Jumping down from the tree near her home, Srey Ka assumes her spot in the shade underneath as she adjusts the dials on her radio. Her pet piglet remains asleep at her feet, twitching his nose as he dreams, his belly full of leftover rice. Around her, cows meander by, their ringing bells competing with the sound of static from her radio.

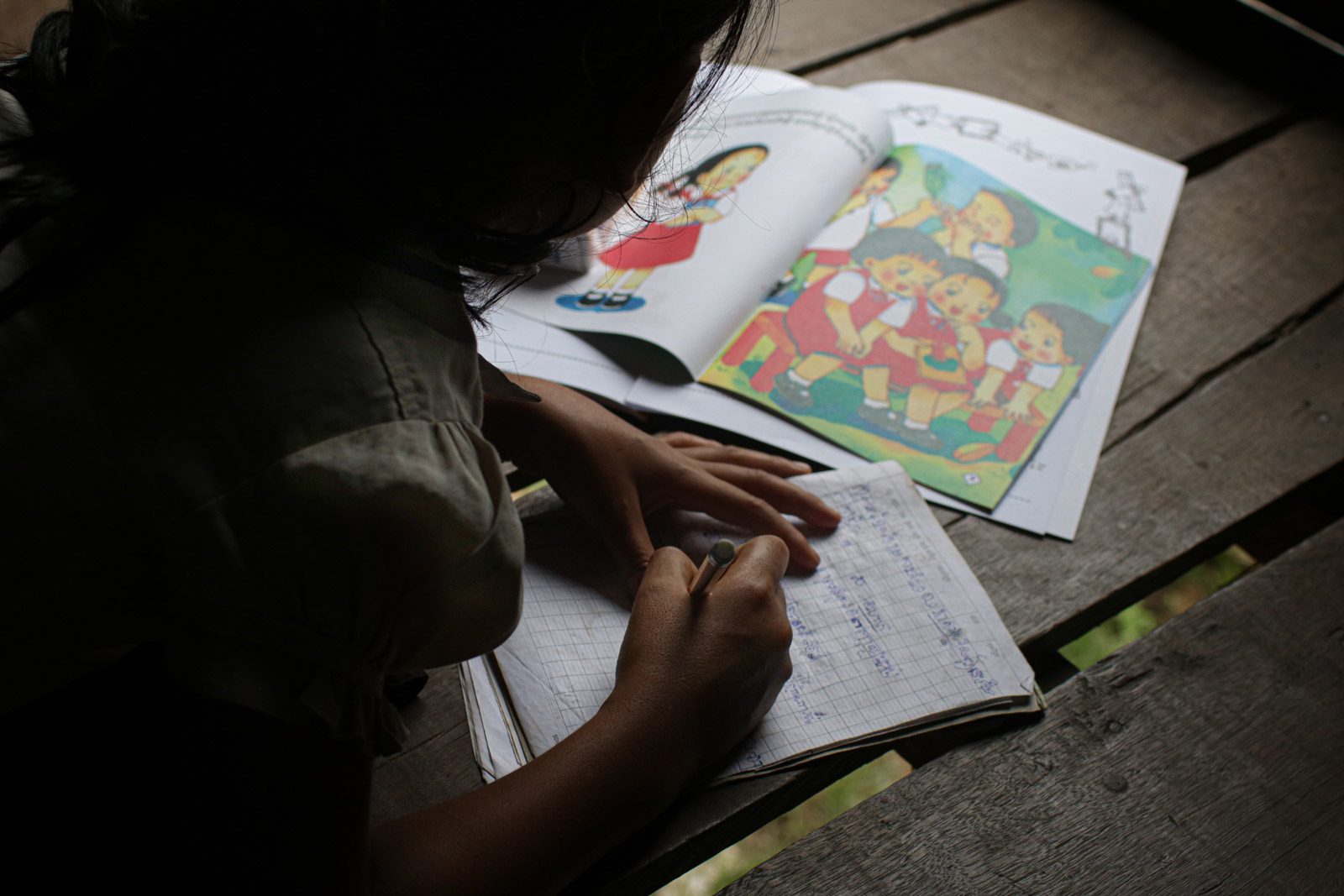

While her school is still closed due to Covid-19 regulations, she still wears her Grade 3 uniform as she attempts to locate a signal. She’s listening out for distance learning programmes – six hours of educational radio broadcasts per week for children in Grades 1-3, some of which are in her ethnic minority language.

It was August and Srey Ka had just received a radio from international nonprofit Aide et Action, two weeks before her school reopened as pandemic measures eased in Cambodia in early September.

From the Phnong ethnic minority group, Srey Ka struggled to find learning resources in her language during school closures. Eager to cram as much as she can before returning to school, Srey Ka tied the antenna of her radio to the highest point of a tree to get the best reception. Even a clear radio signal is hard to come by in the small fishing village of Pun Thachea, located along a remote stretch of the Mekong river in Cambodia’s northeast Kratié province.

When she’s not studying, Srey Ka also takes care of the animals and helps her father in the family’s nearby rice fields. Students dropping out of school to support parents with farmwork is a high concern among teachers in many of Cambodia’s rural provinces.

Even without the threat Covid-19 poses to education for marginalised students like Srey Ka, completing a secondary education remains out of reach. With secondary schools located too far from villages, many children will study only as far as Grade 6. According to a 2018 study by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport, the gross national enrollment rate at lower secondary school is 59.2% and the competition rate is just 46.2%.

This cycle of poverty and illiteracy is one that Srey Ka’s mother, Andout Theary, knows all too well. “When I was a child, we studied under a mango tree because we had no school building,” she remembered. Theary herself doesn’t own a smartphone to this day, and said she had never used the internet.

Schools across Cambodia reopened in early September, but as many class sizes needed to be reduced to adhere to new protocols (a maximum of 20 students per class), children will typically attend just 2-3 days per week, with the expectation for them to learn at home for the remaining days using homework and distance learning materials like computers.

For students like Srey Ka, the only distance learning material she has is her radio.

When I was a child, we studied under a mango tree because we had no school building

Currently, the radio broadcasts are being aired only in the evenings. Samphors Vorn, Country Director of Aide et Action in Cambodia, feared this may prove challenging for children who do not have electricity in their homes, meaning they would listen in the dark and would be unable to write and fully engage. Now, with financial support from Aide et Action, the broadcasts’ airtime is set to be doubled and will be played in the mornings too.

Building more inclusive learning strategies like the radio programme has been a collaborative effort between the Ministry of Education and international nonprofits such as Aide et Action, CARE International and UNICEF.

Radio is important because it supports our language. Our young students need to be able to learn in their own language. It is essential

Pun Bunlea, a primary school principal in Mondulkiri province hopes that the radio programme will be a stepping stone to creating further programmes in minority languages for TV and social media. Two of the teachers at Bunlea’s school have been recording the broadcasts weekly at the local radio station since the early days of the pandemic in April.

“Radio is important because it supports our language,” said Bunlea. “Our young students need to be able to learn in their own language. It is essential.”

This article has been written by Aide et Action as a part of a partnership with Southeast Asia Globe to highlight the economic fallout of Covid-19 for poor Cambodian communities. You can read more stories written by Aide et Action on social issues impacting the region here.

![[Photos] Armed with a radio, Cambodian girl climbs tree to access education](https://southeastasiaglobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Cambodia-radios_03.jpg)