When on February 12, 2019, the EU announced it had started the withdrawal procedure for Cambodia’s Everything But Arms trade privileges, reactions ranged from the defiant (EBA withdrawal provides ‘opportunity for growth’), to the nonchalant (EBA Withdrawal Does Not Concern Me … PM Hun Sen), and the catastrophic (Losing EBA a “disaster” for Cambodia).

What few would have predicted, however, is that when the decision was finalised exactly one year later – partially withdrawing the Kingdom’s duty-free access to the 27-member EU bloc, slapping tariffs on $1 billion in goods – it would be far from the worst development for the Cambodian economy in 2020.

As the tides of the global Covid-19 pandemic have swept the Kingdom since February, the government has been left to scan its battered economic landscape for explanations and solutions. Wading through the damage, one clear conclusion becomes apparent: Cambodian workers have long been vulnerable to external forces beyond their control.

“One thing is certain [about the future], your job will never be the same,” was the prophetic message to Cambodian workers from Bora Kem of Mekong Strategic Partners as he sat in a recording booth last week for the Globe’s podcast Anakut.

Indeed, a low-skilled workforce largely concentrated in the tourism, garment, construction and agriculture sectors, the International Labour Organization estimated in 2017 that 57% of all Cambodian workers – some four million jobs – faced a high risk of automation, while in textiles, clothing and footwear this was as high as 88%.

Automation remains yet to meaningfully displace Cambodian workers. But the shuttering of factories, downing of tools and closing of borders in recent months has given the government and people a taste of what was once a distant, hypothetical future where workers are laid off en masse.

With the pandemic’s cautionary tale bringing the fragilities of an unskilled and undiversified economy firmly into the present, the multi-billion-dollar question now facing Cambodian stakeholders – from the government, to the private sector, CSOs and workers themselves – is, what should be done next?

In neighbouring Mekong countries, preparations for embracing Industry 4.0 – the term describing the emerging Fourth Industrial Revolution, in which manufacturing and industry gears towards technological innovation – have firmly begun.

In Thailand, as the country’s youth take to the streets demanding political revolution, in the nation’s ministries, they are attempting to engineer an economic one.

Since the launch of Thailand 4.0 in 2016, grand visions have the country looking to establish itself as the region’s leading high-tech manufacturing hub – an innovation-driven economy harnessing the widespread adoption of robotics.

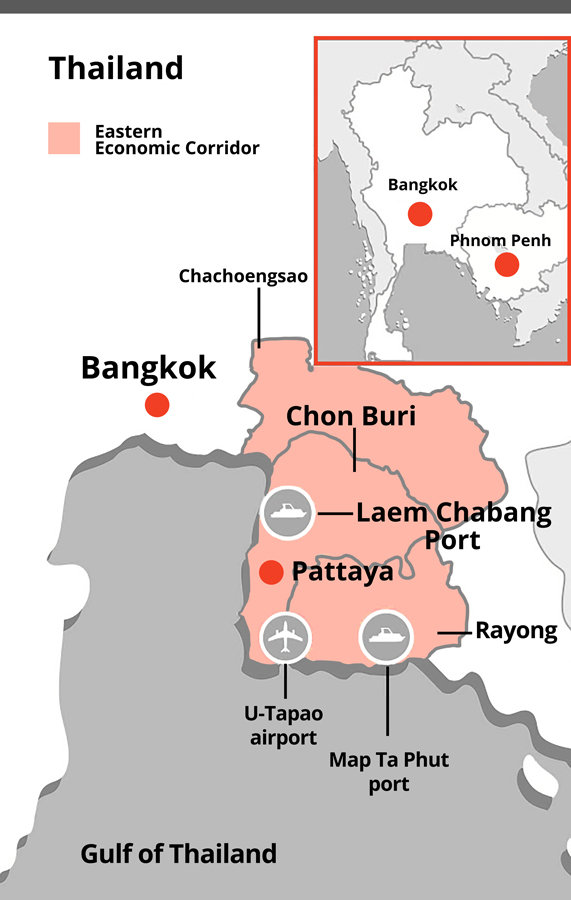

At the heart of this economic revolution is the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), a special economic zone covering 5,000 square miles across eastern Thailand’s Chachoengsao, Chonburi and Rayong provinces. Populated by a growing cohort of cutting edge automotive and electronics operations, the region is set to receive $45 billion in investment to develop smart cities, technology parks and transport links.

Heavy tax breaks and financial incentives to lure companies “using advanced technology and innovation, or conducting R&D activities” to areas like the EEC show the government’s intent to realise their Industry 4.0 aspirations.

In Vietnam – a country emerging from the low-skill manufacturing bind that Cambodia now finds itself, moving up the value chain to become a burgeoning low-cost electronics hub – the vision for Industry 4.0 is similarly aspirational.

In 2019, Vietnam’s Ministry of Planning and Investment released its draft national strategy on Industry 4.0, aiming to transform Vietnam into a digital society over the course of the next decade. That year, the country also launched its grammatically suspect, but economically sound, ‘Make in Vietnam’ drive seeking to establish 100,000 tech firms in the country by 2030.

Moving towards this goal, in June this year, the country’s prime minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc signed Decision 749/QD-TTg. An ambitious national programme on digital transformation with lofty targets set for 2025, the Decision also aims to see Vietnam enter the world’s top 50 countries for IT development by 2030.

Beyond broad goals for digital literacy, still needed is a clear idea about just what the Kingdom’s own Cambodia 4.0 or Make in Cambodia strategy could look like

Back in Cambodia, while discussions have begun, it would seem the government is still working to define a clear strategic direction and vision to harness the benefits of Industry 4.0.

Regular references are made to the benefits of harnessing technology in the Kingdom’s economy, with various government reports in recent years laying out Cambodia’s Industry 4.0 aspirations. This includes, among others, the National Strategic Development Plan (NSDP) 2019-2023, in which the government states its aim to “prioritiz[e] the development of human resources in science, technology and innovation”, develop education and training programmes dedicated to digital technology, as well as foster “entrepreneurship and digital ecosystems”.

The strong emphasis on human resource development is no accident, with Cambodia currently possessing poor digital literacy levels compared to its regional peers. The Kingdom ranked the lowest in Southeast Asia, and among the lowest globally, in the 2020 Global Talent Competitiveness Index – an annual ranking of countries based on their ability to develop, attract and retain talent suited to the modern economy.

But beyond broad goals for digital literacy, still lacking is a clear idea about just what the Kingdom’s own Cambodia 4.0 or Make in Cambodia strategy could look like in practice.

“Both in the Rectangular Strategy [for Growth, Employment, Equity and Efficiency in Cambodia] and the Industrial policy [Cambodia Industrial Development Policy 2015 – 2025], there is no clear, specific policy that focuses on promoting Industry 4.0,” Chandarany Ouch, a national economist at the United Nations Development Programme in Cambodia, told the Globe in a recent interview.

Just who will lead the charge towards Industry 4.0 also remains unclear, with UNDP stating in their August report Adaption and Adoption of Industry 4.0 in Cambodia that “no ‘champion’ has clearly emerged promoting its [Industry 4.0’s] adoption in Cambodia”.

Perhaps the Ministry of Industry and Handicraft has aspirations to fill this role, as its bid to change its name to the Ministry of Industry, Science, Technology and Innovation was successful in January. But it remains to be seen whether this rebranding is merely cosmetic or will result in meaningful operational change within the Ministry’s walls.

In his role as Youth Employment Project Coordinator at UNDP Cambodia, Virak Nuon is part of a wider effort to foster an Industry 4.0 culture in the Kingdom. Through collaboration with colleagues from UNDP Accelerator Labs, Nuon works with the government in an effort to prepare the next generation of Cambodians for the challenges of the fast-evolving economic landscape around them.

He too recognised that while Industry 4.0 has become firmly part of the national conversation, a concrete vision about how this could manifest still needs refining.

“In terms of overall consideration it’s there in the policy, and the term Industry 4.0 has been mainstream across documents,” he told the Globe. “But when it comes to specific indicators, there’s none that really address Industry 4.0. We need more specific indicators to work towards.”

The lack of concrete movement on Industry 4.0 in Cambodia, at least compared to regional neighbours, may be reflective of a concern from the government about whether to fully embrace the changing state of play around them.

Afterall, ushering in digitalisation and automation can seem a counterintuitive move in a country where large swathes of the population are out of a job should technology be introduced that is able to undercut their labour.

“What I’ve observed in the country is that we have not decided whether Cambodia should prioritise Industry 4.0. It is something that has been argued about, whether we go for I.40 or put it off for a while and go after lower-hanging fruit in Cambodia,” said Virak.

The temptation to go after low-hanging fruit has only grown in recent months, with the government pivoting towards what Chandarany calls a “survival strategy” in which the promotion of Cambodia’s old faithful, agriculture, has been central to keeping the economy going during the pandemic.

We can’t promote agriculture based on traditional methods, we have to bring in technology, and make it more productive

Back in July, Prime Minister Hun Sen said that Covid-19 provided an opportunity for Cambodia to “dominate in the agricultural sector”, redirecting funds towards it to help offset some of the damage done to other parts of the economy.

Once the Kingdom’s top earner, now an innificient sector ripe for innovation and revitalisation, for Chandarany, Cambodia returning to the fields could still offer a path towards Industry 4.0.

“Even if we focus on growing the agriculture sector for now, it is still important to promote technology in the sector,” she said. “We can’t promote agriculture based on traditional methods, we have to bring in technology, and make it more productive.”

Whatever route Cambodia decides to go down – whether that be greater automation in manufacturing or tech-driven agriculture – a flexible and adaptive workforce seems to be the name of the game in Industry 4.0.

“The demand for advanced cognitive skills and socio behavioral skills is increasing, whereas the demand for narrow job-specific skills is waning,” stated a January report on Cambodia’s garment sector by German political foundation Konrad-Adenauer Stiftung. “This combination of specific cognitive skills (critical thinking and problem-solving) and socio behavioral skills (creativity and curiosity) is transferable across jobs.”

In essence, this means training-up young people so they are prepared for whatever comes their way – a tech-savvy next generation of Cambodians ready to turn their hand to whatever the market demands. Back in the Globe’s Phnom Penh recording booth last week, this was a message Bora Kem was keen to hammer home.

“[We should] not teach out people how to memorise facts and figures, but to really teach them how to change, how to be adaptable,” he said. “One minute it’s garment factory workers, the next minute you have to make car parts, or a completely different job.”

This story is the first in a series produced in partnership with UNDP Cambodia, which will, over the coming months, aim to drive national dialogue on the future of innovation, youth employment and skills development in the Kingdom.