On October 23, Joko Widodo, popularly known as ‘Jokowi,’ announced his long-awaited new cabinet as he began his second and final five-year term as president of Indonesia.

Made up of 38 ministers and 12 vice ministers, the cabinet’s bulk is attributable to the president’s desire to reward the array of political parties, prominent businessmen, and other political fixers who helped him win April’s presidential election.

Contradicting Widodo’s promises that his cabinet would be largely comprised of professionals he selected, the appointments are akin to a form of debt repayment, or hutang budi, for the array of political allies and campaign funders seeking reward for helping the president fend off the campaign challenge of Prabowo Subianto.

Prabowo’s elevation has been the subject of much criticism, with some observers describing it as typical of Indonesia’s elite-based coalition politics

The outcome is a cabinet coming primarily from the ranks of party bosses such as Golkar Party chairman Airlangga Hartarto, tycoons such as Erick Thohir and Nadiem Makarim, and retired military officers close to his campaign. Only a few familiar technocrats were appointed – such as Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati and Pratikno – the former president of Gadjah Mada University who is one of the president’s closest advisors.

Political parties affiliated with the winning coalition are the prime beneficiaries, indicating that leaders of Jokowi’s coalition – such as the Indonesian Democratic Party Struggle (PDIP) led by former president Megawati Soekarnoputri and National Democratic Party’s (Nasdem) Surya Paloh, had a say in the cabinet makeup, tying the president’s hands.

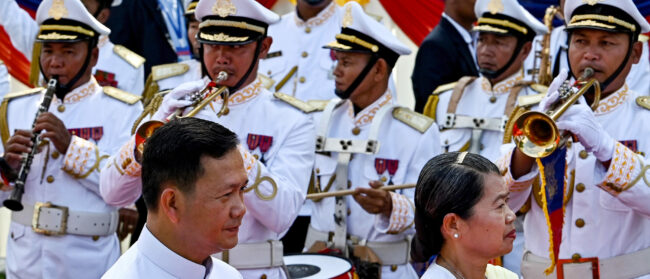

Indonesia’s Coordinating Political Legal and Security Affairs Minister Mahfud MD, Religious Affairs Minister Fachrul Razi, Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati, Foreign Minister Retno LP Marsudi, Coordinating Economic Minister Airlangga Hartarto, Coordinating Human Development and Culture Minister Muhadjir Effendy and Presidential chief of Staff Moeldoko, after being sworn in as ministers at the Merdeka Palace in Jakarta, 23 October 2019. Photo: EPA-EFE/Adi Weda

21 out of 50 appointees came from political parties, including the PDIP, the president’s own party, and the National Awakening Party (PKB) affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama – Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation, as well as Golkar and Nasdem.

While this is a normal outcome in most countries using a presidential system and featuring a ‘rainbow coalition’ of multiple parties clinging to the winner’s coattails – for instance in the Philippines or in most Latin American countries – many had hoped that Widodo would not end up appointing so many party and business leaders.

Widodo’s most controversial decision was his inclusion of Gerindra, the erstwhile opposition party led by Prabowo Subianto – his former rival in two consecutive presidential contests. The party received two ministerial appointments in the new cabinet – one of them given to Prabowo himself, the new Minister of Defence.

The president’s decision to include Prabowo in his ‘rainbow coalition’ cabinet seems to disregard the highly polarising and negative campaign assaults against Jokowi instigated by Prabowo and his supporters from the hardline Islamist camp. But the appointment showed that Widodo had quickly gotten over both Prabowo’s unproven accusations that the election was fraudulent and the May 22 riots in Jakarta by Prabowo’s supporters, during which ten people were killed and hundreds more injured.

Prabowo’s elevation has been the subject of much criticism, with some observers describing it as typical of Indonesia’s elite-based coalition politics, which perpetuates the dominance of an oligarchy that does not pay attention to the rest of the population.

Others discerned a signal that Widodo would disregard human rights, or at least not make those a priority during his second term, given long-standing allegations of Prabowo’s involvement in several high profile cases of human rights violations when he was a military officer during the reign of Indonesia’s ex-dictator Suharto,who was also Prabowo’s former father-in-law.

Observers have predicted any reforms proposed by new ministers could face resistance from well-entrenched bureaucrats

This was also indicated in the reappointment of the PDIP’s Yasonna Laoly as Minister of Law and Human Rights. Laoly was thought to be instrumental in the new laws that significantly weaken the authority of the Anti-Corruption Commission, a body known by the Indonesian acronym KPK. He also played a major role in proposed revisions of the Indonesian criminal code law that would have meant harsh punishment against anyone convicted of ‘defaming’ the president, the parliament, and other state institutions – and also would have criminalised virtually all forms of pre-marital sexual relations.

As a reaction to these unjust laws, university students have demonstrated throughout Indonesia from 23 September to this day. So far five students have been killed during the protests, with hundreds more injured or arrested.

Another group whose influence looks set to become more prominent compared to Widodo’s first-term cabinets is the business moguls who made significant contributions to his re-election campaign.

Two tycoons – Erick Thohir and Wahyu Sakti Trenggono – served respectively as the chair and treasurer of the campaign team. Thohir was the chairman of the high-profile 2018 Asian Games held in Jakarta and was owner of several sports clubs in Europe and the US, including Italian football giants Inter Milan. Both men were rewarded with cabinet appointments – as Minister of State Owned Enterprises and Vice Minister of Defence respectively.

Other tycoons appointed to cabinet include Nadiem Maskarim – founder of online ride-hailing company Gojek, as Minister of Education and Culture, communication tycoon Wishnutama Kusubandio as Minister of Tourism and Creative Economy, and Angela Tanoesoedibjo – daughter of media mogul Hary Tanoesoedibjo – as the Vice Minister.

Nadiem’s appointment seems to be in recognition of Gojek’s rapid rise. Now arguably Indonesia’s most recognisable e-commerce company, its value rocketed from US$1.5 billion in 2014 to US$10 billion this year.

On the other hand, Angela’s appointment has raised concerns regarding her father’s behind-the-scenes influence in cabinet selection, given that his MNC Media controls approximately three quarters of the free-to-air and pay TV markets in Indonesia. The appointment might represent an attempt to influence regulation of the country’s lucrative and growing media and telecommunications industries.

Widodo appointed Makarim as a reformist who could potentially transform Indonesia’s education system and promote new entrepreneurs from e-commerce and creative industries. However, observers have predicted any reforms proposed by new ministers could face resistance from the well-entrenched bureaucrats that have strictly regulated Indonesia’s education sector for the past few decades.

The declining influence of technocrats can clearly be seen in Widodo’s economic ministries, where long-term Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati is the sole appointee with a relevant professional background, having previously served in the Ministries of National Planning and Finance under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004 to 2010) and as a Managing Director of the World Bank from 2010 to 2016.

Other economic ministries, such as the National Planning and Trade portfolios, are held respectively by Suharso Monoarfa and Agus Suparmanto, all political party representatives. The Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs is Airlangga Hartarto, the chief of Golkar, the party machine set up by former dictator Suharto and which won 12.3% of votes cast in this year’s parliamentary elections.

The declining number of ministers from a technocratic background indicates the increasing dependence of Jokowi on party leaders and businessmen in economic policymaking. This might potentially undermine Jokowi’s commitment to have a ‘fully free hand’ in implementing economic and other policy reforms during his second presidential term.

The new cabinet also highlights the continuing prominence of the Indonesian security forces in running the country. Retired generals who served in Widodo’s first-term cabinets – such as his long-term associate Luhut Pandjaitan, now coordinating Minister of Maritime Affairs and Investment, and Moeldoko, the Presidential Chief of Staff – have been retained.

Luhut and Moeldoko have been joined by Police General Tito Karnavian – former head of the National Police – as the new Minister of Home Affairs. Fachrul Razi – another retired general with past postings in the intelligence service – is the new Minister of Religious Affairs.

The main casualty of Widodo’s desire to accommodate every party and group that contributed to re-election could be the ambitious economic reform agenda the president aims to implement

Luhut’s new appointment as the senior minister in charge of dealing with new foreign direct investment (FDI) – replacing the investor-friendly technocrat Tom Lembong – has spurred concerns that Luhut could increase his influence over the lucrative oil, gas and mining industries, sectors in which his company PT Toba Sejahtera Group would have a direct stake.

Deploying such senior military figures and retired police generals indicates that Widodo is aiming to secure and protect his second term from any potential disruptions – for instance from hardline Islamists responsible for the 2016/17 rallies against Jakarta’s Chinese-Indonesian governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, who lost his re-election bid and was sentenced for two years imprisonment for allegedly committing religious blasphemy.

These groups went on to become Prabowo’s staunchest supporters during his presidential campaign and have vowed to continue opposing Widodo – even after Prabowo joined the new administration. A recent statement by Tjahjo Kumolo – a former Home Affairs Minister who is now in charge of the Civil Service and Bureaucratic Affairs Ministry, declaring his ministry will ban civil servants from wearing full-faced veils (niqab) signifies the administration plans further crackdowns against hardline groups, particularly against those that have allegedly “infiltrated” the civil service and the military.

However the main casualty of Widodo’s desire to accommodate every party and group that contributed to re-election could be the ambitious economic reform agenda the president aims to implement – notably the president’s plan to attract new FDI, particularly in infrastructure, manufacturing, and e-commerce sectors.

The plan would have included an economic package to further reduce burdensome permits and regulations, a comprehensive tax reform scheme that would have significantly lowered Indonesia’s corporate income tax, and the enactment of an ‘omnibus’ labour law that would have strictly limited minimum wage rises and made Indonesian labour regulations more flexible.

Given the rivalries between different ministers within the cabinet, raising the prospect of bureaucratic infighting over conflicting interests among different ministries, it looks a tall order for such a cabinet to agree on consistent and coordinated policies in areas such as economic reform, trade and investment, higher education, not to mention address the impact of a rapidly-changing global economy.

Alexander R. Arifianto is a Research Fellow with the Indonesia Programme, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author.