Since April last year, school director Ros Pisey has seen her classrooms at Trapaing Trom Primary School in Siem Reap province converted into makeshift quarantine wards to house Covid-19 patients.

Before it was converted to a quarantine centre, Trapaing Trom school had instructed 434 primary students in Grades 1-4. Though the school’s students are still technically in class thanks to distance learning, Pisey said the transition away from in-person instruction is leaving many of her students behind.

“During the pandemic, the students have not been able to learn properly or adequately,” Pisey told the Globe. “While the school is closed and used for quarantining, we fear the spread of Covid-19 and we see that the children are spending more time at home doing housework or in the rice fields leaving them prone to risk.”

Prior to the pandemic, Cambodia was already off-track to meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on quality education. Even before the pandemic, in 2019 the World Bank estimated approximately 190,043 children of primary school age, or around 9% of the total, were out of school in Cambodia.

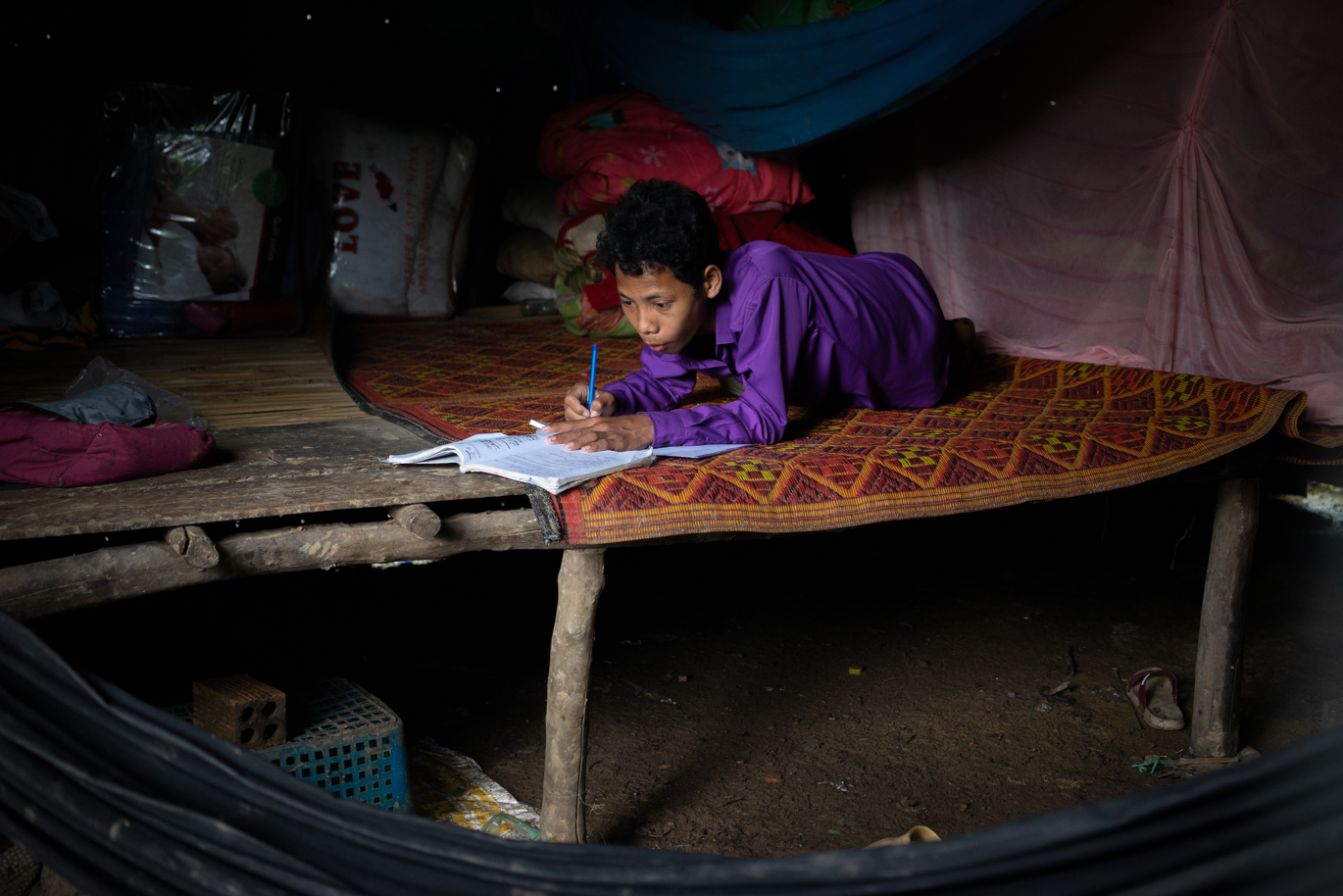

The onset of Covid-19 has only added to this. Since March 2020, Cambodian schools have been closed for more than 200 days, interrupting learning for approximately 3.2 million students and creating an unprecedented educational emergency. While school administrators have turned to distance learning as a stopgap, a Joint Needs Assessment from the Cambodian government published earlier this year suggests 30% of students have not accessed education at all during the suspension of in-person learning. If closures continue, teachers are concerned their more vulnerable students may drop out of school entirely.

In a school down the road from Pisey, teacher Chea Seiha shares her concerns over the quality of education during closures. When Seiha resumed classes for students with disabilities in her school in Siem Reap after six months of closures in 2020, she found not only had her students’ academic and social abilities decreased, but also found about 30% of her students, all female, had simply not returned. Her students are not an unusual case. Research conducted by Save The Children Cambodia found students with a disability had a 7.7% higher risk of drop-out than students without a disability during school closures.

Even for Seiha’s students who remain engaged with their education, the five additional months of closures this year have worsened learning outcomes.

“I’ve been unable to teach them anything new,” she told the Globe. “I feel there have been no achievements for the children at all.”

While administrators have implemented distance learning programmes – such as those on TV, online and radio broadcasts – the Cambodian government’s Joint Education Needs Assessment revealed unequal learning opportunities are leading to substantive learning losses across all levels.

The research found just 70% of Cambodian students have been able to continue learning during school closures, with only 30% accessing online learning materials and 32% relying on paper-based materials. Of those learning, only 12% are spending more than three hours per week engaged in distance learning, compared to several hours per day in class pre-pandemic.

The needs assessment highlighted that during a normal school holiday, about 8–10 weeks, there is typically a 10–15% drop in literacy skills among students, especially in early grades where children are still learning basic reading skills. With extended school closures of 25 weeks, learning loss research estimates 40% as a worst-case scenario. Currently, Cambodia is approaching its 20th consecutive week of school closures.

The alternative is inconceivable; Covid-19 will have successfully undone generations of hard-earned development progress with far-reaching implications into the future

Mary Joy Pigozzi, executive director of Educate A Child (EAC), a global programme of the Education Above All Foundation, says the Kingdom’s prolonged school closures are impacting the most marginalised populations.

“The most vulnerable children – those who are geographically isolated, not to mention those who were out of school beforehand – have firmly borne the brunt of the Covid fallout,” Pigozzi said.

In partnership with Educate A Child, international non-governmental organisation Aide et Action signed a November 2020 memorandum of understanding with the Cambodian Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport to increase access to equitable education. This would mostly come through the second phase of the Cambodian Consortium For Out of School Children, a four-year initiative made up of over 20 local nonprofits to support more than 100,000 marginalised children with educational opportunities.

“It is absolutely critical that education stakeholders continue to work together, to find new and creative ways to close the funding gap, and invest in access and quality education for every child,” Pigozzi said. “The alternative is inconceivable; Covid-19 will have successfully undone generations of hard-earned development progress with far-reaching implications into the future.”

In a joint statement released in July urging governments to reopen schools globally, UNICEF and UNESCO stated “schools should be the last to close and the first to reopen” as evidence suggests primary and secondary schools are not among the main drivers of Covid-19 transmission.

Despite UN agencies urging governments and other decision makers not to mandate Covid-19 vaccination prior to school entry, Cambodian classrooms appear to be closed until the completion of the ongoing inoculation of approximately 2 million children aged 12-17. However, that rollout began on just August 1 and, with each week that passes, learning losses are only increasing.

But while the average Cambodian child struggles through the pandemic, the situation is worse for those on the margins.

For public primary school teacher Cha Paulang, indigenous students in her Grade 1 class in Mondulkiri province have been largely locked out of education during school closures due to their limited knowledge of Khmer language and a lack of educational resources in their mother tongue. House visits, printed worksheets and radio broadcasts in minority languages are the main methods of distance learning for her students.

But according to Paulang, whether a child is learning during school closures largely comes down to the parents’ abilities to support them at home.

“During my house calls, I can see that not all kids are learning during school closures because some have parents to help them at home and some don’t,” explained Paulang, who has to visit 37 students per week during school closures.

According to the government’s needs assessment research, only 23% of caregivers reported being able to support distance learning all of the time. It also found the most commonly reported barriers to accessing distance learning programmes across all school levels were financial constraints to pay for internet or devices to access online learning (51%), internet connectivity problems (43%), lack of content knowledge among caregivers (22%), and a lack of caregivers’ time to support learning at home (20%).

In addition to learning less, students are also taking on a larger share of domestic responsibilities during school closures. Over half of the respondents of the assessment (61%) reported that children were required to contribute more to household chores since the pandemic.

I can see that not all kids are learning during school closures because some have parents to help them at home and some don’t

In Phum Thmey village, Kampong Thom province, primary school director Sreng Bonat estimates as many as 70% of her school’s students are spending more time doing housework than schoolwork. She’s also noticed female secondary school students in her village have started working as housekeepers and boys as young as 13 years old are leaving the village in search of work, typically in the construction sector.

In Poipet city, teacher Chom Srey Touch shares similar concerns over whether those who have found work will ever return to class.

“I think the closures are greatly impacting students – the lack of practice and instruction are causing them to forget what they have learnt,” she explained. “If the closures continue I’m afraid that they will stay in the jobs they’ve found and never return back to school”.

Approximately one-fifth of students in Srey Touch’s school, an education centre run by local nonprofit Damnok Toek, are missing out on distance learning since March 2020 due to increased levels of poverty. Of these, half left the city with their parents in search of work in the countryside as the city’s economic prospects dried up and their families could no longer afford to pay their rent. The other half found work during school closures and could no longer find the time to study.

With children on the move with their parents, teachers are also struggling to contact them and check up on their education. For students without mobile devices or access to the internet, weekly printed worksheets are the only line of communication they have with teachers.

But even with new digital tools and lesson plans for distance learning, teachers and school administrators told the Globe they fear nothing can compete with the value of in-person teaching. One director in Kampong Thom province said her teachers are trying to get as close as possible to students while still maintaining a safe social distance, teaching the core subjects of Khmer and mathematics outside of the classroom under the trees and giving them homework.

For Ros Pisey, teaching outside in her schoolyard remains out of question as long as the school continues to operate as a Covid-19 quarantine centre. Only teachers are allowed through the school gates to print out lesson sheets to be delivered individually to students.

But without classrooms and students, the school doesn’t quite feel like a school anymore, explains Pisey.

“The school is so silent now,” she said, missing the chit-chat and laughter of the students who had previously filled her classrooms. “We don’t know when it’s going to return.”

This article has been written by Aide et Action as a part of a partnership with Southeast Asia Globe to highlight the need for equal access to education in the region. Find out more here.