Me Me Khant, from Yangon, doesn’t know when – or even if – she’ll ever see her mum and dad again. When Myanmar’s military, known as the Tatmadaw, deposed the country’s democratically-elected government on February 1, the 25-year old Khant was studying at Stanford University, in California.

Because her mother was politically active and hunted by the Tatmadaw, her parents went into hiding.

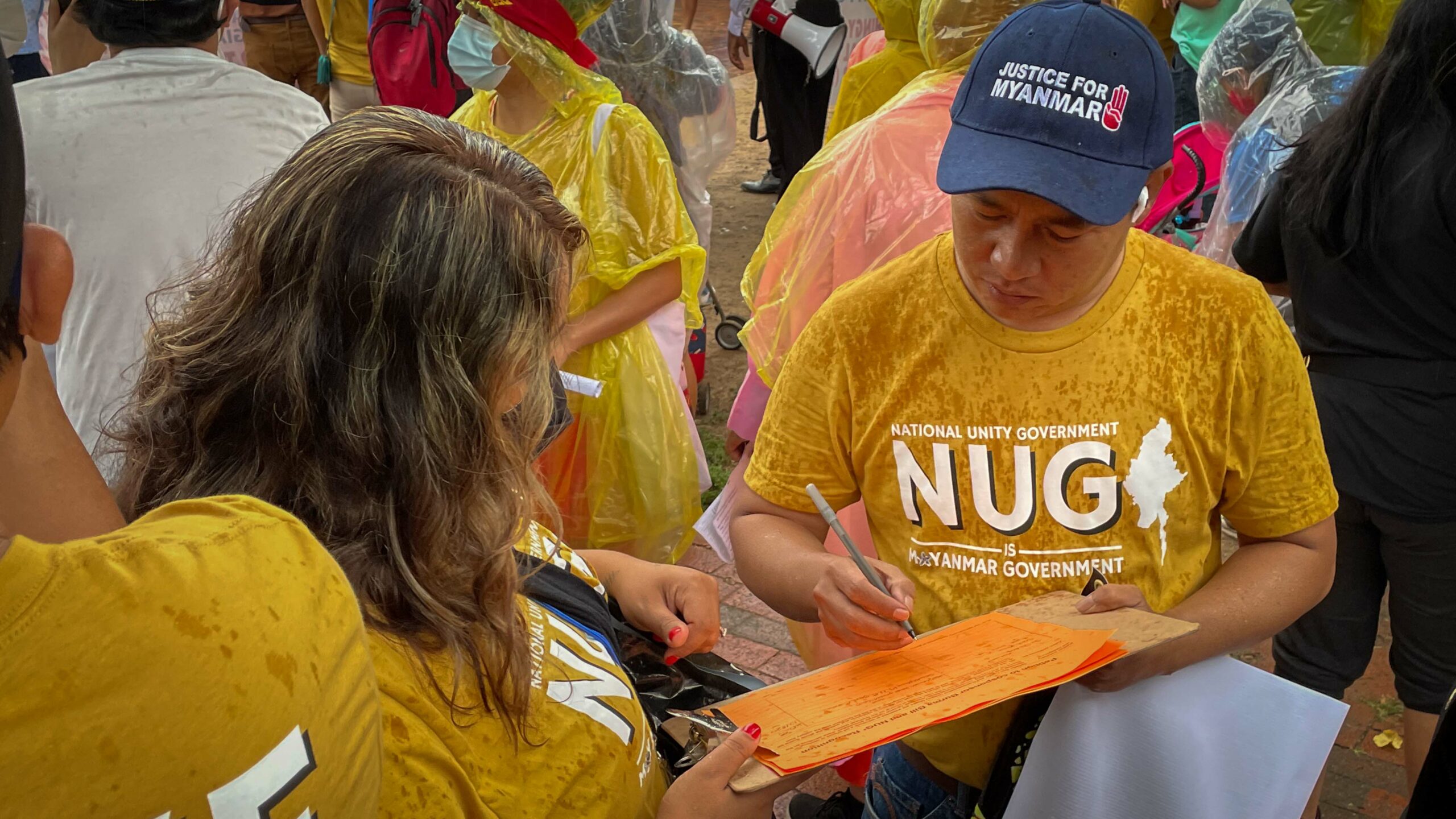

“I can only communicate with my mother every three weeks,” Khant said, wearing a face mask on August 7 as she braved the rain. Standing in front of democracy symbol the White House in Washington DC, she marched among a flurry of flags representing the diverse stakeholders that form Myanmar’s anti-junta, pro-democracy movement.

With her mother and father trapped in Myanmar, Khant decided to fight the junta by helping to organise a political campaign asking the US for support in restoring the country’s civilian leadership.

She belongs to a patchwork of activists in the US – individuals and non-governmental organisations calling themselves collectively the US Advocacy Coalition for Myanmar – that since the coup have been urging the country’s lawmakers and government officials to pass a law nicknamed the “Burma Bill”.

While details remain scant, if activists were successful the law would likely place sanctions on the Tatmadaw’s international income and pave the way for official recognition of Myanmar’s remnant civilian leadership, the National Unity Government (NUG). Crucially, if it were to be passed and the NUG recognised as Myanmar’s legitimate government, this would also free up $1 billion in frozen assets linked to the military regime, a vital source of revenue which the provisional government says would be redirected towards vaccines and displaced people among the country’s beleaguered population.

Last Saturday they staged demonstrations in San Francisco, Boston and a 2,000-person strong march in Washington DC from the White House to the Congress. The “Save Myanmar March” was the public side of their lobbying efforts to get the Burma Bill passed.

As it began to rain in front of the White House, Khant and other demonstrators crowded around a number of speakers who shouted through a microphone sometimes addressing supporters and sometimes calling across the street to the White House.

“President Biden, please help Burma! US Congress, please help Burma!”

Activists had, in the weeks leading up to Saturday’s demonstrations, targeted their advocacy to 31 senators who they asked for personal meetings to present their policy recommendations and advocate for them to be included in the bill currently being drafted by Senate staff.

“We have meetings set up with about half of the senators’ staff, but they’re all online because of Covid,” explained Khant.

Another one of the activists present on Saturday, Arkar Kyaw, had participated earlier in the week in a video call with the office of Sen. Marco Rubio, a Republican from Florida and a leading member of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

“They said, they are sorry and that nobody deserves to go through this kind of atrocities, but they didn’t promise to accept our requests,” said Kyaw.

Kyaw also reported that Rubio’s staff concluded their meeting by saying the Senator would coordinate with Sen. Ben Cardin of Maryland, a Democrat who is likewise on the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. According to activists, a legislative assistant on Cardin’s staff is rumoured to be drafting the text of the bill.

Together with the Coalition, activists like Khant and Kyaw have been targeting lawmakers from both parties. Their hope is that bipartisan support for the Burma Bill will raise its chances of being swiftly passed.

One of the activists’ main requests is for the US to cut off the Tatmadaw’s sources of international income. This is a policy position shared by six senators, including Rubio, who published a public letter dated April 27 stating gas revenues from Total and Chevron were the largest source of foreign exchange for the Tatmadaw and helped the junta in Myanmar to survive international sanctions in the 1990s.

Days after the coup in Myanmar, US President Joe Biden issued Executive Order 14014 freezing $1 billion held in an account at the US Federal Reserve Bank normally used by the Central Bank of Myanmar. Now, demonstrators urged using this money to pay for everything from the salaries of NUG officials to guns for anti-coup militia forces in Myanmar.

“We need to build up the PDF, the People’s Defense Force. We have to fight for it. We can’t just talk with evil,” said Tin, who gave only his first name because of safety concerns for his relatives in Yangon. He drove eight hours to protest in Washington DC from the US state of Michigan.

Speaking with the Globe last Friday outside of Washington DC, US-based Htin Linn Aung, Minister for Communications, Information and Technology for the NUG, pledged to spend the money improving the lives of the people in Myanmar. He said the NUG would, among other things, direct funds to non-governmental organisations on the Myanmar-Thai border who are already purchasing goods with international aid funds and transporting them into Burma, as the Globe previously reported in March.

“There are one billion dollars that were seized by the US government. That should be released to the NUG,” he said. “We can purchase a lot of vaccines. We can purchase a lot of goods for the people. Right now we have about 200,000 internally displaced people, we can help them with food, shelter, everything.”

It’s dirty money. It isn’t clean money. [Chevron] should not do that. They are funding evil people

Although a legislative assistant in Cardin’s office is rumored to have already included general sanctions in a draft of the Burma Bill, activists want specific wording that would target the Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE), an agency within the Myanmar government’s Ministry of Electricity and Energy.

Gas revenues owed to the MOGE from joint ventures involving corporations such as US-based Chevron, France-based Total, and Thai-owned PTT are estimated to total approximately $1.1 billion each year according to calculations by Reuters.

In the April 27 letter, US senators recommended placing sanctioned MOGE funds into a trust or protected account that could be used by a democratically elected Myanmar government.

“It’s dirty money,” said the activist Hnin Lwin who came to Washington for the demonstration. “It isn’t clean money. [Chevron] should not do that. They are funding evil people.”

Lwin, who now resides in California, fled Myanmar in 1988 after participating in that year’s sweeping pro-democracy protests, which were crushed with force by the Tatmadaw. She has already participated on video calls with staff from the two senators from California telling her personal story and asking them to support the Burma Bill. Lwin said she still has a guilty conscience because while she escaped, many of her friends were imprisoned by the military.

“I have to do something. If we don’t do enough this time, one last time, then the problem will just be passed on again to the next generation.”

Activists from the Coalition have also been urging the US to formally recognise the NUG as Myanmar’s “only legal and legitimate government”, as phrased in a policy paper submitted to lawmakers.

“We asked them to recognise the NUG because that would improve public trust [in the NUG],” Kyaw said, adding that Rubio’s staff said they would seriously consider co-sponsoring the bill.

“The NUG is working towards being a more ethnically diverse government including the Rohingya.”

While Congress can include recommendations in a law, only the president has the authority to formally recognise other governments. This recognition often carries much more than just symbolic meaning.

For example, the Obama administration In July 2011 recognised the National Transitional Council (NTC) in Libya as the official government of the country after the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi. This not only boosted the NTC’s diplomatic work with other countries around the world, but also allowed the council to assume control of assets that had been frozen by sanctions.

But President Joseph Biden is proving to be even more reluctant than his predecessor Donald Trump to entangle the US in conflicts around the world. On Tuesday, the US State Department announced $50 million in humanitarian assistance for Myanmar, suggesting the US would rather provide aid to the people of Burma this way rather than by recognising the NUG and releasing to them the $1 billion in frozen funds.

The rise of authoritarianism is not only in Myanmar and Asia. It’s in America too, especially considering what happened in January

The next step is for a member or group in the Congress to formally submit a bill to either the House or Senate. Afterwards a bill is then debated, possibly revised, passed by a vote and then sent to the president for his signature if he agrees.

Despite the Save Myanmar March and calls with officials, legislators have offered few signs they will include activists’ requests in a Burma Bill. On the day of the demonstration, Cardin stated on Twitter that he supported “human rights and democracy in Burma”, but made no mention of sanctions, the NUG or even a bill in the works.

Any timeline for the bill is unclear and, for now, rests on informal statements from senators’ offices. Khant told the Globe she was told by staffers of Sen. Alex Padilla, a California Democrat, that senators will introduce a bill when they return to session on September 13.

On Saturday, as Myanmar nationals asked US leaders to support them in their fight for independence from the Tatmadaw, they stood in LaFayette Square, named to honour a Frenchman who helped American colonists win their independence against the British.

Marquis de LaFayette first travelled to the US in 1777, fought in the army, was wounded and returned to France to raise funds to support the American War of Independence, which led to the founding of the country. Many US historians believe that without support from France, those early colonists would not have been successful.

Just as LaFayette was critical to the founding of democracy in the US, others see the US as holding a continuing responsibility to support the people of Burma in their quest for democracy.

“The rise of authoritarianism is not only in Myanmar and Asia. It’s in America too, especially considering what happened in January [2021 US Capital Attack],” said Khant.

“That highlights the fragility of democracy and that the US needs to promote democracy more.”