Through the middle of Phnom Penh runs a fetid stream, a canal, in the loosest sense of the term, known as Boeng Trabek that shuttles rainwater and human waste to the flooded fields and wetlands south of the city.

In some parts along the concrete banks of the canal, there are high-rise apartments and other modern developments, places that are comfortable enough, if a bit putrid smelling when the water is low. But in other parts, especially the neighbourhoods downstream just north of the Boeng Trabek Water Station, the situation is more dire.

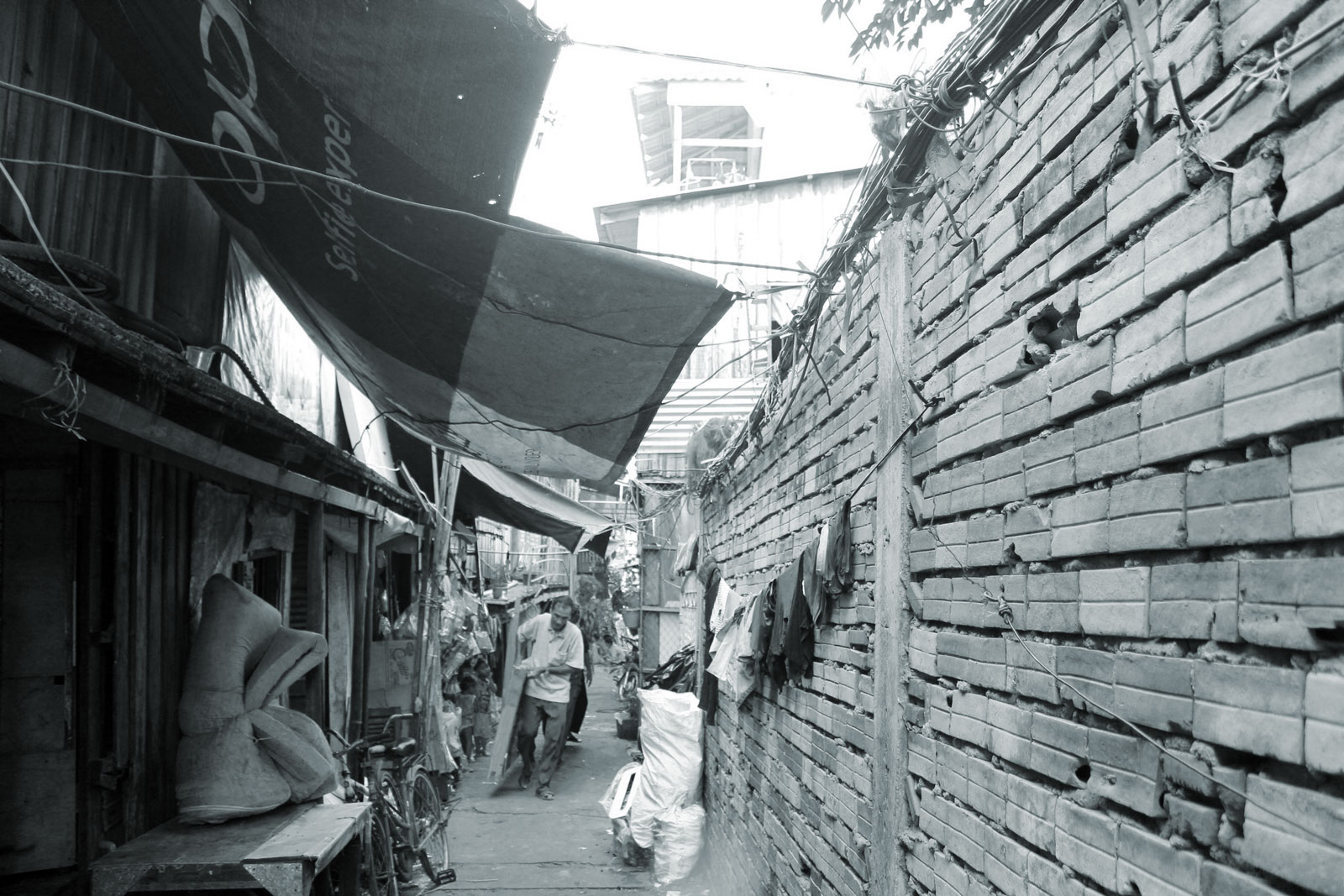

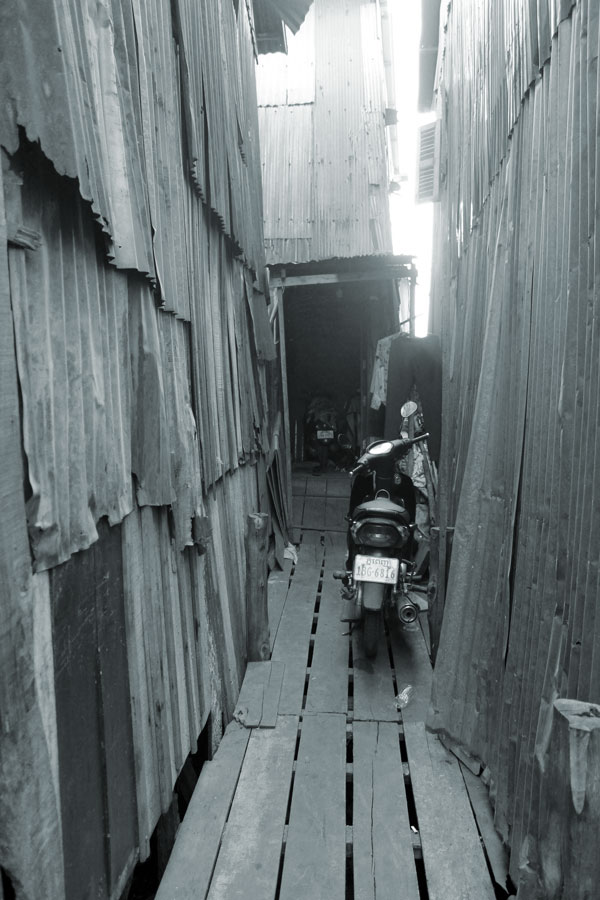

As the pavement gives way to muddy, almost-natural banks, the canal widens into a flat river of decay. Within this pooling, the water bubbles, churned with the gases of decomposing material, and over this toxic swamp juts a collection of stilted, clapboard homes.

In this neighbourhood of the Cambodian capital, one of several communities clustered on unpaved banks rougher than those in wealthier areas upstream, the houses sit on wooden platforms just above the foul mud and water.

There are some 400 people here in Boeng Trabek alone, in shelters ranging from plastered homes to gap-boarded shacks. Children run barefoot on the narrow boardwalks and, on firmer land, amid the dirt and scraps of material in a hard-packed courtyard.

Her house is next to the drainage site and river bank … She’s concerned because it’s affecting her house and could make it collapse into the river

Chamnan Chhun, a coordinator with Planete Enfants & Développement

Urban rights NGO Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT) has been working in the neighbourhood for years says organisation leader Soeung Saran, and has recorded countless issues from fears of eviction, to myriad health problems related to poor sanitation.

“They are the poor of the poor,” Saran said in the STT offices, not far from the canal.

His organisation completed a survey of the city in 2018 that identified 277 urban poor communities. Though the communities around Boeng Trabek are particularly blighted, the hopes and challenges of their residents tend to closely align with those experienced elsewhere across the capital’s metropolitan area.

East of Boeng Trabek, Daeum Chan also offers a glimpse into the state of Phnom Penh’s poorest neighbourhoods, many of which are clinging to the banks of the city’s waterways.

Across the much wider waters of the Tonle Bassac, Daeum Chan is just one of a line of communities hugging the waters below Monivong Bridge. On a recent afternoon, a group of mainly female residents adjourned their monthly meeting to discuss the most pressing issues of the day.

This month, said Chamnan Chhun, a coordinator with Planete Enfants & Développement (PED), an NGO that works in part as a liaison between the government and urban poor communities, the meeting agenda had focused on drainage.

The age-old question here is how the waste- and rainwater of the neighbourhoods can be carried into the river with minimal erosion and stench. Though local authorities have been cooperative, much of the infrastructure in these communities is built with assistance from NGOs.

The new facilities have improved life for many. Though some are still in perilous shape.

“Her house is next to the drainage site and river bank” Chhun said, gesturing to a woman in the crowded room. “She’s concerned because it’s affecting her house and could make it collapse into the river.”

Residents here are subjected not only to the rise and fall of floodwaters – dirty tides that damage homes and usher in periods of heightened illness – but also to the vulnerabilities inherent to the landless poor in a city where encroaching construction is threatening their low-rent way of life.

Sokhom, 68, is a long-term resident and community representative of a village along the Boeng Trabek canal. Her reasons to stay here are simple.

“Over here, it’s dirty, but it’s close to the public schools and healthcare,” she said through a translator. “The environment is not good but we’re happy to live here because we can access anything and make a career.”

Sokhom lived in Kandal Province when she was young. She says her father died during the Khmer Rouge years, after which she migrated to Phnom Penh and settled in her current home, a modest structure on the edge of the boardwalks hanging over the canal.

Sitting on the steps of her house, a wood and corrugated metal building decorated with small effects and potted plants, Sohom is well aware that her current neighbourhood has its problems. Still, in her opinion, the biggest issue the community faces is the insecurity caused by the lack of legal land titles.

According to PED, the true ownership of much of the canal and river-side property is fuzzy; some is privately held by unknown holders, and much is public land held as a buffer along the water. As Phnom Penh expanded over recent decades and filled in with waves of new residents drawn from around the country, settlers put down roots wherever they could find room, no matter if that meant edging up to – or over – bodies of water.

Residents here along Boeng Trabek, and in the other “unsettled settlements” of tenuous or unrecognised legal claims to property throughout the city, have watched as past evictions cleared out whole neighbourhoods.

In 2015, not far from Sokhom’s house, the homes of an estimated 400 people were marked with red paint and slated for removal as the city and local district resolved to protect the natural reservoir of Boeng Trabek, which had been gradually filled in for new construction.

There’s a soft title, recognised by local authorities, and a hard title, which is delivered by the Ministry of Land Management … The soft title is good, as it can protect against eviction

Pierre Larnicol, a project manager at PED

Looking farther back, the city’s landless poor took a hard lesson from the infamous evictions of residents at Boeng Kak, a former lake in the north west of the city that was filled in as part of a redevelopment plan announced in 2007.

Thousands of people who lived along its shores and depended on its waters to make a living through fishing and cultivation were controversially pushed aside, many relocated by the government with the help of one-off payments or the promise of land elsewhere, sometimes far from the city’s core. Tense protests against the plan lasted more than a decade, but yielded few results for the former residents.

Removed from the socioeconomic prospects of Phnom Penh, the uprooted communities were left with little to grow in the dusty soils of neighbouring provinces. For the residents of the capital’s canal-side, there was a lesson in the fate of those who eventually relocated from Boeng Kak: Neighbourhoods like theirs might not be pretty, but their central locations make it worth it to dig in and access better jobs and public services.

In a city where gentrification and mass redevelopment has limited housing supply for the very poor, communities like Boeng Trabek are getting harder to come by in Phnom Penh.

Even if the residents like Sokhom have been there for decades, the members of these communities typically have few real guarantees to the places where they live.

“The key challenge is the land security,” STT’s Saran said.

Without a title, he says, they have no right to build new homes or even make substantial renovations. That tenuous legal connection to the property can also leave community members in a vulnerable position if and when their neighbourhood falls under the attention of a developer in construction-happy Phnom Penh.

Ownership is recognised, at the very least, among the people who live in these communities, with property changing hands as residents buy, sell and rent amongst themselves. However, according to Pierre Larnicol, a project manager at PED, informal deals often aren’t recognised outside of the village, even if they involve documents between parties.

“There’s a soft title, recognised by local authorities, and a hard title, which is delivered by the Ministry of Land Management,” Larnicol said. “The soft title is good, as it can protect against eviction.”

Hard titles are as close as you’d get to a gold standard in Cambodia, but soft titles can be a powerful document to have in hand should residents face eviction. In most instances though, residents in Phnom Penh’s poorest communities have neither.

Eviction still isn’t far from the thoughts of many who live in these urban poor settlements, though in recent years some of the most acute fears have dissipated.

Kong Sovana, 37, has lived near the Boeng Trabek canal for more than a decade after moving to the neighbourhood with her growing family. She runs a small business now, sewing in a front room that also serves as salon – as she works, another woman is getting a manicure just a few feet away.

Sovana is content. Despite the harsh conditions, she’s managed to make a living and send her four children to nearby schools. If and when development comes, she wants to stay put, and she’s looking for options to secure her place here even if bulldozers show up.

“No, although we don’t have land titles here, we’re happy,” Sovana said. Her family intended to request a title from the government and, down the road, believed they “still need to appeal to the government to develop” the community.

Part of the work of the urban rights NGOs is to help those processes along. Chhun, the PED coordinator, said the municipal authorities of Phnom Penh were uneasy with the idea of more confrontations and evictions like the ones at Boeng Kak. According to Chhun and Larnicol, the city government has expressed an increasing willingness to allow residents of these communities to renovate their homes and upgrade their surroundings.

So far, that has meant extending some city services, such as drainage and sanitation systems, into communities that had previously made do without.

“The Phnom Penh City Hall told us a few months ago that now they want to keep most of the people living in the urban poor communities on-site and support them in upgrading their communities, provide them with land titles,” Larnicol said, pointing to the 2018 Stung Meanchey canal renovation project as a possible case study. “For us, it’s a good solution.”

City authorities did not respond to requests for comment, but if they truly have changed their tune with the landless, urban poor after decades of a more combative approach, it would be welcome news to residents who have no desire to move.

Chhun and Larnicol cite a recent PED survey of some 335 families in urban poor communities that found overwhelmingly that the residents preferred solutions that allowed them to remain where they were currently living.

Rather than just a temporary staging area to better neighbourhoods, Larnicol said, about 89% of those surveyed had plans to stay long-term, with nearly the same number reporting a feeling of strong community ties with those around them.

“Many families have lived there for a long time, Larnicol said, “They feel this is their home.”

Sok Chan Sakhorn, 70, knows the feeling well. She moved in 1990 to her current home in the village next door to Daeum Chan and, though she doesn’t have a title to her land, she bought it from its previous owner in a deal recognised by local authorities. Before, only a few houses stood near hers on the muddy, improvised road that ran atop the banks of the Tonle Bassac. In the years since, more settlers have come from the provinces to build homes of their own.

For about a decade she’s been the community’s representative, organising collaboration with NGOs and local government leaders to develop the village.

“The situation here is much better than before,” she said, listing the contributions from outside organisations. Though Sakhorn was happy with the progress, she said there was much to be done in her neighbourhood.

She said, however, that would be left to the new generation, whose leadership she hoped would reshape this place yet again.

“I am quite old to be leading the community,” Sakhorn said. “If I share the visions, the ambitions to develop the community, I am concerned I won’t fulfill their dreams.”