The exhibition hall stretched as far as the eye could see: hundreds of booths representing dozens of sectors, both local and regional, put their best tech-foot forward at the first annual Digital Cambodia conference. Startups and telecoms set up their booths beside those of banks and events companies, while gamers played on premium operating systems at the east end of the hall and dozens of speakers led a series of panels at the west end.

Located on Phnom Penh’s Diamond Island, the Digital Cambodia conference – the first of its kind to be held in the Kingdom – attracted 120 exhibitors and nearly 100 speakers, all of whom gathered to discuss the oncoming digital revolution and its impact on their respective industries. Over the course of the three-day event, which took place March 15 through March 17, thousands of attendees poured through the exhibition’s halls to attend the panels, talk with industry insiders, and fully immerse themselves in all things digital.

The conference attracted not only dozens of local figures, but also ministers and startups from six other Asean countries including Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia and Singapore – each of which have taken their own approaches to embracing a digital future, and whose input is invaluable to a country that has yet to adopt a cohesive digital policy.

“Digital Cambodia is about showcasing the digital transformation here in Cambodia, where many outsiders might think there is not much happening,” explained Dr. Seng Sopheap, the president of the National Institute of Posts, Telecoms and ICT (NIPTICT), which organised the event. “We may not yet be Singapore, but there have been a lot of digital initiatives, competitions and programmes set forth in the past two years here in the Kingdom.”

Modest Progress

Over the past decade, Cambodia’s entrepreneurs have stepped up their game to create a small but growing tech startup market in the Kingdom. Multiple competitions are hosted each year by incubators like Impact Hub in union with various private sponsors, each aimed at fostering entrepreneurial and digital growth across tourism, agriculture and urban landscapes.

Thanks to these programmes and to the increasingly popular spirit of entrepreneurship in the Kingdom, dozens of newly-founded startups have gained a foothold in the Cambodian market. A small team of Khmer engineers launched Koompi, a homegrown laptop distinctive for its open-source platform, at the tail end of 2018; in a matter of months, the startup has already sold over 1,000 laptops in the Kingdom and is now eyeing expansion into Myanmar. Demine Robotics, the brainchild of a group of young Cambodians fresh out of college, won recognition at a regional competition last year for its small, battery-powered robot capable of safely excavating unexploded ordnances. Both CamboTicket and BookMeBus found success a couple of years ago when they became the first Cambodia-based startups to digitise online bookings for trips on buses and vans.

Even so, the Kingdom has a long way to go before it can fully embrace the tech-spirit of its young entrepreneurs; though the government set forth a plan to foster a thriving digital economy by 2023, the Minister of Economy and Finance Aun Pornmoniroth announced days before the Digital Cambodia conference that it would take more than a decade for the economy to be truly technology-driven, as reported by the Phnom Penh Post.

Pornmoniroth explained that the government aimed to develop a long term policy – the particulars of which he did not share – that would serve as an effective guide to developing the digital economy as a whole. He added that Cambodia will likely not be home to $1 billion startups in the next few years, but the goal is to encourage a robust digital environment that has potential to foster continued growth of the startup scene.

On this point, Sopheap said he was in complete agreement.

“We want to show that Cambodia can be a startup destination for businesses that want to access the Asian market – from China, Europe and the US, as the case may be,” he said, discussing his plans for the Kingdom’s digital future. “It’s easy to live here, and businesses can release their prototypes and fine-tune their apps and business models here in the Kingdom before launching to the rest of the region.”

A small fish in a big Southeast Asian pond

The startup ecosystem across Southeast Asia is healthy and thriving, according to a recent report released by tech media platform e27. In 2018 alone, more than $17.9 billion in funding was raised in support of the region’s startups.

But Cambodia remains a budding ecosystem in relation to its neighbours; with a smaller population and economy, the country has yet to emerge as a significant player in the regional startup scene.

There are several reasons for that. Some of the most glaring issues standing in the way of Cambodia’s digital startup growth are a lack of coordination between Cambodia’s ministries, a nonexistent governmental policy on startups, a wide skills gap among the country’s young population, and limited access to regional networks and funding for local businesses.

It is not just a matter of addressing these issues to encourage economic growth: if Cambodia doesn’t take significant action to counteract the rise of the digital revolution, its passivity could spell its economic ruin. Cambodia, which depends heavily on its manufacturing industry, is particularly susceptible to the negative effects of “Industry 4.0” – a shift toward factory automation that could see up to 60% of unskilled jobs lost in the next five years, according to the International Labour Organisation. Cambodia needn’t wait five years to see the loss of jobs as a result of digitisation, Sopheap added, as manufacturers in the country’s booming garment and textiles industry have already begun installing machines that make unskilled labourers obsolete.

To counteract these alarming effects, Cambodia can look to its neighbours – many of whom have already begun tackling the rising tide of a digital transformation – to model its own approach.

Vietnam’s Diversifying Economy

In the face of rising digitisation, Vietnam has somehow molded itself into a manufacturing hub that continues to expand even as much of the world sets forth plans to deindustrialize their own economies, adding 1.5 million jobs to its manufacturing sector between 2014 and 2016.

Cambodia’s eastern neighbour has benefitted from the rising production costs in China, attracting manufacturers with its low-cost labour and relatively low cost of doing business. It has embraced open trade and invested heavily in its human capital and infrastructure with direct public investment in power generation, transmission and distribution, powering on even as Cambodia’s capital suffers daily power cuts.

Nonetheless, Vietnam’s manufacturing sector faces the same problems that are already looming on the horizon for Cambodia; rising wages and digitisation will soon encourage the dissipation of low-skill, labour-intensive industries, and millions of jobs could soon be lost.

The key to Vietnam’s success will be the diversification of its economy, which government policies have encouraged for years. The country’s 2013 Master Plan on Economic Restructuring has helped grow its services sector; the country’s E-commerce Master Plan has helped grow its internet technology industry; and the country’s IT Master Plan has given tax incentives to build education infrastructure and support new ICT firms and investment.

As a result, the Vietnamese digital scene is already thriving. There are training centres and tech parks for IT programmers and engineers scattered across eight cities, and its booming internet economy is expected to reach $33 billion by 2025. “Digitising the economy is a policy revolution,” Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng, Minister of Information and Communication in Vietnam, told a local news outlet earlier this year, “Rather than a technology revolution.”

Loosening Regulations in Thailand

Thailand has taken a slightly different route from Vietnam, remaining largely focused on changing its governmental policy to ensure its manufacturing economy is left in the past. In 2010, more than 40% of Thailand’s gross domestic product was in manufacturing, with the bulk of the country’s profits reaped from the garment and textiles industry.

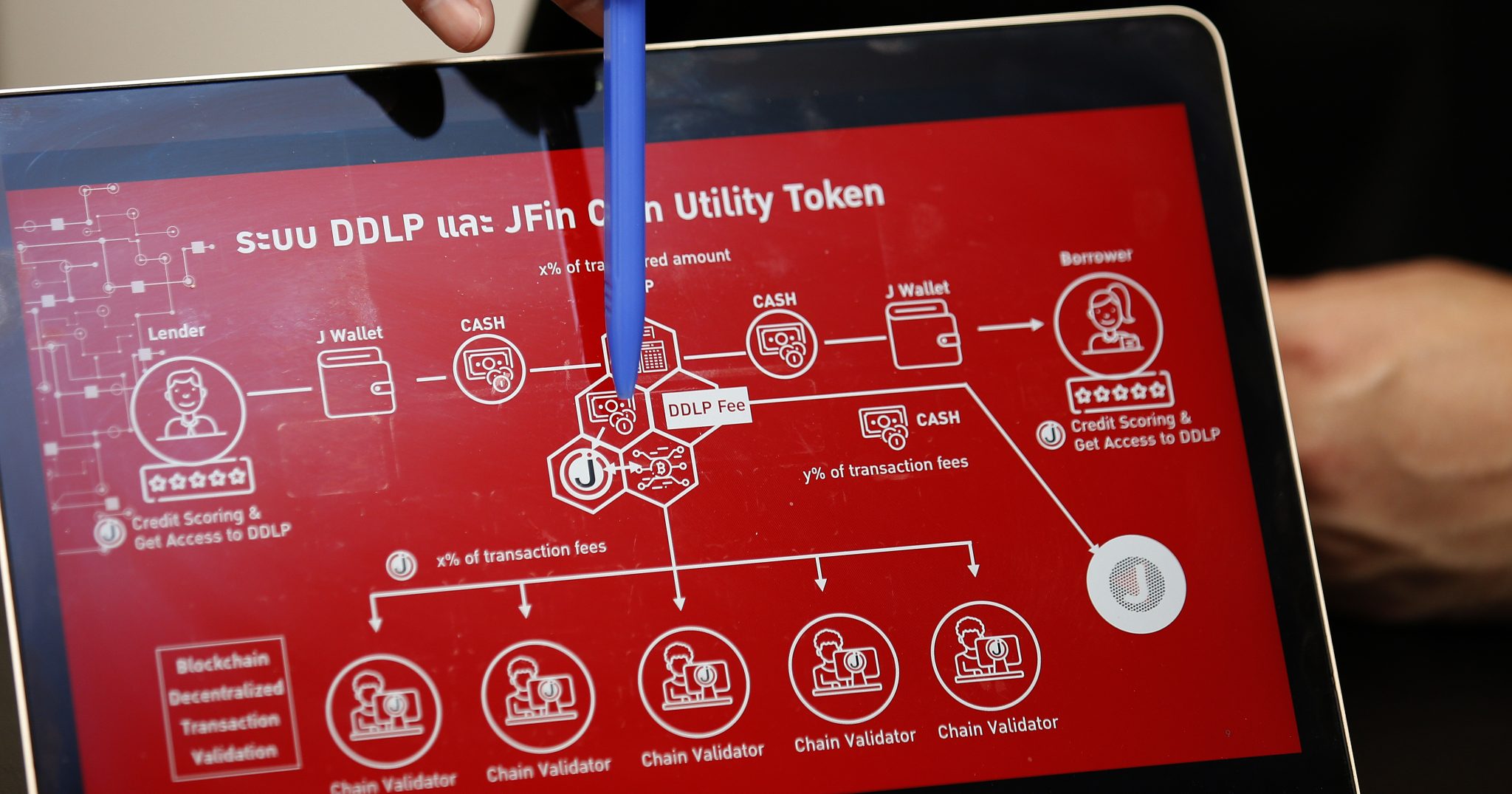

In 2016, the government set forth a strategy intended to create a new, tech-driven economy, and the ambitious 20-year plan has already had a strong impact on the country’s cryptocurrency and blockchain industries. At the same time that Thailand has legalised crypto trading, approved four major cryptocurrencies, begun issuing blockchain securities and opened its own initial coin offering platform, Cambodia’s government remains undecided as to how or if it will regulate (or even overtly legalise) use of cryptocurrencies.

Crypto and blockchain technologies are admittedly in their infancy and notoriously turbulent; even so, Thailand has worked to make itself attractive to new-age startups and businesses working in these spheres, staying ahead of a rising digital trend. The Thai government has also invested over a billion dollars in funding for local entrepreneurs, with an aim to foster over 3,000 startups within the next decade.

“Industry 4.0 is coming”

Manufacturing accounted for a hefty 31% chunk of Cambodia’s economy in 2016, and the country has yet to shift its focus away from at-risk unskilled labour. Cambodia could take a page out of Thailand’s book and begin moving away from manufacturing altogether, or follow Vietnam’s example and do its best to diversify its economy even as it maintains jobs in its garment and textiles factories.

As of now, the country’s approach remains unfocused.

In September last year, Ministry of Economy and Finance undersecretary Phan Phalla admitted that Cambodia is facing a long list of challenges as it realises the need for digital-friendly policies, a skilled labour force and a “mindset change” to prepare for the coming digital revolution.

“Preparing for the digital economy and responding to the fourth industrial revolution is one of the major priorities of the Royal Government in the next mandate,” he told a local news outlet. But no new mandate has yet to come to fruition, and although Cambodia’s officials promise change, the Kingdom remains at risk to the rising tide of “Industry 4.0” and the new technologies associated with it.

“We need to understand what the threat actually is, so we can determine how to respond to it,” Sopheap said.

He touted the Digital Cambodia conference as a prime example that the Cambodian government is finally paying attention.

“For the first time, technology has become a priority in the government,” he said. “Now more than ever, decision makers understand that Industry 4.0 is coming.”