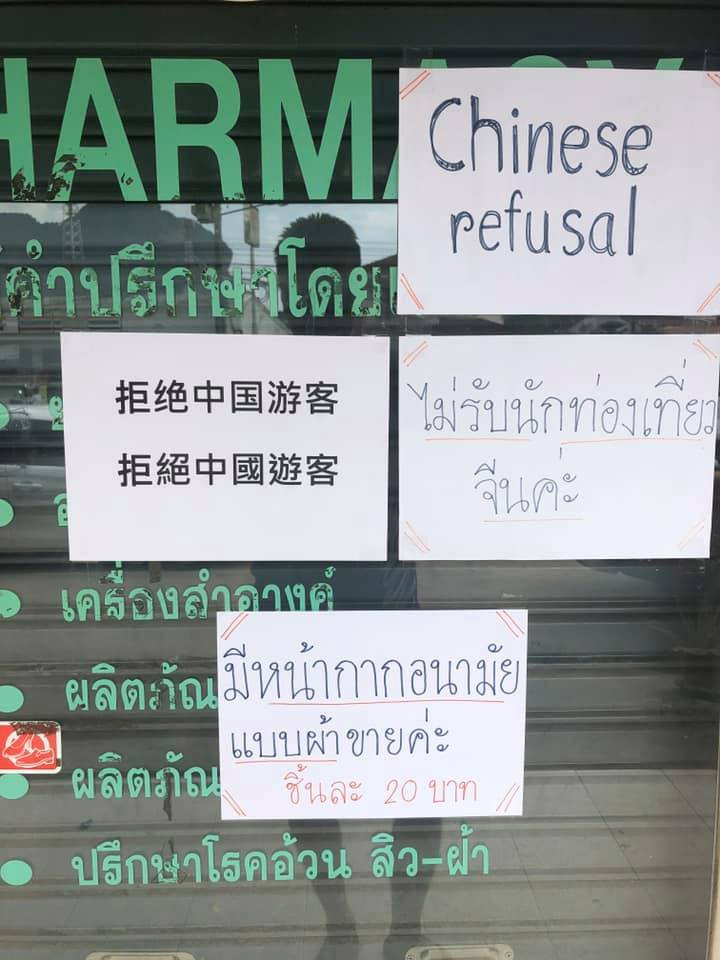

For the rest of her vacation in Vietnam, Nicole saw people put on masks when she started speaking to them and had to skip restaurants because they had signs reading “No Chinese” or “No Mandarin speakers” out front. The 28-year-old from Guangxi province was tempted to challenge this last sign, as she speaks three languages fluently.

On February 5, a local travel agency informed her that her tour bus in Da Nang was no longer running because of the virus, and her booking was cancelled. She saw it picking up passengers at one of its marked stops in the city later that day.

Some of the incidences were almost funny in their ridiculousness, she said. On February 2, when she was on a plane from Hanoi to Da Nang, the boys seated beside her heard her speaking Mandarin with a flight attendant and began whispering about how she must be infected.

Then, an older man sitting directly in front of her – who was already wearing a mask – pulled another mask out of his bag and layered it over the first. He was likely making “double sure”, she laughed darkly, explaining the way she was seen in the country as like a “moving virus”.

Finally, I realised we do the same thing to the Wuhanese

Nicole, a Chinese woman recently in Vietnam

Nicole also traces the behaviour surrounding coronavirus back to a basic human emotion, one she actually finds quite reasonable: fear. At first, bearing the brunt of these incidences and finding them happening to friends all around her, she felt angry and frustrated with what was happening.

It was only upon her return from Vietnam that she began to notice that people in China were acting similarly towards people from Wuhan, the city where coronavirus originated.

“Finally, I realised we do the same thing to the Wuhanese,” she said.

Fuelling the fear is social media. One now-infamous video that initially went viral on Twitter, of Chinese celebrity Wang Mengyun eating bat soup, is one example of fake news that threw fuel on the fire of vitriol. The video was actually filmed in Palau, Micronesia, for a travel video in 2016.

Nicole mentioned that she has seen countless YouTube videos spreading misinformation or content tinged with anti-Chinese sentiment. A recent Buzzfeed News investigation found that among 500 of the most-watched YouTube videos featuring the keyword “coronavirus”, “dozens included unconfirmed or made-up facts”.

Social media companies are striking back, using new strategies in an attempt to curb misinformation spread on their platforms. As of this week, when Instagram users search for the hashtag #coronavirus, a notice appears encouraging them to find credible information on the website for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facebook, Instagram’s parent company, has said that it will also be conducting “proactive sweeps” on hashtags spreading rumours and falsities. Twitter is doing something similar.

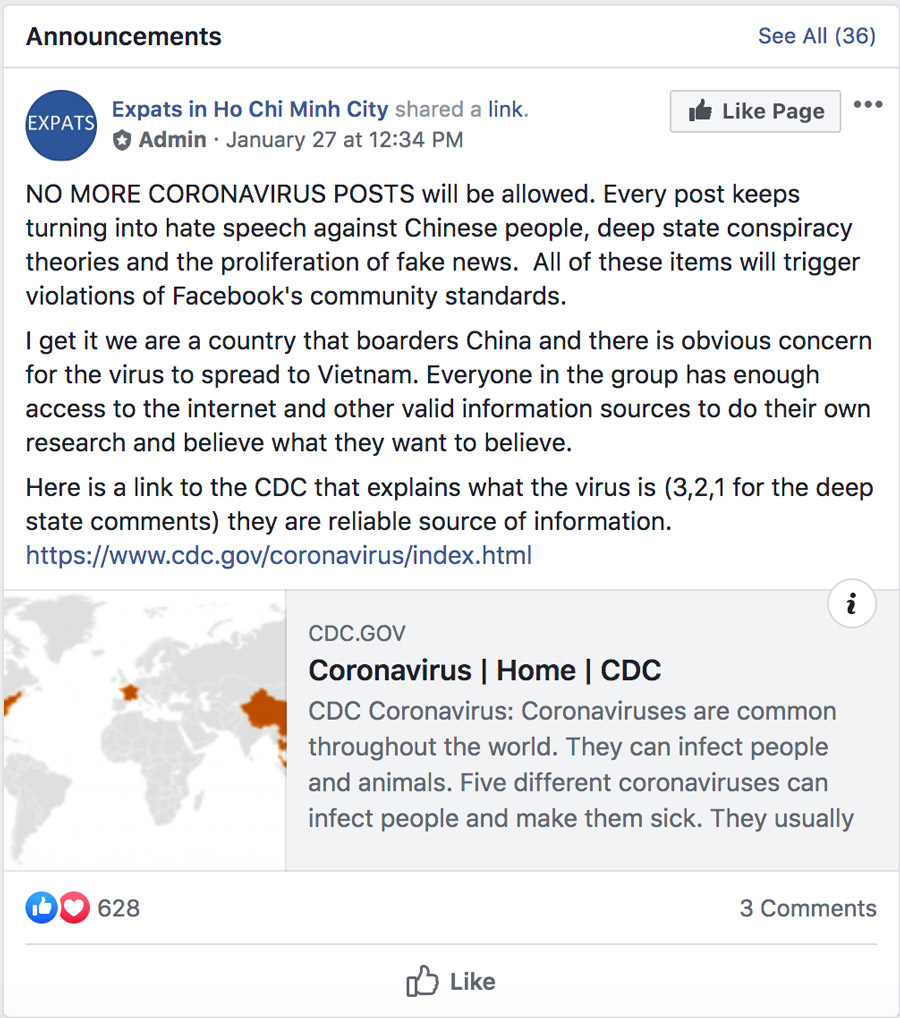

Though the two are often linked, most of the action on the part of social media platforms is specifically to combat misinformation, not hate or discrimination against specific groups. To fill these gaps, some individuals are taking action into their own hands – several moderators of Facebook groups for expats living in various Southeast Asian cities, for example, have banned posts relating to coronavirus from their platforms.

“Every post keeps turning into hate speech against Chinese people, deep state conspiracy theories and the proliferation of fake news,” the moderators of group Expats in Ho Chi Minh City wrote in an announcement pinned to the top of the page. All posts mentioning coronavirus were deleted in the group.

Nicole finds the vigorous approach to combating misinformation helpful, but at the end of the day, hopes that empathy plays a large role in how people think about coronavirus.

“After this virus, I hope that people will not look at Chinese people just as a virus. It will take time for Chinese people to recover. And I hope people will treat us nicely,” she said.