On the river island of Koh Srolav in southern Cambodia, everything changed for the 300 or so families inhabiting the small fishing village about ten years ago, when the sand dredging barges arrived. Operating in the dark of night, they have plundered the Tatai river with little concern for the destruction they sow, safe in the knowledge that exporting the excavated sand to foreign governments – such as Singapore’s – and local developers would likely bring handsome rewards. As they scraped up mountains of silty sand from the riverbed, the fish deserted, once-plush mangroves were drained of life and the villagers’ fishing equipment was left in tatters.

In dire straits, the locals began taking out small microfinance loans to sustain themselves. Leak Sopheap, the community’s representative, told Southeast Asia Globe that up to 90% of families had taken out microloans in a bid to improve their lot. But, without the necessary economic conditions to increase their incomes, the families had instead fallen further into debt.

“Most of the families with loans are struggling to pay them back as it’s difficult to earn enough money from fishing now. Some have had to sell the fishing equipment they bought with the initial loan to try and pay back their debt,” she explained. “Some have even resorted to taking out second loans to try and pay back the first.”

The social entrepreneur Mohammad Yunus first introduced microfinance in the 1970s to help inject much-needed capital into struggling rural communities in Bangladesh. Predominantly centred on offering small, short-term loans to the poor at high interest rates, the novel approach to development was touted as a financial innovation that could lift millions out of poverty. Yunus even won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006.

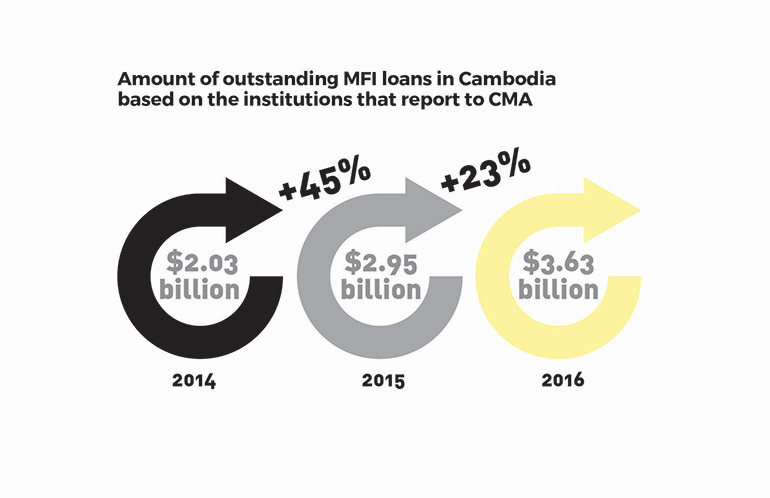

But as microfinance developed into a multi-billion dollar industry, the fragile alliance between the financial and the development worlds has been thrown into sharp relief, especially in Cambodia, where the amount of outstanding loans provided by microfinance institutions (MFIs) increased from $916.3m in 2011 to $3.63 billion in 2016 – a significant sum for a population of just over 15 million people.

“It seems that these MFIs have a plan to take advantage of the people”

Hun Sen, Prime Minister

“It seems that these MFIs have a plan to take advantage of the people,” Prime Minister Hun Sen lamented at the National Summit on the Development of the Microfinance Sector in Cambodia in March last year. “Which MFIs are doing this, and why haven’t we taken action?” he later asked the crowd, citing examples of people’s homes being taken from them after they failed to pay back their loans.

Since then, with one eye on the upcoming commune elections in June, the increasingly populist leader has been eager to be perceived as a champion of the poor, locking horns with what he has portrayed as a mercenary, opportunistic industry.

First came the ostensibly independent National Bank of Cambodia (NBC)’s order on 15 February 2017 that all financial institutions would need to visibly declare that they were a ‘private institution’ and not state-owned. The NBC said in an announcement that the decision was made because it had “observed that there are some bad people who do propaganda by cheating the public, and who say that financial institutions in Cambodia are state-owned institutions, telling borrowers that they are not required to repay their debts”.

Then came the government’s call for certain banks to change their logos to help differentiate themselves from government ministries. Among those forced into a rebranding exercise – at a cost of $3.5m – was Cambodia’s largest commercial bank, Acleda, whose mythical bird insignia was said to be too similar to the Ministry of Economy and Finance’s logo.

And finally, on 13 March 2017, the NBC delivered the killer blow. From April onwards, it announced, the entire microfinance sector would be subject to an interest rate cap of 18%, an amount that analysts said would make the majority of MFI loans loss-making activities.

While he said it was too early to assess the full extent of the interest rate cap’s impact on the sector, Yun Sovanna, general secretary of the Cambodia Microfinance Association (CMA), said that all MFIs would have to reassess their business models and strategies.

“Going down to remote areas and offering small loans to people with low incomes has huge operational costs – for some MFIs, these costs alone can be [equal] to 20% or 30% [of interest]. Continuing to operate like this under an 18% interest rate cap would not make business sense,” he said. “MFIs will have to completely re-evaluate their

business model.”

Ultimately, analysts say, it is the poor – the intended beneficiaries of the interest rate cap – who will be hit the hardest as MFIs will no longer be able to afford to provide the small loans that this demographic requires.

“The big problem in Cambodia has been loan refinancing… All of a sudden, a client that started with a $500 loan now has a $1,000 loan, which is far too much debt for them to be able to repay.”

Daniel Rozas

The move could also affect the interest rates offered to customers that have savings accounts with MFIs as the institutions look to cover their losses. This could have wider ramifications for the industry, according to Daniel Rozas, a microfinance consultant that helped establish the Microfinance Index of Market Outreach and Saturation (Mimosa).

“I imagine that they would push the deposit interest rates lower, which would create the extra margin on the loan portfolio size. That hurts the savers, which is not what you want,” he said. “The last thing you want to do is discourage people from saving or encourage them to save abroad.”

Nevertheless, Anton Simanowitz, director of the consultancy Social Performance Solutions and author of The Business of Doing Good, a detailed case study of the Cambodian MFI Angkor Microfinance Kampuchea (AMK), said that while the cap was “a populist move driven by the elections” that he believed would bring a lot of negative impacts to clients, the experience in other countries suggests that the “MFIs would most likely continue to operate reasonably well”.

“In other countries where an interest rate cap has been introduced, MFIs have found ways to maintain the same income by replacing interest with fees [such as] administration charges, processing charges and service charges, or by increasing charges on unregulated products [such as] credit life insurance… this is likely to be the case in Cambodia,” he wrote in an email.

On 23 March, Hout Ieng Tong, the current chairman of the CMA, told reporters that the NBC had “agreed in principle” to reduce the annual licence fee of affected MFIs and to offer riel-denominated loans directly to lenders to make it feasible for MFIs to continue operating with the interest rate cap in place.

While the cap is likely to damage the profitability of MFIs, greater regulation is necessary. The rate at which the sector had grown up until 2016 had, by all accounts, been unsustainable. As more players moved into the market, enhanced competition increased pressure on MFIs to take risks and offer greater loan sizes to customers in a bid to capture their business.

“The big problem in Cambodia has been loan refinancing, where, let’s say I have a loan with an MFI, and then a new MFI comes to me and says: ‘Listen, I’ll give you a bigger loan than you currently have and you can repay that first loan and become my client instead.’ All of a sudden, a client that started with a $500 loan now has a $1,000 loan, which is far too much debt for them to be able to repay,” Rozas explained.

A circular produced by Mimosa in June 2016 demonstrated that loan sizes in Cambodia had, in fact, grown four times faster than client incomes between 2003 and 2014 – from 54% to 220% of per capita gross national income.

But after the International Monetary Fund voiced its grave concerns over the Kingdom’s explosive credit growth in a 2015 report, the NBC began to introduce policies aimed at reducing the amount of lending by MFIs. As a result, the Kingdom’s credit growth had already slowed to 23% in 2016, down from 45% in 2015.

While Sopheap’s distressing tale of a village trapped by insurmountable debt is not unique in Cambodia, the full extent of over-indebtedness in the Kingdom is still unknown. What’s more, the share of loans overdue more than 30 days, or the ‘portfolio at risk’, remained a respectable 1.41% in 2016, bringing into question Hun Sen’s motive for introducing the cap.

But the cap also brings with it opportunities. Not only does it make the industry ripe for consolidation – with Hong Kong’s Bank of East Asia and Sri Lanka’s LOLC already acquiring a majority stake in Cambodia’s largest MFI, Prasac Microfinance since the announcement – it may also benefit the financial technology industry.

In a report released before the interest rate cap had been announced, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) argued that low bank account usage together with increasing smartphone penetration meant Cambodia’s banking sector “could boost GDP by 6%” if it sped up its integration of financial technology, or fintech. This would equate to a 30% increase in income for those earning less than two dollars a day.

Fintech, such as branchless banking and mobile banking, dramatically reduces operational costs by reducing the need for staff to travel to remote areas or decreasing the costs associated with excessive paperwork. Given that the interest rate cap will require MFIs to reduce their costs, many could therefore turn to local companies such as fintech startup Morakot and mobile payment provider Wing as they strive to remain competitive in the years to come.

Acleda bank has already begun tapping into the myriad opportunities fintech offers MFIs. Recognising that large swathes of microloan repayments are made through remittance payments, the bank made it possible for Cambodians without bank accounts to send and receive money via their Unity ToanChet mobile application. Those without bank accounts are sent one-time passwords in a text message, which they can then use to withdraw money from ATMs.

“Fintech is very important for financial institutions, but [firstly] we must familiarise people with the technology,” So Phonnary, Acleda bank’s executive vice-president told Southeast Asia Globe. “We develop fintech to make banking and microfinance more convenient to our customers.”

Yet adopting fintech takes time and money – luxuries that many smaller MFIs do not possess, according to Sovanna. “Innovations in technology could help, but it’s not the only remedy to the interest rate cap. The industry will have to apply many solutions,” he said. “At this moment, I think that many MFIs do not have the capital to invest in technology and mobile banking, even though it is in their long-term interest.”

But as it does away with “the personal contact that allows for good lending”, Simanowitz warned against the sector hedging its bets on fintech. MFIs make up a significant section of the country’s banking industry so, whichever path the sector takes, the new direction is likely to have far-reaching consequences.

Whether or not the government will listen to what the industry is saying is another matter entirely; the fact that it implemented the cap even after the NBC had publicly derided the policy in November suggests it will not.

“Just as a healthy person doesn’t go to the doctor, a rich person doesn’t need loans from microfinance institutions,” said Bun Mony, former chairperson of the CMA. “That’s why they don’t properly understand their importance.”